By 1929, silent movies were as dead as disco and even the biggest stars of that suddenly bygone era found themselves struggling to connect with audiences eager for the next big thing.

Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks were no exception. Although they had enjoyed an unbroken string of box office hits dating back more than a decade—Pickford even had an Oscar on the mantle—Hollywood's first power couple faced the necessity of reinventing themselves as stars of the newfangled "all-talking" pictures.

It was an uphill battle all the way.

As I've written before, talkies were essentially a different medium from the silent movies that preceded them, related in the way that, say, poems and novels are related, but in the end requiring very different methods and skill sets, grounding pictures in an unforgiving reality, minimizing what were once strengths and revealing previously irrelevant limitations. John Gilbert was no longer a mythic lover but an ordinary man spouting cliched gibberish. Harold Lloyd no longer floated effortlessly up the sides of buildings but groaned and grunted as all too real bone and sinew waged a war against pitiless gravity. And Pickford and Fairbanks, who had made fortunes playing, respectively, tweener ingenues and swashbuckling supermen, suddenly became a middle-aged couple groping, like everybody else, for a way forward.

The different paths Fairbanks and Pickford chose at this point say a lot about what they thought about themselves and their careers.

Fairbanks, perhaps more than anyone in Hollywood history, loved being a star, and he loved playing the parts that had made him one. Though he was too old to swashbuckle anymore, he chose to continue playing exuberant, over-the-top men of action, essentially offering his fans what he had always given them, only now with sound.

Pickford, on the other hand, was determined to chart a new course, bobbing her hair and playing a tragic flapper in her first talking picture, Coquette. "I'm sick of Cinderella parts," she said, "of wearing rags and tatters. I want to wear smart clothes and play the lover."

Although Coquette succeeded in luring a curious public into theaters and won Pickford an Oscar—after she campaigned her heart out for it—the film hadn't placated the star's old fans or won her any new ones, and her future was still very much up in the air.

For her next picture—Fairbanks's talkie debut—Pickford chose The Taming of the Shrew, the Shakespearean comedy about a marriageable young man in search of a rich bride, even one as sharp tongued as Kate Minola. The picture boasted at least two firsts: it was the first all-talking version of a Shakespeare play, and it was the first time (not counting cameos and promotional shorts) that Fairbanks and Pickford had ever starred in a picture together.

And as long as you're not looking for a faithful interpretation of the original text, The Taming of the Shrew is pretty funny, and at 65 minutes, sprightly enough after a drink or two (I recommend the Mary Pickford cocktail) for a fun evening in front of the DVR.

If you're not familiar with the play, The Taming of the Shrew is the story of Petruchio (Fairbanks), a young man on the make looking to marry the richest maiden he can find—and right quick, because he's got important business to attend to. Unfortunately for him, the most readily-available woman is an ill-tempered shrew (Pickford) who cracks a whip, hisses and spits, and breaks lutes over the heads of hapless music teachers.

But Petruchio is unconcerned. He's certain he can curb her temper and break her to his will.

"I am as peremptory as she proud-minded;

And where two raging fires meet together

They do consume the thing that feeds their fury"

How Petruchio tames the shrew—or appears to—is the core of this truncated version of the play. And despite drawing dialogue from Shakespeare, it's largely a slapstick reading of the original text.

Director Sam Taylor, a veteran of Harold Lloyd's heyday, puts a whip in Pickford's hand, and a bigger one in Fairbanks's. He has Fairbanks show up for the wedding dressed in rags and wearing a boot on his head, eating an apple throughout the ceremony then throwing Kate on the back on his horse and heading home in a driving rain before the wedding feast has even begun. There's a pratfall in a pigpen, a soliloquy delivered to a dog, and roughhousing enough for a Three Stooges short.

In little over an hour, Pickford and Fairbanks reduce Shakespeare to a Laurel and Hardy comedy—and I mean that as the sincerest of compliments. Sometimes we get so caught up in the iambic pentameter that we forget that Shakespeare was writing for the masses. He had a fondness for lowbrow humor and I think the Bard would have approved of the slapstick and irreverent staging.

