The Monkey reviewed three plays on Broadway in the last year—Chaplin, Golden Boy and The Nance—giving each of them thumbs up to varying degrees. How did these productions fare in this morning's Tony nominations? Well, let's see:

Golden Boy received eight Tony nominations: Best Revival of a Play, Best Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role in a Play (Danny Burstein and Tony Shalhoub), Best Scenic Design of a Play (Michael Yeargan), Best Costume Design of a Play (Catherine Zuber), Best Lighting Design of a Play (Donald Holder) and Best Direction of a Play (Bartlett Sher)

The Nance received five nominations: Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role in a Play (Nathan Lane), Best Scenic Design of a Play (John Lee Beatty), Best Costume Design of a Play (Ann Roth), Best Lighting Design of a Play (Japhy Weideman) and Best Sound Design of a Play (Leon Rothenberg).

Chaplin received one nomination: Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role in a Musical (Rob McClure).

Congratulations all around. And me? I feel lucky just to have been invited. (Click on the highlighted links to read my original reviews.)

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Monday, April 29, 2013

The Mary Pickford Cocktail

We're on a Mary Pickford kick here at the Monkey, having taken in two Pickford silents at the AFI-Silver in the past week. And in her honor, we dug up a recipe for the Mary Pickford cocktail.

Allegedly invented for her on the spot by a bartender in Havana, the ingredients for the Mary Pickford are as follows:

1 1/2 oz light rum

1 oz pineapple juice

1/2 tsp maraschino liqueur

1/2 tsp grenadine syrup

Mix in a cocktail shaker with ice and shake until your arm falls off, 30 seconds at least, preferably longer. Strain and serve very cold in a chilled cocktail glass.

By the way, do not confuse maraschino liqueur with maraschino cherry juice. Different things. One is a clear, dry liqueur distilled from sour Marasca cherries, the other is a disgustingly sweet more-candy-than-fruit garnish that graces ice cream sodas and the like. (I've seen a recipe for the Mary Pickford that dispenses with the maraschino liqueur altogether—apparently few bars these days stock it due to its expense. Up to you.)

There's also something called a Mary Pickford Collins, which involves licorice-infused gin, lemon grass syrup, and a bunch of other stuff I don't have. We'll leave that for another time.

(Would you'd rather make a Douglas Fairbanks? Click here for the recipe.)

Postscript: This is my thousandth post as the Mythical Monkey.

Allegedly invented for her on the spot by a bartender in Havana, the ingredients for the Mary Pickford are as follows:

1 1/2 oz light rum

1 oz pineapple juice

1/2 tsp maraschino liqueur

1/2 tsp grenadine syrup

Mix in a cocktail shaker with ice and shake until your arm falls off, 30 seconds at least, preferably longer. Strain and serve very cold in a chilled cocktail glass.

By the way, do not confuse maraschino liqueur with maraschino cherry juice. Different things. One is a clear, dry liqueur distilled from sour Marasca cherries, the other is a disgustingly sweet more-candy-than-fruit garnish that graces ice cream sodas and the like. (I've seen a recipe for the Mary Pickford that dispenses with the maraschino liqueur altogether—apparently few bars these days stock it due to its expense. Up to you.)

There's also something called a Mary Pickford Collins, which involves licorice-infused gin, lemon grass syrup, and a bunch of other stuff I don't have. We'll leave that for another time.

(Would you'd rather make a Douglas Fairbanks? Click here for the recipe.)

Postscript: This is my thousandth post as the Mythical Monkey.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Mary Pickford: Dorothy Vernon Of Haddon Hall (1924)

At first blush, Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall is a radical departure for its star Mary Pickford.

Based on a popular novel by Charles Major, Dorothy Vernon is a lavish costume drama set during the conflict between Queen Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. Pickford plays the title character, a real-life aristocrat who for reasons history has not quite remembered managed to alienate both sides in the battle of royal succession. The film is full of court intrigue, murder plots, sword fights—in short, the sort of movie Pickford's husband Douglas Fairbanks might have made during this period.

But as the story develops, the Pickford we know and love quickly emerges. She plays an adult role for once, but an eighteen year old on the eve of an arranged marriage to a scheming cousin who wants to use the occasion to attract the presence of Elizabeth, whom he plans to murder in a plot to put Mary Stuart on the throne of England.

If you know your British history, you know Mary Stuart never sat upon the throne of England so I don't think it's a spoiler to say that the plucky, feisty, bonny Dorothy—the traits most typical of a Pickford character—saves the day. (For more background about Pickford, click here.)

She succeeds with the help of her true love, Sir John Manners, essayed by Pickford's brother-in-law, Allan Forrest. (The film was a real family affair, with Pickford's sister Lottie playing Dorothy's lady-in-waiting.) Forrest plays his part in the Douglas Fairbanks style, with lots of swashbuckling and leaping about, and even throwing his back and laughing uproariously, a patented Fairbanks move.

And therein lies the film's weakness—Forrest is no Douglas Fairbanks. That fact is made abundantly clear in his very first scene, a shot of his wide muscular back as a doctor attends to wounds received in battle. Forrest was, in fact, a quite slender lad, and the back is doubled by none other than Fairbanks himself, who was filming The Thief of Bagdad one set over. I couldn't help but wonder how much more fun the film would have been if Fairbanks had actually played the role of John Manners. Not only would the acting and swordplay have been better, but the outsized nature of his magnetic personality would have short-circuited the need for so much character exposition that bogs down the beginning of the film.

But, alas, Fairbanks and Pickford made only one movie together, the 1929 talkie, The Taming of the Shrew.

Still, a Pickford movie is primarily about Mary Pickford, and she does not disappoint. She had one of the most expressive faces of the silent era, and one of the most appealing personas. Throw in the wonderful costumes and Pickford's stunt work performed herself when her double was injured—including a particularly dangerous gallop up a three-foot wide stair to the top of a narrow stone wall—and you've got a pretty entertaining movie on your hands.

The film wasn't one of Pickford's blockbuster smashes upon its release in 1924, but it did turn a tidy profit and was a nice prestige release for Pickford's studio, United Artists.

A newly-restored 35 mm print of the film is playing now in a limited run in select cities. Film historian Christel Schmidt, author of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, will be touring with the film, as will Ben Model, who provides live musical accompaniment. If you get a chance to see it before it heads back to the archives at the Cinematheque Royale de Belgique, by all means, don't miss it.

