Les Vampires—The Best Movie(s) Of 1915

Les Vampires—The Best Movie(s) Of 1915Almost from cinema's beginning, recurring characters were popular with filmmakers and theatergoers alike. With the actor's persona—Max Linder's comically clumsy bon vivant, for example—clearly established before the film had even begun, audiences knew what to expect and could make their choices with some confidence; directors meanwhile could dispense with character exposition, which ate up precious film time, and get right to the action.

The progression from films featuring recurring characters to films with interlinked stories that starred those characters was a natural one, and the concept was as old as the serialized fiction that was sold in magazines, one chapter per issue, in the nineteenth century.

"Serials extended one story line through a dozen or more chapters," Daniel Eagan wrote in America's Film Legacy, "much like the daily and weekly comic strips that were growing in popularity around the turn of the twentieth century. A film that didn't end but continued on, that required viewers to return to theaters to find out what happened next, seemed like a gold mine to producers and exhibitors."

Typically, any given chapter of a film serial would feature plenty of action, and end with the hero (actually, almost always the heroine) in danger, with their predicament not resolved until the next episode. In fact, so often was the heroine left hanging by her fingernails from a cliff at the end of a given episode, the term "cliffhanger" came to mean a suspenseful situation left unresolved at the story's end.

Typically, any given chapter of a film serial would feature plenty of action, and end with the hero (actually, almost always the heroine) in danger, with their predicament not resolved until the next episode. In fact, so often was the heroine left hanging by her fingernails from a cliff at the end of a given episode, the term "cliffhanger" came to mean a suspenseful situation left unresolved at the story's end. Unless you want to count the multi-part Passion Play produced in 1903, the first serial may have been Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset's Nick Carter series, which ran in French theaters in 1908. Thomas Edison popularized the concept in the United States with his What Happened to Mary? series in 1912, George B. Selig's The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913) was the first to truly link episodes together into a single plotline, and The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine, both starring Pearl White, were among the most popular movies of 1914.

Unless you want to count the multi-part Passion Play produced in 1903, the first serial may have been Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset's Nick Carter series, which ran in French theaters in 1908. Thomas Edison popularized the concept in the United States with his What Happened to Mary? series in 1912, George B. Selig's The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913) was the first to truly link episodes together into a single plotline, and The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine, both starring Pearl White, were among the most popular movies of 1914.Serials were most popular during the silent era, but continued to be a staple of Saturday morning matinees until the advent of television.

The greatest director of serials—the one who turned genre escapism into lasting art—was the Frenchman, Louis Feuillade. Feuillade (pronounced "Foo-yaad") had already had a big hit in 1913 with Fantômas, five interlinked feature films based on a series of novels about a murderous master criminal, one of film history's first anti-heroes.

The greatest director of serials—the one who turned genre escapism into lasting art—was the Frenchman, Louis Feuillade. Feuillade (pronounced "Foo-yaad") had already had a big hit in 1913 with Fantômas, five interlinked feature films based on a series of novels about a murderous master criminal, one of film history's first anti-heroes.Even better was Les Vampires, a ten-part, seven hour serial released in France between November 13, 1915, and June 30, 1916. Not only is it the best serial ever produced,

it's on a short list of the best films of the silent era. Inspired by the vicious exploits of the real life Les Apaches and Bonnot gangs that terrorized Paris during the Belle Époque, Les Vampires (pronounced "lay vam-peer") tells the story of a criminal organization, The Vampires, whose reach extends into the highest levels of French government and society, corrupting those it can, terrorizing and murdering those it can't.

it's on a short list of the best films of the silent era. Inspired by the vicious exploits of the real life Les Apaches and Bonnot gangs that terrorized Paris during the Belle Époque, Les Vampires (pronounced "lay vam-peer") tells the story of a criminal organization, The Vampires, whose reach extends into the highest levels of French government and society, corrupting those it can, terrorizing and murdering those it can't.With the justice system unable or unwilling to bring the Vampires to heel, an enterprising newspaper reporter, Phillipe Guerande, teams up with a turncoat member of the gang itself, and takes on the Vampires himself, first by exposing its secrets, then through direct confrontation.

