The two best films of 1933 that unfortunately are not going to win any of my self-invented Katie awards are a pair of pre-Code Barbara Stanwyck classics, as different from each other in every respect except quality as two movies can get. I highly recommend you see both.

The two best films of 1933 that unfortunately are not going to win any of my self-invented Katie awards are a pair of pre-Code Barbara Stanwyck classics, as different from each other in every respect except quality as two movies can get. I highly recommend you see both.I've mentioned the term "pre-Code" many times and written about this period in Hollywood history at length here and here. In a nutshell, in order to stave off state and federal attempts to censor movies, Hollywood's studios issued a set of guidelines of what were unacceptable topics for the big screen. Without any enforcement power, though, the guidelines were more often than not honored in the breach, and in fact, New York's National Board of Review and the Catholic League of Decency had a far greater influence on the content of films than Hollywood's own Hays Office. Not until Joseph Breen took over the office in 1934 did Hollywood studios agree to enforce the Code.

Anyone who is a fan of pre-Code movies has in mind some actor or actress who personifies the era's permiss- iveness. For some it's Joan Blondell, for others it's Jean Harlow; still others prefer Miriam Hopkins, Kay Francis, Mae West, Clark Gable, James Cagney or even Norma Shearer. For me, though, Barbara Stanwyck more than any other performer, has come to personify in my mind the essence of the pre-Code era. Not only did she strip down to her skivvies in such films as Night Nurse, but she also displayed a fierce independence than always feels modern to me, even in the creakiest of film vehicles.

Anyone who is a fan of pre-Code movies has in mind some actor or actress who personifies the era's permiss- iveness. For some it's Joan Blondell, for others it's Jean Harlow; still others prefer Miriam Hopkins, Kay Francis, Mae West, Clark Gable, James Cagney or even Norma Shearer. For me, though, Barbara Stanwyck more than any other performer, has come to personify in my mind the essence of the pre-Code era. Not only did she strip down to her skivvies in such films as Night Nurse, but she also displayed a fierce independence than always feels modern to me, even in the creakiest of film vehicles."It would be difficult to think of an actress so expressive of the early 1930s girl on the make," British film historian David Thomson has written, "as intimate, shiny, and flimsy as a discarded slip, but with eyes ever sly and alert."

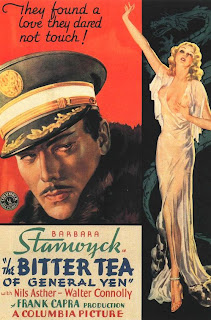

Stanwyck rose quickly to stardom in the pre-Code era, primarily through the films of two great directors, William Wellman (Night Nurse, So Big and The Purchase Price) and Frank Capra, whose early films with Stanwyck included Ladies Of Leisure, The Miracle Woman, Forbidden and in the 1933 film, The Bitter Tea Of General Yen.

General Yen is the story of an American missionary (Stanwyck) who travels to China to marry her rather stuffy fiance only to wind up as the captive of a powerful warlord during the country's interminable civil war. At first, Yen (Nils Asther in the best performance of his career) holds Stanwyck in an effort to blunt the reformist zeal of Stanwyck's fiancé, but he soon finds himself falling in love with her.

General Yen is the story of an American missionary (Stanwyck) who travels to China to marry her rather stuffy fiance only to wind up as the captive of a powerful warlord during the country's interminable civil war. At first, Yen (Nils Asther in the best performance of his career) holds Stanwyck in an effort to blunt the reformist zeal of Stanwyck's fiancé, but he soon finds himself falling in love with her.Stanwyck, for her part, has a hard time reconciling her properly virginal upbringing with her growing lust for Yen, and in the process must confront for the first time in her sheltered life her own hypocrisy and prejudices. Her fevered dream in which she finds herself both menaced by and drawn to Yen is one of the most beautifully filmed sequences of Capra's illustrious career.

The film was a flop upon its initial release and Capra later dismissed it as "the only film in which I ever tried to become arty, because I was trying to win an Academy Award." The notion of a romance between a white woman and an Asian man shocked some and the picture played to protests around the country. "The women’s clubs came out very strongly against it," Stanwyck later said. "I was so shocked."

