Tomorrow is the fiftieth anniversary of the network premiere of Lost in Space. To celebrate, I'm posting a series of essays including this one which is brand spanking new.

When, lo these many months ago, I first began this series of essays about Lost in Space, it was mostly from nostalgia, revisiting a show that I loved as a kid. And I've enjoyed the effort.

But in the long run, pure nostalgia has little purchase on my brain, else I'd be raving now about Nanny and the Professor. The question is whether Lost in Space holds up now, viewed with adult eyes — and more to the point, your eyes.

It depends, of course.

If your measuring stick is so-called serious science fiction, Star Trek, say, you're almost certain to be disappointed. Although the two are often yoked together — they both aired in the mid-1960s — Star Trek and Lost in Space were in fact conceived as very different shows, mining wholly separate veins to tell different kinds of stories.

At its best, Lost in Space was a fairy tale filled with monsters, magical devices and moral lessons wrapped up in a vaguely science fiction setting. Other times, it was a slapstick comedy featuring a transgressive psychopath and a wisecracking, passive-aggressive robot — Red Dwarf by way of Pee-Wee's Playhouse. And the rest of the time, it was a traditional television Western with gunfights, frontier hardships and passing troublemakers (riding rockets instead of horses) in an outer space situated somewhere between Dodge City and the Big Dipper.

And there's nothing wrong with that.

Rod Serling, who defined science fiction as "the improbable made possible" and fantasy as "the impossible made probable," made a fortune writing in both genres. The point is to tell a good story and if in the process you can peel back the bark of polite society to reveal the human truth underneath, then you've really got something. Fairy tales endure because they allow us to confront our darkest fears — death, failure, loneliness — at a comfortable, magical remove.

For example, "My Friend, Mr. Nobody", about Penny's not-so-imaginary imaginary friend, is at its heart a poignant story of childhood loneliness and the struggle for purpose and relevance. "Wish Upon a Star" uses an unexplained alien artifact that grants every wish to explore the impact of greed on a group's sense of community and individual responsibility. And "Follow the Leader", a story ostensibly about Professor Robinson's possession by a hostile alien spirit, becomes a somber, frightening parable of "alcoholism in the nuclear family."

These stories, along with many others, used elements commonly associated with fantasy to say something true about basic human experiences such as family, community, courage, survival, sexism, and even death.

Admittedly, Lost in Space wasn't, shall we say, well-grounded in scientific accuracy. It was the sort of show that thought a radio telescope is a telescope with a radio on it. Nor did anyone seem to consider whether building an interstellar ship to transport but a single family made much sense. Generally, we prefer to clothe out scientific impossibilities — warp drives, light sabers, dinosaur clones, liquid metal terminators — in the garb of plausible mumbo jumbo.

But scientific plausibility, I contend, is beside the point. I mean, have you gone back and watched an episode of The Twilight Zone recently?

A greater stumbling block for many is Dr. Smith, the most famous — infamous — character on this or any other show. He was lazy, whiny, selfish, conniving, an all-around irritant. But might I suggest that instead of running away from Smith, you should embrace him as television's first true anti-hero.

Think about it. Long before The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Dexter or any of the other truly bad men of television's new Golden Age, indeed, at a time when Hollywood was only just beginning to shed the strictures of the Production Code, a major network built a show — a family show, mind you — around a villain who week-in and week-out plotted to murder, kidnap, betray, ransom and otherwise sell out the series' ostensible heroes. And he never received his comeuppance. There was no precedent for him.

Groundbreaking.

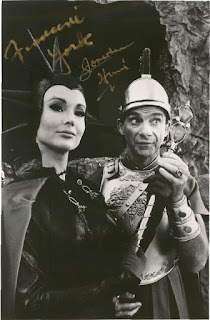

"Of all the many myriad characters that I have played in my life," Jonathan Harris said later, "he surely is my favorite. I like to feel that I would never in a million years have done what he did," but then added with a twinkle, "Maybe. You never know."

Still, context is everything and as you watch Smith do his nefarious thing every week, you have to ask yourself why the other characters put up with him.