"All the roots of the thriller and suspense genres," David Thomson wrote, "are in Feuillade's sense that evil, anarchy and destructiveness speak to the frustrations banked up in modern society. ... Not only has Feuillade's pregnant view of grey streets become an accepted normality; his expectations of conspiracy, violence, and disaster spring at us every day."

The first episode—ominously titled "The Severed Head"—finds Guerande framed for fraud and murder. The second episode sees his fiancee poisoned and Guerande kidnapped and sentenced to death by the Grand Vampire himself.

The first episode—ominously titled "The Severed Head"—finds Guerande framed for fraud and murder. The second episode sees his fiancee poisoned and Guerande kidnapped and sentenced to death by the Grand Vampire himself.And this isn't even the good stuff.

Both episodes are slam-bang and lots of fun, but they barely hint at the invent- iveness of the serial which doesn't hit its stride until the arrival in the third episode of the sinister, seductive Irma Vep, one of the greatest characters in the entirety of silent cinema.

Both episodes are slam-bang and lots of fun, but they barely hint at the invent- iveness of the serial which doesn't hit its stride until the arrival in the third episode of the sinister, seductive Irma Vep, one of the greatest characters in the entirety of silent cinema.Played by Musidora in the style of screen vamp Theda Bara, Irma Vep—which, as a lobby card outside a music hall reveals when it magically rearranges the letters of the name, is an anagram of Vampire—puts the fatal back in femme fatale. Although in terms of screen time, she fills what amounts to a supporting role, Irma Vep is, as Fabrice Zagury wrote in his essay "The Public is My Master: Louis Feuillade and Les Vampires, "the one pulling the strings," using the power of seduction—and murder, too—to bend the putative leaders of the Vampires to her will.

You can't take your eyes off her. It's my favorite performance of the year.

"Musidora," wrote Tom Gunning in his essay The Terrifying Yet Scintillating Origins of IRMA VEP, "clothed in her close-fitting black bodysuit, her maillot de soie, robbed, kidnapped, and murdered, and seized the imagination of a generation. For the devotees of Musidora’s silent films, that fascination survived for decades. The surrealists worshiped her amoral sexuality, and the revolutionary poet Louis Aragon later claimed that Irma Vep’s dark bodysuit inspired the youth of France with fantasies of rebellion."

"Musidora," wrote Tom Gunning in his essay The Terrifying Yet Scintillating Origins of IRMA VEP, "clothed in her close-fitting black bodysuit, her maillot de soie, robbed, kidnapped, and murdered, and seized the imagination of a generation. For the devotees of Musidora’s silent films, that fascination survived for decades. The surrealists worshiped her amoral sexuality, and the revolutionary poet Louis Aragon later claimed that Irma Vep’s dark bodysuit inspired the youth of France with fantasies of rebellion."Indeed, Feuillade consciously subverts the morality of his cops and robbers tale by casting against the alluring Musidora the dullest of dull actors, the blandly handsome Édouard Mathé, as the putative hero, and the delightfully hammy Marcel Lévesque as his bumbling, Clouseau-like sidekick, Oscar Mazamette. Only because you'd hate to see any harm come to Mazamette can you sympathize with the heroes at all.

That Feuillade's criminals were sexier, more intriguing and, perhaps more to the point, more successful than their law-abiding conterparts was not lost on French authorities. Paris police halted production and banned release of the serial on the grounds it glorified crime (which it most certainly does), a decision that wasn't reversed until Musidora herself showed up at the chief of police's office to do a little one-on-one lobbying.

That Feuillade's criminals were sexier, more intriguing and, perhaps more to the point, more successful than their law-abiding conterparts was not lost on French authorities. Paris police halted production and banned release of the serial on the grounds it glorified crime (which it most certainly does), a decision that wasn't reversed until Musidora herself showed up at the chief of police's office to do a little one-on-one lobbying. "Surrealists [such as André Breton and Luis Buñuel] discovered in Les vampires a form of subversion that was fully compatible with their own aesthetic designs," wrote Jonathan Rosenbaum in 1987 for the Chicago Reader (reprinted here on his own website.)