And if he didn't? Well, so what. This is a movie not a literature class, and Taylor's approach is largely a cinematic interpretation of the story, dispensing with heaps of speeches and instead showing what Shakespeare only describes, an approach that will no doubt upset the purists but which appeals to someone like me, a silent movie fan who sometimes find all the yammering chat projected on the big screen since 1927 not only noisy and maddening but unnecessary.

The scene with the dog, for example, is not just funny: by having Petruchio talk aloud to the dog and allowing Kate to overhear him, Taylor eliminates the need for a third character and several more expository speeches. It's not pure Shakespeare, but it is pure cinema, and at a time when Hollywood was in thrall to the talk-talk-talk of the Broadway stage, a refreshing development.

But for those of you who care, just how faithful is this version to the original Shakespeare? Well, it is faithful to the basic plot involving Kate and Petruchio, and the dialogue comes from the text, but the film dispenses with roughly 80% of the play—Kate's sister Bianca and her multiple suitors, the comedy of mistaken identity and the framing device of Christopher Sly and the merry pranksters who sport with him.

In fact, no matter what the opening credits say, this Shrew is actually based on David Garrick's eighteenth century adaptation Catherine and Petruchio, which reworked the original text into a one-act two-person scenario—it's all the meat with none of the bones.

Despite Shakespeare's standing as the greatest playwright of all time, many of his works are problematic and The Taming of the Shrew is no exception. Left unanswered in the original text is an explanation for Kate's behavior, especially her final capitulation which even in 1592 was considered pretty sexist. How a production handles her character will largely determine whether the play is a success or a failure.

This film version opts for what I would call a "feminist" interpretation. Kate is attracted to the first man she can't intimidate but doesn't really falls for him until she "combs his noodle with a three-legged stool" and mothers him back to consciousness.

And for his part, despite the rigid gender roles society has set for them, maybe he likes it that way.

What is the old saying—he chased her until she caught him? Shakespeare seems to be saying that romance is a battle of wills that only ends in true love when a man thinks he has prevailed and a woman knows that she has.

At least that's this film's interpretation.

Anyway.

Despite the equal billing, The Taming of the Shrew is more Fairbanks's film than Pickford's. Kate is a thankless role—blame Shakespeare—but though Pickford later expressed dissatisfaction with her performance and called the experience the worst of her life, she does with the part what she can, pouting beautifully, cracking a mean whip and, most importantly, turning the famous final speech into a winking bit of feminist subterfuge.

Fairbanks, on the other hand, was essentially playing a variation on his best roles, the larger-than-life, hale and hearty, well-met fellow who despite his oddball antics is a loveable guy. Petruchio requires an actor who can chew the scenery and make you like it, and Fairbanks does not disappoint. Despite behind-the-scenes tension that made for an unhappy production, Pickford admitted that Fairbanks's performance was one of the best of his career.

On a budget of $504,000, the film grossed a million dollars at the box office, but despite turning a profit, it didn't serve its essential purpose, to make its stars fashionable again. There were further attempts to crack the commercial cocoanut, but The Taming of the Shrew was the last box office success of either star's career. Pickford and Fairbanks separated soon after filming ended and divorced in 1936.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

Ray Harryhausen, 1920-2013

We here at the Monkey pause to sadly note the passing of Ray Harryhausen, for my money the greatest special effects wizard of all time and apparently a really nice guy to boot. His classic work includes Mighty Joe Young, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts.

Nobody was better making skeletons dance than Ray Harryhausen. We salute you, sir.

Nobody was better making skeletons dance than Ray Harryhausen. We salute you, sir.

Friday, May 3, 2013

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

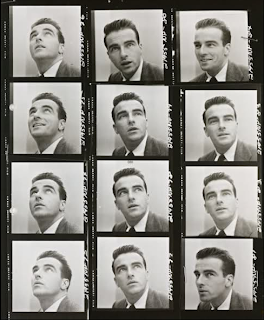

Almost Wasn't Wednesday #4: Sunset Boulevard With Mary Pickford And Montgomery Clift

Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard surely ranks as one of the greatest movies of all time, and perhaps the greatest movie about the movies themselves.