Based on a popular novel by Charles Major, Dorothy Vernon is a lavish costume drama set during the conflict between Queen Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. Pickford plays the title character, a real-life aristocrat who for reasons history has not quite remembered managed to alienate both sides in the battle of royal succession. The film is full of court intrigue, murder plots, sword fights—in short, the sort of movie Pickford's husband Douglas Fairbanks might have made during this period.

But as the story develops, the Pickford we know and love quickly emerges. She plays an adult role for once, but an eighteen year old on the eve of an arranged marriage to a scheming cousin who wants to use the occasion to attract the presence of Elizabeth, whom he plans to murder in a plot to put Mary Stuart on the throne of England.

If you know your British history, you know Mary Stuart never sat upon the throne of England so I don't think it's a spoiler to say that the plucky, feisty, bonny Dorothy—the traits most typical of a Pickford character—saves the day. (For more background about Pickford, click here.)

She succeeds with the help of her true love, Sir John Manners, essayed by Pickford's brother-in-law, Allan Forrest. (The film was a real family affair, with Pickford's sister Lottie playing Dorothy's lady-in-waiting.) Forrest plays his part in the Douglas Fairbanks style, with lots of swashbuckling and leaping about, and even throwing his back and laughing uproariously, a patented Fairbanks move.

And therein lies the film's weakness—Forrest is no Douglas Fairbanks. That fact is made abundantly clear in his very first scene, a shot of his wide muscular back as a doctor attends to wounds received in battle. Forrest was, in fact, a quite slender lad, and the back is doubled by none other than Fairbanks himself, who was filming The Thief of Bagdad one set over. I couldn't help but wonder how much more fun the film would have been if Fairbanks had actually played the role of John Manners. Not only would the acting and swordplay have been better, but the outsized nature of his magnetic personality would have short-circuited the need for so much character exposition that bogs down the beginning of the film.

But, alas, Fairbanks and Pickford made only one movie together, the 1929 talkie, The Taming of the Shrew.

Still, a Pickford movie is primarily about Mary Pickford, and she does not disappoint. She had one of the most expressive faces of the silent era, and one of the most appealing personas. Throw in the wonderful costumes and Pickford's stunt work performed herself when her double was injured—including a particularly dangerous gallop up a three-foot wide stair to the top of a narrow stone wall—and you've got a pretty entertaining movie on your hands.

The film wasn't one of Pickford's blockbuster smashes upon its release in 1924, but it did turn a tidy profit and was a nice prestige release for Pickford's studio, United Artists.

A newly-restored 35 mm print of the film is playing now in a limited run in select cities. Film historian Christel Schmidt, author of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, will be touring with the film, as will Ben Model, who provides live musical accompaniment. If you get a chance to see it before it heads back to the archives at the Cinematheque Royale de Belgique, by all means, don't miss it.

Friday, April 26, 2013

Godspeed, George Jones

We here at the Monkey want to take time out to say goodbye to our old friend and neighbor, George Jones. Not only was he one of the greatest singer-songwriters in country music history, he livened up the neighborhood when I was a kid—which is always a plus in my book. Rest in peace, Mr. Jones.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

More Mary Pickford At The AFI-Silver

As part of its (hopefully) annual Silent Cinema Showcase, the AFI-Silver is showing the Mary Pickford film Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall this Friday, April 26, at 7:30 p.m.

Dorothy Vernon is a historical costume drama set during the conflict between Queen Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots—a real change of pace for Pickford. This heretofore difficult-to-see film is a 35 mm restoration print assembled from elements found in the Cinematheque Royale de Belgique and the Library of Congress.

Ben Model will provide live musical accompaniment.

I can't wait!

As an added bonus, Christel Schmidt, the author of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, will again speak, sign copies of her book and hang out after the show. I picked up my own copy of her book last Saturday and I can tell you, it's a steal at $36 (it lists for $45)—a five-pound coffee table-sized book filled not only with gorgeous photographs but also essays by Kevin Brownlow, Molly Haskell, Eileen Whitfield, Ms. Schmidt and many others. I have a feeling it's going to prove indispensable as I continue my own exploration of silent film.

I can testify (in court, if necessary) that Ms. Schmidt is smart, cool, redheaded and knows more about Mary Pickford than most people know about themselves. Come on down and meet her for yourself.

Don't live in the Silver Spring area? Pish posh! Two weeks ago, my brother and I drove 2800 miles in four days, covering the last 838 miles, from Madison, Wisconsin, to Baltimore, Maryland, in fourteen hours. And you've got a day and a half. Basically, nobody east of Kansas City has an excuse for missing this event.

Katie-Bar-The-Door and I promise to be there so be sure to say hello. We'll be easy enough to spot—we look just like ourselves!

Dorothy Vernon is a historical costume drama set during the conflict between Queen Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots—a real change of pace for Pickford. This heretofore difficult-to-see film is a 35 mm restoration print assembled from elements found in the Cinematheque Royale de Belgique and the Library of Congress.

Ben Model will provide live musical accompaniment.

I can't wait!

As an added bonus, Christel Schmidt, the author of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, will again speak, sign copies of her book and hang out after the show. I picked up my own copy of her book last Saturday and I can tell you, it's a steal at $36 (it lists for $45)—a five-pound coffee table-sized book filled not only with gorgeous photographs but also essays by Kevin Brownlow, Molly Haskell, Eileen Whitfield, Ms. Schmidt and many others. I have a feeling it's going to prove indispensable as I continue my own exploration of silent film.

I can testify (in court, if necessary) that Ms. Schmidt is smart, cool, redheaded and knows more about Mary Pickford than most people know about themselves. Come on down and meet her for yourself.

Don't live in the Silver Spring area? Pish posh! Two weeks ago, my brother and I drove 2800 miles in four days, covering the last 838 miles, from Madison, Wisconsin, to Baltimore, Maryland, in fourteen hours. And you've got a day and a half. Basically, nobody east of Kansas City has an excuse for missing this event.

Katie-Bar-The-Door and I promise to be there so be sure to say hello. We'll be easy enough to spot—we look just like ourselves!

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Almost Wasn't Wednesday #3: The Wizard Of Oz With Shirley Temple

For a dearly-beloved four-star classic, The Wizard of Oz was a troubled production, from start to finish.

