Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard surely ranks as one of the greatest movies of all time, and perhaps the greatest movie about the movies themselves.

Sunset Boulevard was perfectly cast with Oscar-nominated performances by William Holden, Gloria Swanson, Erich von Stroheim and Nancy Olson, but the film nearly featured very different performers in the lead roles.

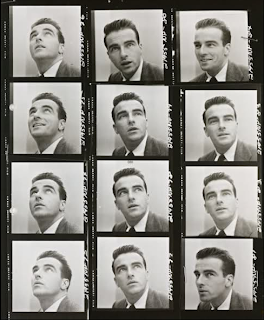

Montgomery Clift had already signed on to play struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis before backing out days before filming started. "It so happens Mr. Clift had had an affair with an older woman in New York," Wilder recalled years later. "And he did not want to make his first picture playing the lead, the story of a man being kept by a very rich woman twice his age. He did not want Hollywood talk."

Fred MacMurray turned down the part, and the studio vetoed Wilder's suggestion of Marlon Brando, who at that point had yet to make a movie. Only then did Wilder reluctantly cast Holden, who despite starring in Golden Boy in 1939 had yet to make his mark in Hollywood. The compromise proved to be fortuitous, providing a breakthrough role for Holden, and introducing Wilder to an actor who would go on to star in four of his films.

The female lead proved even harder to cast. Among the many actresses Wilder approached were Mae West, Norma Shearer, Pola Negri, Greta Garbo and—particularly intriguing to me—Mary Pickford. There are many different stories about what happened next.

"Mr. Brackett and I went to see her at Pickfair, but she was too drunk," Wilder later claimed. "She was not interested." On the other hand, Scott Eyman, one of Pickford's biographers, wrote that she was indeed interested but wanted the script rewritten to emphasize Norma Desmond, a change Wilder was not willing to make. Still others have suggested Pickford simply feared damaging her image.

In any event, fellow director George Cukor soon after suggested Swanson, an inspired choice, it turns out. The performance was so good that Barbara Stanwyck kissed the hem of Swanson's skirt at the premiere.

Would the film have been as good with Pickford (or West or Shearer or Negri or Garbo) in the lead? It would have been different, that's for sure. Swanson was something of a larger-than-life figure herself and if you know her silent work, particularly the six films she did with Cecil B. DeMille, you know Norma Desmond was right in her wheelhouse. As Wilder himself noted years later, "There was a lot of Norma in her, you know."

Showing posts with label William Holden. Show all posts

Showing posts with label William Holden. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Alexandra Petri's New Oscar Categories (Taken More Seriously Than She Intended) (Part Four)

(What is this? Read here.)

Best Performance in a Movie That Involves Running Away From No Fewer Than Two Explosions

How many explosions were there in the first Die Hard movie—well, let's see, there was one on the roof, and one in the elevator and—well, that's two right there. So I'm going with Bruce Willis in Die Hard, which is not just a great action picture, but a great picture, period.

Best Musician Trying To Cross Over Into Acting

If singers count as musicians, it'd be either Will Smith or Frank Sinatra, and since I've already gone with Smith in an answer, let's say Sinatra in From Here To Eternity, The Man with the Golden Arm and The Manchurian Candidate.

If, on the other hand, an actual musical instrument must be played, then I'm going with a personal favorite, pianist Oscar Levant, who was hilarious in Humoresque and An American in Paris. "I'm a concert pianist. That's a pretentious way of saying I'm ... unemployed at the moment." I can dig it, Oscar. It works the same for writers, too.

Best Performance as an Aging Character Who Wants to Prove He or She's Still Got It

There are a lot of good ones to choose from—Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, Bette Davis in All About Eve, John Wayne in The Shootist, Orson Welles in Touch of Evil, and that's just off the top of my head—but I'm going with William Holden in The Wild Bunch. As I wrote a year ago, "I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it. But as Dylan Thomas pointed out, there's more than one way to grow old: you can go quietly into the night, or you can rage, rage against the dying of the light. Pike chooses to rage. And oh how he rages."