"Surrealists [such as André Breton and Luis Buñuel] discovered in Les vampires a form of subversion that was fully compatible with their own aesthetic designs," wrote Jonathan Rosenbaum in 1987 for the Chicago Reader (reprinted here on his own website.)It's no wonder the surrealists loved Feuillade—his Paris is simultaneously whimsical and deadly, a place where you can lean out a second-story window and wind up with a lasso around your neck, where every cupboard hides a body, every hatbox a head, and your neighbor's loft conceals a cannon. There's no sense of safety—or sanity—anywhere. People are murdered on trains, in cafes, and even in their own beds. Perhaps that's why I, as a 21st century movie fan, find Feuillade's work so engaging—he anticipated the anxieties that came to define the 20th century and continue to plague us to this day: violence, paranoia, alienation, conspiracy, terrorism.

It also has a wonderfully nutty quality, the sense that anything could happen and often does.

"Feuillade's cinema," said Alain Resnais, "is very close to dreams—therefore it's perhaps the most realistic."

"Feuillade's cinema," said Alain Resnais, "is very close to dreams—therefore it's perhaps the most realistic." "[T]he orginality of Lang and Hitchcock" (Thomson again) "fall into place when one has seen Feuillade: Mabuse is the disciple of Fantômas; while Hitchcock's persistent faith in the nun who wears high heels, in the crop-spraying plane that will swoop down to kill, and in a world mined for the complacent is inherited from Feuillade." Both Lang and Hitchcock (as well as Buñuel) were directly influenced by Feuillade's work.

"[T]he orginality of Lang and Hitchcock" (Thomson again) "fall into place when one has seen Feuillade: Mabuse is the disciple of Fantômas; while Hitchcock's persistent faith in the nun who wears high heels, in the crop-spraying plane that will swoop down to kill, and in a world mined for the complacent is inherited from Feuillade." Both Lang and Hitchcock (as well as Buñuel) were directly influenced by Feuillade's work.Equally subversive in the eyes of its original audience, Zagury points out, (if lost on viewers today) is Irma Vep's ability to move freely between the various classes that make up French society. That Irma can so easily pass herself off first as a chambermaid then as an aristocrat and then even as a man was a direct affront to the ruling elite's faith that it was imbued with special qualities that justified its exalted position in the nation's power structure. (George Bernard Shaw explored a similar theme in his comedy Pygmalion.)

In making my case for the films of Louis Feuillade, I want to avoid the tendency of many writers to simultaneously dismiss the contemporaneous works of D.W. Griffith, whose The Birth of a Nation was released the same year, to argue, as Rosenbaum does, that "Feuillade is as cool and hip as Griffith is overheated and square," or as Thomson does, that Feuillade's camera work is "relaxed, subtle" while "Griffith's is pompous and prettifying."

In making my case for the films of Louis Feuillade, I want to avoid the tendency of many writers to simultaneously dismiss the contemporaneous works of D.W. Griffith, whose The Birth of a Nation was released the same year, to argue, as Rosenbaum does, that "Feuillade is as cool and hip as Griffith is overheated and square," or as Thomson does, that Feuillade's camera work is "relaxed, subtle" while "Griffith's is pompous and prettifying."The fact is, both Griffith and Feuillade were indispensable in defining what we see when we go to the movies, and it took both men to give us, say, Alfred Hitchcock, whose certainty that anything could and should happen on screen was inherited from Feuillade while his masterful use of the classical Hollywood editing style to show us his often surreal action he inherited from its chief pioneer, Griffith. Fortunately, we know (don't we?) that film history isn't an either/or proposition—it's an and/and one. And thus, the choice isn't Griffith or Feuillade, Chaplin or Keaton, or even silent film or sound. It's all of them, and I want to see all of them, and you should want to see all of them, too.

Feuillade continued to direct right up to his death in 1925, including two more masterpieces of the crime genre, Judex, which I have seen, and Tih Minh which I have not.