The studio wanted Shirley Temple to star, couldn't get her, considered Deanna Durbin and Bonita Granville, then reluctantly settled for Judy Garland. W.C. Fields almost signed on to play the Wizard, but wanted a little too much money. Gale Sondergaard agreed to play a sexy Wicked Witch of the West then dropped out when the role changed, first in favor of Edna Mae Oliver then finally Margaret Hamilton. Buddy Ebsen, of course, began as the Tin Man before falling ill. Eddie Cantor was once upon a time considered for the Scarecrow. Fanny Brice and Beatrice Lillie were first choices for the Good Witch. And Leo, the MGM lion, was initially discussed as a possibility to play the Cowardly Lion before somebody came to their senses and cast Bert Lahr.

Even then, director Richard Thorpe was fired twelve days into filming—with good reason, it sounds like. He'd slapped a blonde wig and garish adult makeup on Judy Garland, and instead of an iconic yellow brick road, imagined round stepping stones instead. Jeepers! It took Victor Fleming to set the project right, and even then King Vidor filmed all the black-and-white scenes when Fleming left to rescue Gone With The Wind.

I've re-imagined the movie poster with maximum crapitude in mind (as always, click on the picture to see it full size). In the short run, The Wizard of Oz with Shirley Temple might have grossed more at the box office, but in the long run, I'm certain it would have been largely forgotten—when was the last time you watched her in The Blue Bird? Shirley, as great as she was, didn't have the musical chops to pull off "Over The Rainbow" or the range as an actress to capture the teenage angst Judy Garland brought to the role.

Neither does the notion of a sexy Witch work for me—Margaret Hamilton scared the bejabbers out of me as a kid and I think that's a very necessary element of this particular fairy tale, maybe of all fairy tales. Besides, Gale Sondergaard wasn't all that sexy to begin with.

And finally, though it was a brain his Scarecrow was seeking, Ray Bolger provided the film's heart. Can't imagine the movie without him.

Postscript: By the way, yesterday was Shirley Temple's birthday. And all I got her was this lousy poster.

The studio wanted Shirley Temple to star, couldn't get her, considered Deanna Durbin and Bonita Granville, then reluctantly settled for Judy Garland. W.C. Fields almost signed on to play the Wizard, but wanted a little too much money. Gale Sondergaard agreed to play a sexy Wicked Witch of the West then dropped out when the role changed, first in favor of Edna Mae Oliver then finally Margaret Hamilton. Buddy Ebsen, of course, began as the Tin Man before falling ill. Eddie Cantor was once upon a time considered for the Scarecrow. Fanny Brice and Beatrice Lillie were first choices for the Good Witch. And Leo, the MGM lion, was initially discussed as a possibility to play the Cowardly Lion before somebody came to their senses and cast Bert Lahr.

Even then, director Richard Thorpe was fired twelve days into filming—with good reason, it sounds like. He'd slapped a blonde wig and garish adult makeup on Judy Garland, and instead of an iconic yellow brick road, imagined round stepping stones instead. Jeepers! It took Victor Fleming to set the project right, and even then King Vidor filmed all the black-and-white scenes when Fleming left to rescue Gone With The Wind.

I've re-imagined the movie poster with maximum crapitude in mind (as always, click on the picture to see it full size). In the short run, The Wizard of Oz with Shirley Temple might have grossed more at the box office, but in the long run, I'm certain it would have been largely forgotten—when was the last time you watched her in The Blue Bird? Shirley, as great as she was, didn't have the musical chops to pull off "Over The Rainbow" or the range as an actress to capture the teenage angst Judy Garland brought to the role.

Neither does the notion of a sexy Witch work for me—Margaret Hamilton scared the bejabbers out of me as a kid and I think that's a very necessary element of this particular fairy tale, maybe of all fairy tales. Besides, Gale Sondergaard wasn't all that sexy to begin with.

And finally, though it was a brain his Scarecrow was seeking, Ray Bolger provided the film's heart. Can't imagine the movie without him.

Postscript: By the way, yesterday was Shirley Temple's birthday. And all I got her was this lousy poster.

Monday, April 22, 2013

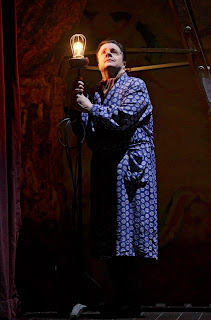

The Nance: Nathan Lane's Latest Broadway Triumph

Any review of a Broadway play starring Nathan Lane necessarily starts with Nathan Lane's performance, and when Nathan Lane's performance turns out to be one of the best of his career, your review can pretty much stop there, too.

That I start elsewhere and write five hundred words before getting to Nathan Lane—well, that's just what you've come to expect from the Mythical Monkey.

Set in 1937, The Nance recreates the "naughty, raucous" world of American burlesque in its lowbrow heyday just before its abrupt and unceremonious demise. A form of variety show popular in America from the 1860s to the early 1940s, burlesque featured songs, crude humor and striptease—with the striptease distinguishing it from vaudeville, music hall and "legitimate" theater. In terms of respectability, burlesque was the lowest of the low, but it gave us Sally Rand and Gypsy Rose Lee, and provided starts for Mae West, W.C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, Jackie Gleason, Red Skelton, and many others.

It may be a limited world, but in it, nobody is better at making people laugh than Chauncey Miles—two-time Tony winner Nathan Lane in top form—a stage comedian who specializes in what was known as a "nance" act, an exaggeratedly camp gay character who served up ribald comedy and broad double entendres while at the same time serving as an object of the audience's derision and merriment.

That off-stage Chauncey is a closeted gay man makes him something of a crying-on-the-inside kind of clown. Indeed, Chauncey specifically likens himself to Bert Williams, the real-life African-American comedian who performed in blackface, and in a moment perhaps a bit on the nose, quotes W.C. Fields who called Williams "the funniest man I've ever seen—and the saddest man I've ever known."

The contrast between Chauncey's on-stage joy and his off-stage misery is the source of much of the play's drama.

Yet while homosexuality in 1937 is a crime, and meeting like-minded men is difficult and dangerous, a sort of shadow society has evolved, with carefully-observed rules and rituals summed up by the recurring punchline "I'll meet you 'round the corner in a half an hour." The cops make occasional sweeps of known gay haunts, and gay-baiting thugs work out their insecurities and repressed desires with their fists, but in the main, "respectable" society and its gay counterpart have reached a don't ask-don't tell arrangement for co-existing.

And as he does in the theater, Chauncey thrives in this deeply-compromised environment. He lives not so much for the meeting at the beginning of the ritual or the sex at the end, as for the thirty minutes in between, a half hour of exquisite anticipation that could end in a beating, an arrest, a trip to the moon on gossamer wings or even nothing at all.