Best Performance Involving a Single Manly Tear

That's easy—the native American in the that late-1960s public service ad lamenting the casual littering of the American landscape. Really, people used to throw their trash out the car window without a second thought. This one ad did more to change attitudes than probably all the other ads and speeches on the subject combined.

And no, I have no evidence to support that. Just my personal impression.

Best Performance Where You Have to Age Citizen-Kane-Style Over Years and Years

Another easy one—Orson Welles in Citizen Kane! Sometimes they just softball it in there for you.

Tomorrow: dogs, gays, boats, sandals and parents.

Best Performance in a Movie That Involves Running Away From No Fewer Than Two Explosions

How many explosions were there in the first Die Hard movie—well, let's see, there was one on the roof, and one in the elevator and—well, that's two right there. So I'm going with Bruce Willis in Die Hard, which is not just a great action picture, but a great picture, period.

Best Musician Trying To Cross Over Into Acting

If singers count as musicians, it'd be either Will Smith or Frank Sinatra, and since I've already gone with Smith in an answer, let's say Sinatra in From Here To Eternity, The Man with the Golden Arm and The Manchurian Candidate.

If, on the other hand, an actual musical instrument must be played, then I'm going with a personal favorite, pianist Oscar Levant, who was hilarious in Humoresque and An American in Paris. "I'm a concert pianist. That's a pretentious way of saying I'm ... unemployed at the moment." I can dig it, Oscar. It works the same for writers, too.

Best Performance as an Aging Character Who Wants to Prove He or She's Still Got It

There are a lot of good ones to choose from—Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard, Bette Davis in All About Eve, John Wayne in The Shootist, Orson Welles in Touch of Evil, and that's just off the top of my head—but I'm going with William Holden in The Wild Bunch. As I wrote a year ago, "I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it. But as Dylan Thomas pointed out, there's more than one way to grow old: you can go quietly into the night, or you can rage, rage against the dying of the light. Pike chooses to rage. And oh how he rages."

Best Performance Involving a Single Manly Tear

That's easy—the native American in the that late-1960s public service ad lamenting the casual littering of the American landscape. Really, people used to throw their trash out the car window without a second thought. This one ad did more to change attitudes than probably all the other ads and speeches on the subject combined.

And no, I have no evidence to support that. Just my personal impression.

Best Performance Where You Have to Age Citizen-Kane-Style Over Years and Years

Another easy one—Orson Welles in Citizen Kane! Sometimes they just softball it in there for you.

Tomorrow: dogs, gays, boats, sandals and parents.

Friday, November 30, 2012

Golden Boy: The 75th Anniversary Broadway Revival Of The Clifford Odets Play

This last Tuesday afternoon, Mister Muleboy and I made our way to Manhattan for a V.I.P. preview of Golden Boy, a revival of a 1937 Clifford Odets play about an up-and-coming boxer who also happens to be a talented violinist—a high concept that might strike you as faintly ridiculous, but then maybe you're not old enough to remember Mike Reid who some forty years ago was an all-pro defensive tackle for the Cincinnati Bengals as well as a concert pianist and later a Grammy-winning songwriter who was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2005.

As I keep telling you, there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. So we were there with open minds.

Clifford Odets, as you probably know, was a playwright who had a brief but wildly-successful run on Broadway in the 1930s. He was also one of the founding members of the Group Theater, an influential theater company that introduced "Method" acting to America. His best-known stage work includes Waiting For Lefty, Golden Boy and The Country Girl. After tastes changed on Broadway in the early '40s—or should I say, after Broadway lost its taste for Clifford Odets—he decamped for Hollywood. He famously struggled there, but he did make one lasting contribution, collaborating on the screenplay to Sweet Smell of Success, starring Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster, one of the most biting and cynical movies of the 1950s. He died in 1963.

That the Coen Brothers spoofed Odets in Barton Fink as a pretentious Broadway playwright lacking the talent even for hackwork perhaps should have given me pause before racing up to see what the New Yorker notes is a "rarely revived" play, but what can I tell you—I love the theater, I love free food and, to quote Cole Porter, I happen to like New York.