Sunset Boulevard was perfectly cast with Oscar-nominated performances by William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Erich von Stroheim and Nancy Olson, but the film nearly featured very different performers in the lead roles.

Montgomery Clift had already signed on to play struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis before backing out days before filming started. "It so happens Mr. Clift had had an affair with an older woman in New York," Wilder recalled years later. "And he did not want to make his first picture playing the lead, the story of a man being kept by a very rich woman twice his age. He did not want Hollywood talk."

Fred MacMurray turned down the part, and the studio vetoed Wilder's suggestion of Marlon Brando, who at that point had yet to make a movie. Only then did Wilder reluctantly cast Holden, who despite starring in Golden Boy in 1939 had yet to make his mark in Hollywood. The compromise proved to be fortuitous, providing a breakthrough role for Holden, and introducing Wilder to an actor who would go on to star in four of his films.

The female lead proved even harder to cast. Among the many actresses Wilder approached were Mae West, Norma Shearer, Pola Negri, Greta Garbo and—particularly intriguing to me—Mary Pickford. There are many different stories about what happened next.

"Mr. Brackett and I went to see her at Pickfair, but she was too drunk," Wilder later claimed. "She was not interested." On the other hand, Scott Eyman, one of Pickford's biographers, wrote that she was indeed interested but wanted the script rewritten to emphasize Norma Desmond, a change Wilder was not willing to make. Still others have suggested Pickford simply feared damaging her image.

In any event, fellow director George Cukor soon after suggested Swanson, an inspired choice, it turns out. The performance was so good that Barbara Stanwyck kissed the hem of Swanson's skirt at the premiere.

Would the film have been as good with Pickford (or West or Shearer or Negri or Garbo) in the lead? It would have been different, that's for sure. Swanson was something of a larger-than-life figure herself and if you know her silent work, particularly the six films she did with Cecil B. DeMille, you know Norma Desmond was right in her wheelhouse. As Wilder himself noted years later, "There was a lot of Norma in her, you know."

Sunset Boulevard was perfectly cast with Oscar-nominated performances by William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Erich von Stroheim and Nancy Olson, but the film nearly featured very different performers in the lead roles.

Montgomery Clift had already signed on to play struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis before backing out days before filming started. "It so happens Mr. Clift had had an affair with an older woman in New York," Wilder recalled years later. "And he did not want to make his first picture playing the lead, the story of a man being kept by a very rich woman twice his age. He did not want Hollywood talk."

Fred MacMurray turned down the part, and the studio vetoed Wilder's suggestion of Marlon Brando, who at that point had yet to make a movie. Only then did Wilder reluctantly cast Holden, who despite starring in Golden Boy in 1939 had yet to make his mark in Hollywood. The compromise proved to be fortuitous, providing a breakthrough role for Holden, and introducing Wilder to an actor who would go on to star in four of his films.

The female lead proved even harder to cast. Among the many actresses Wilder approached were Mae West, Norma Shearer, Pola Negri, Greta Garbo and—particularly intriguing to me—Mary Pickford. There are many different stories about what happened next.

"Mr. Brackett and I went to see her at Pickfair, but she was too drunk," Wilder later claimed. "She was not interested." On the other hand, Scott Eyman, one of Pickford's biographers, wrote that she was indeed interested but wanted the script rewritten to emphasize Norma Desmond, a change Wilder was not willing to make. Still others have suggested Pickford simply feared damaging her image.

In any event, fellow director George Cukor soon after suggested Swanson, an inspired choice, it turns out. The performance was so good that Barbara Stanwyck kissed the hem of Swanson's skirt at the premiere.

Would the film have been as good with Pickford (or West or Shearer or Negri or Garbo) in the lead? It would have been different, that's for sure. Swanson was something of a larger-than-life figure herself and if you know her silent work, particularly the six films she did with Cecil B. DeMille, you know Norma Desmond was right in her wheelhouse. As Wilder himself noted years later, "There was a lot of Norma in her, you know."