Then two developments threaten Chauncey's carefully-disordered world—monogamy, in the form of a young man (Jonny Orsini), and unemployment, in the form of government censorship.

The difficulty of the former for someone addicted to the chase, you probably intuitively grasp. The latter was the work of Fiorello LaGuardia, the mayor of New York from 1937 to 1945. Although never appearing on stage, LaGuardia's impact on the story is as outsized as his impact on the city he governed. A reform-minded Republican, he supported FDR and the New Deal, cracked down on government corruption, and championed the rights of immigrants and minorities. He was also authoritarian, self-aggrandizing and priggish in the extreme, and he made it his mission to shut down the burlesque houses that were popular in New York at the time.

As his legal and professional status deteriorates, Chauncey falls back on old patterns. The old life is as risky and unsatisfying as ever, but it's also familiar, reminding us that even unhappiness can provide a measure of comfort if it's what you've know best.

That Nathan Lane can serve up so many genuine laughs while convincingly playing such a tortured (and in many ways, unlikeable) character is a testament to his real versatility as an actor. He doesn't soften Chauncey one bit, yet you feel for him. Nor does he shy away from the offensive nature of "nance" humor, yet you can't help but laugh with him.

I wonder how many reviewers have predicted that Lane's performance will earn him another Tony nomination—probably all of them—but in this case, I'd be shirking my duty if I failed to state the obvious.

Still, I'm going to be frank with you—The Nance is not for everybody, especially if the everybody in your group includes a homophobic out-of-towner and his blue-nosed great aunt. The production, directed by three-time Tony winner Jack O'Brien, features full frontal male nudity, exotic dancers in g-strings and pasties, and enough double (and single) entendres to fill out a drag queen's stage act.

Too, playwright Douglas Carter Beane tries a bit too hard to cover every base, touching not just on Chauncey's professional and personal problems, but also on union politics, right-wing hypocrisy, left-wing cowardice, New York parochialism, and a host of other issues. I mean, let's face it, when you introduce a Marxist-spouting stripper to the proceedings—and not for laughs—you're gilding the lily.

But all in all, these are minor quibbles. The point of the evening is Nathan Lane. And Nathan Lane is terrific.

The Nance is currently playing at the Lyceum Theatre in New York.

That I start elsewhere and write five hundred words before getting to Nathan Lane—well, that's just what you've come to expect from the Mythical Monkey.

Set in 1937, The Nance recreates the "naughty, raucous" world of American burlesque in its lowbrow heyday just before its abrupt and unceremonious demise. A form of variety show popular in America from the 1860s to the early 1940s, burlesque featured songs, crude humor and striptease—with the striptease distinguishing it from vaudeville, music hall and "legitimate" theater. In terms of respectability, burlesque was the lowest of the low, but it gave us Sally Rand and Gypsy Rose Lee, and provided starts for Mae West, W.C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, Jackie Gleason, Red Skelton, and many others.

It may be a limited world, but in it, nobody is better at making people laugh than Chauncey Miles—two-time Tony winner Nathan Lane in top form—a stage comedian who specializes in what was known as a "nance" act, an exaggeratedly camp gay character who served up ribald comedy and broad double entendres while at the same time serving as an object of the audience's derision and merriment.

That off-stage Chauncey is a closeted gay man makes him something of a crying-on-the-inside kind of clown. Indeed, Chauncey specifically likens himself to Bert Williams, the real-life African-American comedian who performed in blackface, and in a moment perhaps a bit on the nose, quotes W.C. Fields who called Williams "the funniest man I've ever seen—and the saddest man I've ever known."

The contrast between Chauncey's on-stage joy and his off-stage misery is the source of much of the play's drama.

Yet while homosexuality in 1937 is a crime, and meeting like-minded men is difficult and dangerous, a sort of shadow society has evolved, with carefully-observed rules and rituals summed up by the recurring punchline "I'll meet you 'round the corner in a half an hour." The cops make occasional sweeps of known gay haunts, and gay-baiting thugs work out their insecurities and repressed desires with their fists, but in the main, "respectable" society and its gay counterpart have reached a don't ask-don't tell arrangement for co-existing.

And as he does in the theater, Chauncey thrives in this deeply-compromised environment. He lives not so much for the meeting at the beginning of the ritual or the sex at the end, as for the thirty minutes in between, a half hour of exquisite anticipation that could end in a beating, an arrest, a trip to the moon on gossamer wings or even nothing at all.

Then two developments threaten Chauncey's carefully-disordered world—monogamy, in the form of a young man (Jonny Orsini), and unemployment, in the form of government censorship.

The difficulty of the former for someone addicted to the chase, you probably intuitively grasp. The latter was the work of Fiorello LaGuardia, the mayor of New York from 1937 to 1945. Although never appearing on stage, LaGuardia's impact on the story is as outsized as his impact on the city he governed. A reform-minded Republican, he supported FDR and the New Deal, cracked down on government corruption, and championed the rights of immigrants and minorities. He was also authoritarian, self-aggrandizing and priggish in the extreme, and he made it his mission to shut down the burlesque houses that were popular in New York at the time.

As his legal and professional status deteriorates, Chauncey falls back on old patterns. The old life is as risky and unsatisfying as ever, but it's also familiar, reminding us that even unhappiness can provide a measure of comfort if it's what you've know best.

That Nathan Lane can serve up so many genuine laughs while convincingly playing such a tortured (and in many ways, unlikeable) character is a testament to his real versatility as an actor. He doesn't soften Chauncey one bit, yet you feel for him. Nor does he shy away from the offensive nature of "nance" humor, yet you can't help but laugh with him.

I wonder how many reviewers have predicted that Lane's performance will earn him another Tony nomination—probably all of them—but in this case, I'd be shirking my duty if I failed to state the obvious.

Still, I'm going to be frank with you—The Nance is not for everybody, especially if the everybody in your group includes a homophobic out-of-towner and his blue-nosed great aunt. The production, directed by three-time Tony winner Jack O'Brien, features full frontal male nudity, exotic dancers in g-strings and pasties, and enough double (and single) entendres to fill out a drag queen's stage act.

Too, playwright Douglas Carter Beane tries a bit too hard to cover every base, touching not just on Chauncey's professional and personal problems, but also on union politics, right-wing hypocrisy, left-wing cowardice, New York parochialism, and a host of other issues. I mean, let's face it, when you introduce a Marxist-spouting stripper to the proceedings—and not for laughs—you're gilding the lily.