The film was a flop upon its initial release and Capra later dismissed it as "the only film in which I ever tried to become arty, because I was trying to win an Academy Award." The notion of a romance between a white woman and an Asian man shocked some and the picture played to protests around the country. "The women’s clubs came out very strongly against it," Stanwyck later said. "I was so shocked." Even more shocking was Stanwyck's next film, Baby Face, one of the most notorious films of the pre-Code era. Written by Darryl F. Zanuck, who quit Warner Brothers shortly afterwards to form Twentieth Century Films, Baby Face was so racy that many scenes had to be re-shot and even then two version went out to theaters.

Even more shocking was Stanwyck's next film, Baby Face, one of the most notorious films of the pre-Code era. Written by Darryl F. Zanuck, who quit Warner Brothers shortly afterwards to form Twentieth Century Films, Baby Face was so racy that many scenes had to be re-shot and even then two version went out to theaters.In Baby Face, Stanwyck plays Lily Powers, the daughter of an abusive saloon keeper who's been pimping her out since she was fourteen years old. She's inured to the humiliation—the look on her face as she realizes her father has just pimped her out is perfectly underplayed, as bored and blase as if he'd just read her the out-of-town baseball scores, but underneath seething with resentment—but she yearns for something better and is beginning to understand the power of her own sexuality.

In a key early scene that sets the tone, a powerful local politician puts his hand on Lily's knee, expecting to put his hand on a lot more than that. With barely a glance, Lily picks up a cup of coffee and casually dumps it on him.

In a key early scene that sets the tone, a powerful local politician puts his hand on Lily's knee, expecting to put his hand on a lot more than that. With barely a glance, Lily picks up a cup of coffee and casually dumps it on him."Oh, excuse me, my hand shakes so when I'm around you." When she later breaks a bottle over his head, he finally gets the message that this isn't foreplay.

With her only friend Chico (Theresa Harris), Lily leaves her father and hops a freight train—sleeping with a railroad cop to avoid arrest—and winds up in the big city where she ruthlessly sleeps her way to the top. (Among her conquests, look for a young John Wayne.)

Baby Face won no awards, but in 2005, the Library Congress included the film in the National Film Registry. If you're going to see it, make sure to track down the uncut version, which was for years thought lost then rediscovered in 2004. It's worth seeing both as a reminder that Hollywood didn't invent sex and sin in 1967, and as a pivotal moment in Stanwyck's career, being to my mind the moment she really became what we think of as "Barbara Stanwyck," with the impudence of Bette Davis, the independence of Katharine Hepburn, and the street smarts of Joan Crawford, only warmer, sexier and much less neurotic, respectively.

Baby Face won no awards, but in 2005, the Library Congress included the film in the National Film Registry. If you're going to see it, make sure to track down the uncut version, which was for years thought lost then rediscovered in 2004. It's worth seeing both as a reminder that Hollywood didn't invent sex and sin in 1967, and as a pivotal moment in Stanwyck's career, being to my mind the moment she really became what we think of as "Barbara Stanwyck," with the impudence of Bette Davis, the independence of Katharine Hepburn, and the street smarts of Joan Crawford, only warmer, sexier and much less neurotic, respectively. Within a year, the studios began to enforce the strict guidelines of the Pro- duction Code and Holly- wood wouldn't again make films with content as explicit and controversial as The Bitter Tea Of General Yen and Baby Face until the 1960s. Stanwyck herself shifted gears and found popularity playing the martyred mother in such films as Stella Dallas. Not until The Lady Eve in 1941 would she figure how to sell the public on a character as brazen as Lily Powers.

Within a year, the studios began to enforce the strict guidelines of the Pro- duction Code and Holly- wood wouldn't again make films with content as explicit and controversial as The Bitter Tea Of General Yen and Baby Face until the 1960s. Stanwyck herself shifted gears and found popularity playing the martyred mother in such films as Stella Dallas. Not until The Lady Eve in 1941 would she figure how to sell the public on a character as brazen as Lily Powers.Trivia: The Bitter Tea Of General Yen was the first movie ever to play Radio City Music Hall in New York. Scheduled to run for two weeks, the theaters owners yanked the film after eight days despite having made back only $80,000 of the $100,000 rental they had paid the studio.

Seen just about every film in your post. I like Babyface, but The Bitter Tea Of General Yen was never one of my favorites.

ReplyDeleteLove those pre-codes.

Great essay! I like The Bitter Tea of General Yen. I thought it was interesting as a somewhat historical look at China of the time as well as the controversial romance. Thanks!

ReplyDelete