And when I have to give the world a last farewell,

And the undertaker starts to ring my funeral bell,

I don't want to go to heaven, don't want to go to hell.

I happen to like New York.

After cocktails and hors d'oeuvres at Jeffrey Zakarian's Lambs Club with forty or so of our fellow blog-typing wallflowers—I am as dull and dreary in person as I am fascinating and unforgettable online—Mister Muleboy and I crossed 44th Street to the Belasco, a fully-refurbished turn-of-the-last-century jewel built by the legendary Broadway producer David Belasco. He designed the auditorium to create what he called a "little theater" experience, with three tiers of seats pushed close to the stage to foster an intimacy between the performers and the audience.

Sitting there, I thought it's no wonder that the Belasco has featured so much serious drama over the last century, including such plays as Johnny Belinda, The Song of Bernadette and A Raisin in the Sun, as well as much of the Group Theater's output. Indeed, Golden Boy premiered 75 years ago this month at the Belasco—and I'm thinking that its revival there now is not a coincidence.

This new production of Golden Boy stars Seth Numrich (War Horse) and Yvonne Strahovski (Chuck and Dexter) in the leads, with Tony Shalhoub, Danny Burstein, Ned Eisenberg and Dagmara Dominczyk, among others, in support. Tony winner Bartlett Sher directs.

The play opens in the seedy offices of Tom Moody, a boxing promoter who was once the best in New York, but who, like the rest of the country, has been struggling to make ends meet since the stock market crash of 1929. At his side is his mistress and girl Friday, Lorna Moon. Lorna is a self-described "tramp from Newark" who was plucked by Moody from a life that sounds vaguely like prostitution to live a life that still sounds vaguely like prostitution, only with one client, better clothes and a softer bed.

Moody is trying to figure out how to raise the $5000 necessary for a divorce settlement—the sap genuinely wants to marry Lorna—when into his office and into his life rushes Joe Bonaparte, a brash young punk who claims to be a great boxer in need only of a great manager to hit the big time. When one of the fighters in Moody's stable breaks a hand before that evening's bout, he shoves the kid into the ring and discovers, shock of shocks, he has a potential goldmine within his grasp.

The only problem is, the boy is also a gifted violinist who's afraid of ruining his delicate mitts on another man's chin. And how can you hope to win the title if you won't take your hands out of your pockets?

Enter the girl.

You know how to get men to do what you want them to do, Moody tells her. Get him to fight and we can finally get married. And so she sets out to seduce the kid. The thing is, though, as time passes, she can't quite decide whether she's manipulating the boy or falling in love with him. She's been batted around enough to want the security that Moody represents, but like most of us, still longs for true love.

Despite the complications of the love triangle, though, the central conflict is between Joe and his father, with the violin and Joe's rare talent for playing it—he's won a gold medal and a scholarship—standing in for the decision each of us must make eventually: what do you want out of life?

Joe's tired of being ashamed of his poverty and sees boxing as a shortcut to fame, fast cars and flashy clothes—all the things he's never had and his father, a Zen master who pushes a fruit cart, has never counted as important. His father will support Joe's choice as long as he's passionate about it, but what he sees in the boy suggests to him that it's the soulful beauty of the violin rather than the violent release of the ring that gives him true pleasure. That there's no real money in music, his father tells him, isn't important as long as you have a purpose in your life and a song in your heart.

But a parent can't live his child's life for him, he can only hope that as the boy makes his mistakes, the consequences aren't so permanent and debilitating that they ruin him for good. And therein lies the rub, for the violin requires delicate hands and boxing is the destroyer of hands. That boxing is also the destroyer of minds and souls—as represented by the angry, brain-addled palooka the father meets in act two—only exacerbates his fears.

In a time when, thanks to the internet, it's possible to be both a struggling artist and a capitalist fat cat, the choices presented here might seem a little quaint. Played out, though, as Golden Boy was in 1937, against the backdrop of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe, the choice between the humane and the expedient wasn't a trivial one—the future of civilization hung in the balance.