But all in all, these are minor quibbles. The point of the evening is Nathan Lane. And Nathan Lane is terrific.

The Nance is currently playing at the Lyceum Theatre in New York.

Sunday, April 21, 2013

New Print Of Harold Lloyd's Safety Last! Tonight At The AFI-Silver

Yesterday was Harold Lloyd's 120th birthday—and I didn't get him a thing!

This evening at 7:30 p.m., though, the AFI-Silver is showing a brand new 35mm print of his comedy classic Safety Last!, and after the rousing success of yesterday's showing of Mary Pickford's Sparrows, Katie-Bar-The-Door and I have decided to venture out. The presentation will feature live musical accompaniment by Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton.

In a great theater with live music isn't the only way to see a silent movie, but it is the best. If you've never seen a silent film, this is a good one to start with. If you have, well, then what are you waiting for? Come on down and join us.

This evening at 7:30 p.m., though, the AFI-Silver is showing a brand new 35mm print of his comedy classic Safety Last!, and after the rousing success of yesterday's showing of Mary Pickford's Sparrows, Katie-Bar-The-Door and I have decided to venture out. The presentation will feature live musical accompaniment by Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton.

In a great theater with live music isn't the only way to see a silent movie, but it is the best. If you've never seen a silent film, this is a good one to start with. If you have, well, then what are you waiting for? Come on down and join us.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Mary Pickford At The AFI Silver On Saturday

If you've been following my blog for any length of time, you know I'm a big fan of Mary Pickford and have written about her many times (e.g., here, here, here and here).

As part of its Silent Cinema Showcase, running from April 20 - May 4, the American Film Institute will be showing the 1926 Mary Pickford film Sparrows on Saturday, April 20, 2013, at its AFI Silver theater in Silver Spring, Maryland. The film will be presented with live musical accompaniment and begins promptly at 2 p.m.

In addition, film historian Christel Schmidt will be signing copies of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, a collection of essays about the woman who, as I have written, is "pound for pound the most powerful woman in Hollywood history." The Monkey plans to be there, although I'm not sure whether I'll ask for Ms. Schmidt's autograph. Some people are a bit put off meeting a blog-typing sock monkey—maybe it's the fluffy stuffing, maybe it's the buttons for eyes.

Definitely will be buying the book, though. See you there.

As part of its Silent Cinema Showcase, running from April 20 - May 4, the American Film Institute will be showing the 1926 Mary Pickford film Sparrows on Saturday, April 20, 2013, at its AFI Silver theater in Silver Spring, Maryland. The film will be presented with live musical accompaniment and begins promptly at 2 p.m.

In addition, film historian Christel Schmidt will be signing copies of Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, a collection of essays about the woman who, as I have written, is "pound for pound the most powerful woman in Hollywood history." The Monkey plans to be there, although I'm not sure whether I'll ask for Ms. Schmidt's autograph. Some people are a bit put off meeting a blog-typing sock monkey—maybe it's the fluffy stuffing, maybe it's the buttons for eyes.

Definitely will be buying the book, though. See you there.

Wednesday, April 17, 2013

Almost Wasn't Wednesday #2: The Philadelphia Story With Clark Gable And Spencer Tracy

If you're reading this blog, I assume you know the sophisticated comedy classic, The Philadelphia Story. Designed as a comeback vehicle for Katharine Hepburn, the movie won two Oscars (Jimmy Stewart as best actor, and best screenplay) and features what many consider the best performance of Cary Grant's illustrious career.

But if Hepburn had had her way, the movie would have starred not Grant and Stewart but Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy. That's right—Hepburn, who owned the film rights, wanted Gable and Tracy, and if they hadn't been tied up with other projects, that's who the studio would have cast.

And in the context of the times, you can see where she was coming from. Gable was the most popular actor in Hollywood, fresh off the smashing success of Gone With The Wind. And he'd made a career of taking the mickey out of upper class actresses—his Oscar-winning turn across from Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night, in the aforementioned Gone With The Wind with Vivien Leigh, and many others.

As for Tracy, he'd won two Oscars, and Hepburn's instincts that she and he would be good together was right on the money—they eventually made nine movies together, including such comedy classics as Woman of the Year, Adam's Rib and Pat and Mike.

Not to mention Grant and Stewart weren't necessarily sure things in early 1940. We look back on Hepburn's three previous films with Grant as being treasures, particularly Bringing Up Baby and Holiday, but the fact is, all their previous pairings had been flops at the box office—indeed, the colossal failure of the former is why Hepburn needed a comeback vehicle in the first place.

And while Stewart had earned an Oscar-nomination the previous year with Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, nobody was ready yet to put him on the Mt. Rushmore of acting.

But sometimes, not getting what you want is the best thing that can happen to you. While I'm certain The Philadelphia Story would have been a hit with Gable and Tracy, it would have lacked Grant's champagne fizz and Stewart's fevered act-three naivete. You don't tug on Superman's cape, you don't spit into the wind, and you don't mess with a movie that film guru Leslie Halliwell called "Hollywood's most wise and sparkling comedy."

Bonus Trivia: On Broadway, Joseph Cotten and Van Heflin played the Grant and Stewart roles, respectively.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Chaplin At 124

In honor of his birthday today, here's a portion of my most popular post about Charlie Chaplin.

"I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time."—Buster Keaton, in a 1960 interview with Herbert Feinstein

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After Chaplin's contract at Essanay expired, he signed with the Mutual Film Corporation to direct and star in a dozen two-reel comedies—known colloquially as "the Chaplin Mutuals"—for the then-unheard of sum of $670,000, the most any entertainer had been paid in history. "Next to the war in Europe," a Mutual publicist wrote, "Chaplin is the most expensive item in contemporaneous history." The deal with Mutual afforded Chaplin two luxuries he'd never had before as a director—time and money—and he took full advantage of the opportunity, not only re-shooting sequences that didn't match his vision, but also experimenting with the comedic form itself.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

As his leading lady, Chaplin brought Edna Purviance with him from Essanay. Purviance (Purr-VYE-ance) had been working as a stenographer in San Francisco when she caught Chaplin's eye, who, either as a trite come-on or because he could more easily mold the novice actress to fit his ideas of comedy, asked her if she would like to be in pictures. "I laughed at the idea," she said later, "but agreed to try it."