Like Phillipe Guerande, Feuillade began his career as a reporter, and after he made the jump to movies, he drew on his own experiences to shape his stories. Feuillade was a workaholic, writing and directing over 700 short films between 1906 and 1924, working like a man chased by some unseen demon. "I haven't a minute to lose," he often said while turning down requests for interviews.

Like Phillipe Guerande, Feuillade began his career as a reporter, and after he made the jump to movies, he drew on his own experiences to shape his stories. Feuillade was a workaholic, writing and directing over 700 short films between 1906 and 1924, working like a man chased by some unseen demon. "I haven't a minute to lose," he often said while turning down requests for interviews.Although convinced film was an art form rather than a pure novelty, Feuillade believed his first duty was to entertain. "I consider cinema as a place for rest, cheerfulness, soft emotions, dreams, forgetfulness. We don't go to the movies to study. The public flocks to it to be entertained. I place the public above everything else."

His attitude did not endear him to the generation of French filmmakers who followed him. "The interest of the young filmmakers of the time," René Clair said later, "was diametrically opposed to commercial entertainments made by the prolific author of Judex of which they talk mostly with disdain."

As a result, Feuillade was largely forgotten after his death in 1925 until Henri Langlois—the same film historian who helped make Louise Brooks famous—resurrected his reputation. Along with the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès, Feuillade is now revered as one of the founders of French cinema.

As a result, Feuillade was largely forgotten after his death in 1925 until Henri Langlois—the same film historian who helped make Louise Brooks famous—resurrected his reputation. Along with the Lumière brothers and Georges Méliès, Feuillade is now revered as one of the founders of French cinema.His Les Vampires is also proof that no matter how old, a great movie, like all great art, is timeless.

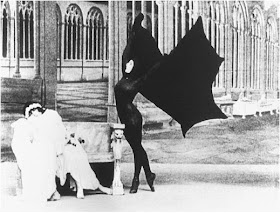

While The Real Musidora Please Stand Up? Here, by the way, is probably the most famous picture of Musidora, the one that always crops up when people post pictures from Les Vampires on the internet:

There's only problem—that's not Musidora, it's Stacia Napierkowska who plays Guerande's fiancee Marfa Koutiloff in the second episode. She's on screen for maybe five minutes, dancing in a ballet about vampires.

There's only problem—that's not Musidora, it's Stacia Napierkowska who plays Guerande's fiancee Marfa Koutiloff in the second episode. She's on screen for maybe five minutes, dancing in a ballet about vampires.The second most popular picture of Musidora isn't Musidora either; it's Maggie Cheung essentially playing Musidora in the 1996 movie Irma Vep:

This is Musidora. You can perhaps see where the confusion arises.

This is Musidora. You can perhaps see where the confusion arises. But now you know. Just another in a long line of services we provide free here at the Monkey.

But now you know. Just another in a long line of services we provide free here at the Monkey.To continue to Part Three, click here.

Wonderful article. I really enjoyed it. I so long to see silent films; but alas, they come along few and far between.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Jeanie! Les Vampires is one of the most entertaining silent movies I've seen. The DVD is out of print now I think although I'm pretty sure it's available through Netflix. Seven hours is a lot of movie, but it's in ten separate episodes, so there's no reason to watch it all in one sitting.

ReplyDeletelay vam-peer

ReplyDeleteWhy, I don't mind if I do!

bada *bing* !

I gave up my Netflix account; but if this is a resource for silent films, I may re-think my decision! The holy grail for me (and many others, I think) would be to see "Greed" in any form I could find it.

ReplyDeleteThe holy grail for me (and many others, I think) would be to see "Greed" in any form I could find it.

ReplyDeleteWhy Greed is not on DVD is incomprehensible.

I will say the 4-hour semi-restoration (using stills and the surviving film) is floating around on YouTube -- not the ideal way of seeing it, but better than nothing. And it crops up on TCM from time to time.

I myself still have that VHS copy in the basement. I've whittled the old VHS tapes down quite a bit (where they overlap with DVD) but they still come in handy from time to time.