The Robot's relationship with Dr. Smith, I think we instinctively get. They're Abbott and Costello, a wisecracking odd couple who fundamentally loathe each other but can't function apart. "He was my alter ego," Harris said, "and he was wise to me and a danger to me. Always calling him those dreadful alliteratives to keep him down so he wouldn't expose me."

Will's relationship with Smith is a bit harder to explain. While no responsible parent would allow a ten year old to run around with a middle-aged man of such dubious moral character, I certainly don't agree with those weisenheimers who've joked that Smith was an intergalactic pedophile. Nor do I wholly agree with Bill Mumy's assessment of Will as "young enough to be naive and manipulated." Nobody's that gullible, especially not a kid as bright as Will Robinson.

No, personally, I think that while Will was smart, honest, brave and resourceful — "smarter than the adults," Mumy said — he was also recklessly adventurous, and far from being Smith's pliable dupe, he (perhaps unwittingly) sought Smith out as a scapegoat for all the trouble he'd be getting into anyway.

"[He] knows he's got the answer that they don't," Mumy said, "and is he going to sneak out and save their butts or is he going to stay in like dad says and let everybody get messed up?"

That's why we put up with this odd relationship — we know that Will wants it's that way.

Less explicable is why the rest of the Robinsons put up with Smith. Fool me once, shame on you; fool me once a week for three straight years and that's just pathological. Maybe their willingness to overlook his repeated attempts to screw them over was meant as a sly commentary on society's tendency to pay lip service to simple virtues while rewarding psychopathic behavior.

How better to explain Donald Trump?

"Lost in Space's vision of a totally ill-prepared family blasting into space with a demented egomaniac along for the ride," wrote Hugo-award-winning author Charlie Jane Anders, "is intrinsically subversive, when compared to more militaristic (or professionalized) views of space exploration. Basically, Lost in Space is the apotheosis of camp — and it's a gloriously weird vision of our future among the stars."

Indeed, in 1968, the American Council for Better Broadcasts complained "the show is marked by violence, greed, selfishness, trickery and a disregard for accepted values!"

No wonder I like it so much.

But will you like it? Ultimately, your willingness to embrace — or at least tolerate — the campy aspects of what television historian James Van Hise called "TV's first science fiction sitcom" will determine whether you'll enjoy more than a handful of episodes.

Camp is deceptively easy to write and almost impossible to pull off. It's based on a broadly winking compact between the performer and the audience that not only does nothing on the screen really matter but also that we're fools for ever thinking it did. Done well, camp can deconstruct a genre to reveal the eternal human truths underneath and make us laugh in self-recognition. But done poorly, as unfortunately it most often is, the result is an undercooked dish of lazy contempt that's hard to swallow.

The byplay between Smith and the Robot was often brilliant and when served up as a counterpoint to the more serious scenes — check out the aforementioned "Follow the Leader" or the third season episode "The Anti-Matter Man" to see what I mean — the comedy could punch up what might otherwise play as earnest, stodgy or worse, ludicrous. But as much as the writers tried, you couldn't build entire episodes around it, any more than you can build a song on nothing but a drum solo.

The problem was not that the series got campy, the problem is that the writers got lazy — I mean, seriously, an episode starring a talking carrot? Come on! — and Irwin Allen, who was at heart a kid with a sweet tooth for schlock, let them get away with it.

Still, it made for decent ratings — finishing in the top 35 in each of its three seasons (Star Trek never finished better than 52nd) — and fifty years later, the brilliant episodes are still brilliant, and the not-so-brilliant ones, well, Smith and the Robot at the very least make me laugh. That's more than good enough for me.

Somewhere between the start of this series back in March and part 3 here, I stopped seeing Lost in Space with the nostalgic eye of a boy and found myself appreciating it with the discerning eye of a grown man. Nostalgia is a double-edged sword, giving value to old ties and traditions, but robbing you of the pleasure of the moment you're living in (Christmas, anyone?). I'll miss the Lost in Space that played for so long in my less-than-perfect memory, but I welcome the pleasure I've felt at discovering something new, something that I missed the first time around.

Lost in Space isn't quite the series I remembered. But I've grown to love it again, in some ways more than I did before. Maybe, given a chance, you'll grow to love it, too.

Tomorrow: Part 4, What To Watch.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Direct all complaints to the blog-typing sock monkey. I only work here.