Although their romantic relationship was brief, Purviance continued to play Chaplin's leading lady for nine years, appearing in approximately forty films (the exact number is in dispute), more than any other actress.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Each film is a loose collection of well-polished comic set-ups and payoffs, distinguishable from Chaplin's work at Keystone and Essanay only be the quality of their gags.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

Chaplin returned to form with his next film, One A.M., which combined elements from a pair of Max Linder "drunk comedies," First Cigar and Max Takes Tonics, to create a one-man tour de force that plays a little like a wager that a single joke—a drunk fumbling his way up a flight of stairs to bed—can work for twenty uninterrupted minutes.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

As in most of his films, the camera work is spare, the editing unobtrusive, with both focused on featuring the best available performance rather than solving technical problems such as continuity or matching edits. Like Fred Astaire, who insisted his dances be filmed in an uninterrupted take with an angle wide and long enough to show the performance from head to toe, Chaplin mostly used long shots and uninterrupted takes to show his audience that the dance-like rhythm of his intricate physical gags are not cheats conjured up in the editing room, but reflect his real abilities. Anyway, I'm no fan of fancy camera work that exists only to prove the director wasn't napping during that day's lecture at film school and though Chaplin's style remained primitive compared to his contemporaries, it was a conscious choice with a specific payoff in mind.

Chaplin finished out 1916 with four films—The Count, The Pawnshop, Behind The Screen and The Rink—that returned to familiar formulas, but the comedy was well thought out, as funny as anything he had ever done. Of the four, I'd rate The Pawnshop and especially Behind The Screen the most highly. In the former watch particularly for the Tramp's efforts to evaluate the alarm clock Albert Austin has brought into the shop to pawn—do I need to tell you how things work out for Austin and the clock?

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

Chaplin opened 1917 with one of the most beloved comedies of his career, Easy Street. Set in the slums of New York, the Tramp wanders into a Salvation Army style mission and falls instantly in love with the pianist (Edna Purviance, of course). Determined to redeem himself in her eyes, the Tramp volunteers for a job as a policeman with a beat on the notorious Easy Street (which is anything but). The Tramp's battles with the local bully—Campbell, who is a foot taller and a foot wider than Chaplin—provides the bulk of the comedy.

Easy Street is particularly harsh, populated with drug addicts, rapists, wife beaters, and hungry children, the sort of neighborhood Chaplin himself grew up in as the son of an alcoholic father and mentally-ill mother, yet the finished film is pure laughs and I never feel like Chaplin is lecturing or hectoring us.

He would return to this setting in 1921 for his first feature-length film, The Kid.

Typical of the Mutual era, Chaplin followed the personal with the formulaic, this time with The Cure, another drunk act reminiscent of One A.M. except this time with a sanitarium full of rich hypochondriacs instead of furniture to trip over. Again, Chaplin takes simple jokes, such as a man caught in a revolving door, and stretches them to unbelievable lengths, repeating them, adding new elements, changing payoffs. In one scene, Chaplin—here playing a rich alcoholic rather than the Tramp—attempts to drink from the health-giving spring that is the facility's main attraction, yet always winds up filling up his hat instead. Later, though, after the stash of booze he's smuggled in to tide him over during rehab winds up in the well, he of course doesn't spill a drop.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

Chaplin's next film, The Immigrant, his eleventh at Mutual, is not the funniest, but I would argue it was the most important—maybe the single most important development in movie comedy from any source to that time.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

In a short chock full of comedy, Chaplin managed to show the hardship's immigrants faced as they tried to reach America—intolerable shipboard conditions including overcrowding, theft, execrable food, illness; the humiliation of being herded like cattle through Ellis Island; and finally, after landing in New York, the linguistic, economic and cultural hurdles, as well as nativist hostility, involved in adapting to every day life in a foreign country, demonstrated in this case through an act as simple as ordering dinner in a restaurant.

Yet Chaplin also captures the hope and promise that America at that time represented to millions worldwide. The scene of hopeful passengers crowding the deck to watch in silence as the ship sails past the Statue of Liberty is justly one of the most famous of the silent era. And the giddiness with which the Tramp courts the Girl (Purviance) is a perfect expression of the indomitable human will to survive.

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

If he wasn't already, Chaplin's Tramp was from this point forward identified with those first-generation immigrants then making up more than ten percent of America's population, as well as with those abroad who yearned to breathe free.

"The Immigrant," Chaplin said years later, "touched me more than any other film I made."

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

The Immigrant is preserved in the National Film Registry.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

After Mutual, Chaplin scored his first million dollar payday, signing with First National, a association of independent theater owners seeking a cut of the lucrative film distribution pie. Under the terms of the contract, Chaplin was to direct eight two-reel comedies, but the twenty minute format could not longer satisfy his artistic ambitions. Before his deal with First National was done, Chaplin had directed, among other things, his first feature length film, The Kid, as well as the four-reel war comedy, Shoulder Arms.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

Despite reaching ever more dizzying heights of fame, fortune and artistic achievement, Chaplin later confessed his years at Mutual were the happiest of his life. "I was light and unencumbered," he wrote, "twenty-seven years old, with fabulous prospects and a friendly, glamorous world before me."

Years later, Chaplin's son Sydney found himself at the Silent Movie Theater in Hollywood enjoying a revival of Chaplin's Mutuals only to be out-laughed by an elderly gentleman a few rows behind him. Turning to investigate he discovered "[i]t was my father who was laughing the loudest! Tears were rolling down his cheeks from laughing so hard and he had to wipe his eyes with his handkerchief."

"Perhaps," wrote Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance, "[Chaplin] had great fondness for the Mutuals simply for the same reason that generations of audiences have as well—because of the sheer joy, comic inventiveness, and hilarity of this extraordinary series of films."

"I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time."—Buster Keaton, in a 1960 interview with Herbert Feinstein

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.

After his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios in 1914, Chaplin signed a one-year deal with Essanay Studios where he directed fourteen shorts, including such films as The Tramp and Burlesque On Carmen. By the end of that year, Chaplin was the most famous entertainer in the world, and seeing his work in the context of its times, it's clear to me now he was to film comedy what D.W. Griffith was to film drama, establishing the rules and raising the bar.After Chaplin's contract at Essanay expired, he signed with the Mutual Film Corporation to direct and star in a dozen two-reel comedies—known colloquially as "the Chaplin Mutuals"—for the then-unheard of sum of $670,000, the most any entertainer had been paid in history. "Next to the war in Europe," a Mutual publicist wrote, "Chaplin is the most expensive item in contemporaneous history." The deal with Mutual afforded Chaplin two luxuries he'd never had before as a director—time and money—and he took full advantage of the opportunity, not only re-shooting sequences that didn't match his vision, but also experimenting with the comedic form itself.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals.