And for Charles Hawtrey ...

ReplyDeleteIt is unutterably sad that silent films do not (in my estimation) receive the respect they deserve. Millions are spent churning out the dreck that passes for entertainment in the film industry, but precious little goes toward the restoring of the legacy of film. I guess I sound like one of TCM's commercials for film restoration! Sometimes I think how some of these treasured reels may be sitting in someone's attic just rotting away and it just makes me sad. OK - rant for the day is over.

ReplyDeleteMM, you have written an elegant exploration of Louis Feuillade the filmmaker and the history of serialized silent films (the background information on silent cinema fascinates me). I agree it is a combination of camp and subversion that make Feuillade’s films fascinating and relevant almost one hundred years later. I also admire your balanced approach to both Feuillade and Griffith’s contributions to the development of silent cinema as an art form. Thank you especially for clearing up the confusion on Musidora; I made the mistake of assuming she was the woman in the bat-winged costume. I have actually seen IRMA VEP (1996) with Maggie Cheung and her latex body suit. I thought the film was interesting as France exploring and embracing it’s cinema history, and the footage from LES VAMPIRES was a treat, but for weeks I couldn’t get the Serge Gainsbourg ~ Brigitte Bardot song out of my head: Bonnie and Clyde.

ReplyDeleteThank you especially for clearing up the confusion on Musidora

ReplyDeleteI admit, I brought up the whole "will the real Musidora please stand up" thing because when I first started making notes on Les Vampires last fall, I had a hard time figuring out who was who.

In fact, an awful lot of this blog is motivated by what I don't know about the movies.

It is unutterably sad that silent films do not (in my estimation) receive the respect they deserve.

ReplyDeleteI'm with you. But I have to admit (a day for admissions) that two years ago when I started blogging, I didn't know all that much about silent movies. It was only because I felt like I needed to get a handle on them that I really began to watch them in earnest. At first it was more out of sense of duty, I think, but something happened -- maybe seeing The General at the Kennedy Center with a live orchestra -- and I fell in love with silent movies. Now sometimes when I watch newer movies I think, "Why are they talking so much?"

Once you get past the strangeness of what is essentially a different medium, you realize how beautiful silent movies are, and how timeless so many of them are.

Thanks Myth; now i've got me a Netflix all my own & now I've got to see this. But you know, no matter how good it is, no silent film can ever take the place of MY favorite serial. No sir. Well I think they probably stopped making this one before you were born young man, right about when they started into all that vitamin and fiber nonsense, fluoridating the water and going off the gold standard, and everything went to hell, you know what i mean? But I used to eat this by the bucketful -- it kept me going strong, day and night.

ReplyDeleteWho, I'm just old enough to remember when Sugar Crisp (and Capt. Crunch and Frosted Flakes) were part of a nutritious breakfast, along with bacon and scrambled eggs.

ReplyDeleteI also know that the wise old owl says it takes three licks to get to the center of a tootsie pop. Crazy old bird.

What I really found sad was when Saturday morning cartoons suddenly were required to have a moral. It was around 1971 or so, and after growing up with Jonny Quest and Bullwinkle and Bugs Bunny and other socially worthless but oh so wonderfully creative treasures, it was all "Kids, don't do drugs!" kind of stuff.

Then cartoons turned into thinly-disguised ads for toys. Now they're back to being socially unredeeming.

I prefer socially unredeeming.

Entertainment media feel the need to justify themselves by featuring some sort of uplifting message. They want to be considered socially relevant. But there is nothing wrong with just losing yourself in being entertained - and getting away from our stress for just a little while. That's what entertainment was originally meant to be. I hope they will never feel the need to add any redeeming message in the Roadrunner constantly making a fool out of Wile E Cayote.

ReplyDeleteI think politics works best in art when you just tell your story, make the characters and their actions true to life, and then let the chips fall where they may.

ReplyDeleteOne Froggy Evening, for example, contains all the politics and economics and social commentary you'd ever want without even opening its mouth. Beyond that, it's just gilding the lily.