In support of this new venture, Chaplin gathered around him a team of familiar faces, recruiting a couple of friends from his days with the British music hall troupe. At 6'5" and 300 pounds, Eric Campbell was the most prominent of Chaplin's supporting players; a full foot taller and 175 pounds heavier than Chaplin, he made a good comic foil for the Tramp, and wound up playing his nemesis in eleven of the twelve Mutuals. And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics.

And wearing the ridiculously fake brush moustache known as a soup strainer was Albert Austin who performed mostly as the straight man on the receiving end of the Tramp's more destructive antics. As his leading lady, Chaplin brought Edna Purviance with him from Essanay. Purviance (Purr-VYE-ance) had been working as a stenographer in San Francisco when she caught Chaplin's eye, who, either as a trite come-on or because he could more easily mold the novice actress to fit his ideas of comedy, asked her if she would like to be in pictures. "I laughed at the idea," she said later, "but agreed to try it."

Although their romantic relationship was brief, Purviance continued to play Chaplin's leading lady for nine years, appearing in approximately forty films (the exact number is in dispute), more than any other actress.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.

Chaplin began his career at Mutual in the spring of 1916 with a couple of formula comedies, The Floorwalker and The Fireman. In the former, the Tramp wanders into a department store and wreaks havoc—knocking over displays, playing hide and seek with detectives, trashing the wares—before trading places with a look-alike store manager (future director Lloyd Bacon) who unbeknownst to the Tramp has just embezzled the payroll. In the latter, Chaplin plays the world's laziest firefighter—the kind of guy who stuffs a rag in the alarm bell to keep it from ringing—but comes to the rescue of a pretty girl (Purviance) when a fire breaks out.Each film is a loose collection of well-polished comic set-ups and payoffs, distinguishable from Chaplin's work at Keystone and Essanay only be the quality of their gags.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love.

Chaplin's third film at Mutual, The Vagabond, starts with a typical slapstick set-up—the Tramp as traveling musician busking in a bar for handouts—but quickly turns into the stuff of Victorian melodrama with the story of a wealthy middle aged woman haunted by the memory of a kidnapped child converging in a series of coincidences worthy of Charles Dickens with the story of young woman (Purviance) held captive by a band of gypsies. Into that mix, Chaplin introduced several themes that would characterize his work forever after—the separation of parent from child, artistic insecurity, noble self-sacrifice, and especially the exquisite pain of unrequited love. The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.

The attempt to wed slapstick to the dramatic form made The Vagabond Chaplin's most ambitious film to date, but result was the most disappointing. There's nothing wrong with sentimentality per se—The Kid, for example, was one of the era's best films—and viewed objectively, from the outside looking in, the Tramp's white knight complex can be hilarious (see, e.g., The Pawnshop, where an old con's tale leaves Chaplin sobbing), but here, having indulged his own insecurities simply as the default mode for a situation he hasn't fully worked out, the result is not moving but mawkish, and I imagine that those who complain that Chaplin is too sentimental for their tastes are really saying he too often fails to establish an emotional connection to the characters that would justify the Tramp's (and our) tears.Chaplin returned to form with his next film, One A.M., which combined elements from a pair of Max Linder "drunk comedies," First Cigar and Max Takes Tonics, to create a one-man tour de force that plays a little like a wager that a single joke—a drunk fumbling his way up a flight of stairs to bed—can work for twenty uninterrupted minutes.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.

Chaplin plays variations on the gag the way a jazz virtuoso plays variations on a theme, building simple movements into complex ones, anticipating some payoffs, denying others, going off in unexpected directions, finally returning to the beginning and starting something new.As in most of his films, the camera work is spare, the editing unobtrusive, with both focused on featuring the best available performance rather than solving technical problems such as continuity or matching edits. Like Fred Astaire, who insisted his dances be filmed in an uninterrupted take with an angle wide and long enough to show the performance from head to toe, Chaplin mostly used long shots and uninterrupted takes to show his audience that the dance-like rhythm of his intricate physical gags are not cheats conjured up in the editing room, but reflect his real abilities. Anyway, I'm no fan of fancy camera work that exists only to prove the director wasn't napping during that day's lecture at film school and though Chaplin's style remained primitive compared to his contemporaries, it was a conscious choice with a specific payoff in mind.

Chaplin finished out 1916 with four films—The Count, The Pawnshop, Behind The Screen and The Rink—that returned to familiar formulas, but the comedy was well thought out, as funny as anything he had ever done. Of the four, I'd rate The Pawnshop and especially Behind The Screen the most highly. In the former watch particularly for the Tramp's efforts to evaluate the alarm clock Albert Austin has brought into the shop to pawn—do I need to tell you how things work out for Austin and the clock?

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.

The latter, the story of a much put-upon worker bee (Chaplin) in a studio full of lazy, incompetent bosses, was aimed squarely at Mack Sennett who was happy to spend the millions Chaplin generated for Keystone Studios while paying his star a pittance ($125 a week with a $25 bonus for each film he directed). Chaplin had mined a similar vein at Essanay with His First Job, also about the Tramp taking a job at a movie studio, but the barbs here are sharper, the comedy funnier.Chaplin opened 1917 with one of the most beloved comedies of his career, Easy Street. Set in the slums of New York, the Tramp wanders into a Salvation Army style mission and falls instantly in love with the pianist (Edna Purviance, of course). Determined to redeem himself in her eyes, the Tramp volunteers for a job as a policeman with a beat on the notorious Easy Street (which is anything but). The Tramp's battles with the local bully—Campbell, who is a foot taller and a foot wider than Chaplin—provides the bulk of the comedy.

He would return to this setting in 1921 for his first feature-length film, The Kid.

Typical of the Mutual era, Chaplin followed the personal with the formulaic, this time with The Cure, another drunk act reminiscent of One A.M. except this time with a sanitarium full of rich hypochondriacs instead of furniture to trip over. Again, Chaplin takes simple jokes, such as a man caught in a revolving door, and stretches them to unbelievable lengths, repeating them, adding new elements, changing payoffs. In one scene, Chaplin—here playing a rich alcoholic rather than the Tramp—attempts to drink from the health-giving spring that is the facility's main attraction, yet always winds up filling up his hat instead. Later, though, after the stash of booze he's smuggled in to tide him over during rehab winds up in the well, he of course doesn't spill a drop.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.

The film's structure is loose, and the basic plot is a staple of Chaplin's comedy dating back at least to The Rounders in 1914, but with time to work through his ideas, the individual pieces are polished gems.Chaplin's next film, The Immigrant, his eleventh at Mutual, is not the funniest, but I would argue it was the most important—maybe the single most important development in movie comedy from any source to that time.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.

The Immigrant is the story of the Tramp's journey from Europe to America, starting in medias res on board an overcrowded ship and ending on the streets of New York. In the twenty minutes in between, Chaplin better captured the immigrant experience than all the "serious" films before or since, and in doing so succeeded at last in wedding the slapstick form to a dramatic subject.In a short chock full of comedy, Chaplin managed to show the hardship's immigrants faced as they tried to reach America—intolerable shipboard conditions including overcrowding, theft, execrable food, illness; the humiliation of being herded like cattle through Ellis Island; and finally, after landing in New York, the linguistic, economic and cultural hurdles, as well as nativist hostility, involved in adapting to every day life in a foreign country, demonstrated in this case through an act as simple as ordering dinner in a restaurant.

Yet Chaplin also captures the hope and promise that America at that time represented to millions worldwide. The scene of hopeful passengers crowding the deck to watch in silence as the ship sails past the Statue of Liberty is justly one of the most famous of the silent era. And the giddiness with which the Tramp courts the Girl (Purviance) is a perfect expression of the indomitable human will to survive.

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."

The Immigrant underscores the source of the Tramp's lasting appeal—the ability to handle even the most difficult situation with aplomb, a skill his audience no doubt envied as they met their daily suffering. As I once wrote in describing the most famous scene of Chaplin's 1925 triumph, The Gold Rush, "Oh, to relish the taste of the boot you've boiled for your Thanksgiving dinner the way the Tramp did—there's Chaplin's appeal reduced to a single scene."If he wasn't already, Chaplin's Tramp was from this point forward identified with those first-generation immigrants then making up more than ten percent of America's population, as well as with those abroad who yearned to breathe free.

"The Immigrant," Chaplin said years later, "touched me more than any other film I made."

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.

We take for granted now that film comedy can have a serious point to make, ala Dr. Strangelove or The Apartment, but that idea was still radical in an era when, as Roscoe Arbuckle explained to Buster Keaton while making their first film together, comedy was aimed at twelve year olds. The notion that comedy could offer up more than laughs comes largely from Chaplin.The Immigrant is preserved in the National Film Registry.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.

Chaplin finished his contract at Mutual with a crowd-pleasing throwback to his earlier comedies. The Adventurer is the story of an escaped convict (Chaplin) who worms his way into the affections of a high society debutante (Purviance) only to discover that her dad is the judge who sent him up. Lowlifes wreaking havoc with the carefully-ordered lives of the aristocracy was a staple of slapstick comedy almost from the origins of film itself, and would later become the meat of such acts as the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. In that sense, The Adventurer isn't particularly original; it is funny, though, one of the best of the bunch, and with it, Chaplin left Mutual giving his employers and his audience their money's worth.After Mutual, Chaplin scored his first million dollar payday, signing with First National, a association of independent theater owners seeking a cut of the lucrative film distribution pie. Under the terms of the contract, Chaplin was to direct eight two-reel comedies, but the twenty minute format could not longer satisfy his artistic ambitions. Before his deal with First National was done, Chaplin had directed, among other things, his first feature length film, The Kid, as well as the four-reel war comedy, Shoulder Arms.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.

In 1919, Chaplin would co-found his own distribution company, United Artists, teaming up with three of the greatest names of the silent era, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith.Despite reaching ever more dizzying heights of fame, fortune and artistic achievement, Chaplin later confessed his years at Mutual were the happiest of his life. "I was light and unencumbered," he wrote, "twenty-seven years old, with fabulous prospects and a friendly, glamorous world before me."

Years later, Chaplin's son Sydney found himself at the Silent Movie Theater in Hollywood enjoying a revival of Chaplin's Mutuals only to be out-laughed by an elderly gentleman a few rows behind him. Turning to investigate he discovered "[i]t was my father who was laughing the loudest! Tears were rolling down his cheeks from laughing so hard and he had to wipe his eyes with his handkerchief."

"Perhaps," wrote Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance, "[Chaplin] had great fondness for the Mutuals simply for the same reason that generations of audiences have as well—because of the sheer joy, comic inventiveness, and hilarity of this extraordinary series of films."

Friday, April 12, 2013

Catching Up—The Liebster Blog Award

While my brother and I were on the road from Seattle to Baltimore last week, Andrew D. of 1001 Movies I (Apparently) MUST See Before I Die blessed me with the Liebster Blog Award.

Thank you, Andrew!

I've been following Andrew's blog for quite a while now—since 2009, he's been watching his way through Stephen Jay Schneider's bossy tome 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, and writing his own reviews of these don't-expire-without-having-seen-them classics. Quite a project.

Anyway, the Liebster Blog Award has over the years become something of a project in and of itself—now requiring the recipient to divulge eleven random facts about him- or herself, answer eleven questions, make up eleven more questions and choose eleven more worthy winners. Jeepers! Somebody must have been a fan of This is Spinal Tap—everything goes up to eleven.

It's too much, really, and three is a much more pleasant number anyway, I think. So I hereby decree that from now on thou shall count to three, no more, no less. Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three. Four shalt thou not count, neither count thou two excepting that thou then proceed to three. Five is right out!

Three random facts gleaned from my trip across America:

1. I meticulously researched every aspect of the drive from Seattle to Baltimore—routes, hotels, restaurants, sites of interest—yet somehow forgot to note the departure time of my flight out, arriving at the airport only minutes before the plane took off.

2. Mt. Rushmore is even more spectacular than advertised. Also, if George Washington's nose is twenty-one feet long, can you imagine how much Martha Washington must have enjoyed the rest of him—the father of our country indeed!

3. Wall Drug—which, if you've ever driven through that part of the country you have no doubt heard of—is so chock full floor to ceiling with cheap souvenirs, it is, as my brother put it, like being trapped in the bottom of an arcade claw machine.

And now to answer three of the eleven questions from Andrew D.:

6. You're going to be stranded on a deserted island and can take along five movies...what are they?