So what did I think of the play, Mrs. Lincoln?

The acting is top-notch—especially that of Danny Mastrogiorgio as Tom Moody and Tony Shalhoub as the father. Shalhoub you probably remember from Monk, and I imagine he could add warmth and wit to a recitation of the phone book. Mastrogiorgio, who was previously unknown to me, turns a heel into someone you can root for without softening Moody's edges, and it's his performance you can't take your eyes off of. I'll be looking for more of him in the future.

As for the rest of it, the direction is crisp, the staging inventive, the costumes expertly evoke the period. Kudos all around.

The production's flaws lie within the play itself. At times, Odets was so keen to make his points, he seemed to forget his characters were people rather than allegories and plot devices. Lorna, especially, changes tack from scene to scene depending on which direction the story needs go, rendering her motivations not so much complex as murky.

And let me tell you, while complex is exhilarating, murky is frustrating, irritating, and finally enervating—especially by the end of a nearly three hour play.

Still, it's the sort of story that'll stick with you for days, giving you something to mull over rather than forget, and since for a change there was no traffic in the Lincoln Tunnel, I'd call the evening a success—I was home in bed with Katie-Bar-The-Door well before the sun peeked over the horizon.

This being a classic film blog, I was naturally curious afterwards to see how the pros in Hollywood adapted the play to the big screen, and the following morning, I wound up watching the 1939 film adaptation starring Barbara Stanwyck, William Holden and Adolphe Menjou.

It's a more conventional crowd-pleaser, that's for sure.

The girl was already a hop skip and a jump from being a classic Barbara Stanwyck character and Hollywood simply straightened out her through line, turning her into a "dame from Newark" who rediscovers the heart of gold that was always beating in her tastefully slender bosom. Her Lorna is both bitchier and ultimately sweeter than Odets's conception because she, not Moody, is the schemer calling the shots. She's got the boy, her boss and the whole wide world by the balls and she relishes that it's up to her to decide whether and how hard to squeeze.

Like most of Stanwyck's best roles, she's interesting because—right or wrong—she's the one in control.

And how does the film handle Joe Bonaparte?—a pertinent issue since, Mike Reid or no Mike Reid, the choice between the boxing ring and the violin is not and never has been a real world dilemma. William Holden plays him as a tousled-haired schoolboy, twenty-one going on twelve, who nevertheless feels a need to pull his own weight. Music is wonderful, he concedes, but it doesn't put food on the table. The shift in motivation changes the story's central philosophical conflict from an issue of the eternal versus the ephemeral to one of the idealistic versus the practical, a subtle but significant difference.

With Adolphe Menjou playing Moody for laughs, Lee J. Cobb (at age 27!) channeling Chico Marx as William Holden's father, and the supporting cast delivering their lines at twice the speed of normal human speech, the tone is bright and brassy rather than portentous, more Guys and Dolls than Eugene O'Neill.

Does that make the movie better than the play? Well, it's shorter anyway. No doubt the changes were necessary to make the story palatable to an audience that had sacrificed a great deal more than the violin to survive the Great Depression. There's no denying, though, that the movie version of Golden Boy has always been regarded as a minor entry on each of its stars' resumes.

In the final analysis, the film is more a curiosity—a chance to marvel at an impossibly young William Holden eleven years before his breakthrough in Sunset Boulevard—than a necessity. Fit it into your schedule, maybe, after you've run through the best of Holden's (and Stanwyck's) work.

So how about the Broadway revival—can I recommend it to you?

Well, the Ice Capades it isn't, and if you're in town for one night looking for the dramatic equivalent of hot dogs and cotton candy, honestly, you should go elsewhere. But if you're hungry for a deep dish of heavy think in the company of Odets, the Group Theater and the ghosts of Old Broadway, by all means, dive in.

Just don't expect them to spoonfeed it to you.

Golden Boy is currently in previews at the Belasco. It officially opens on December 6 and runs through January 20, 2013. To visit the show's website, click here.

As I keep telling you, there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. So we were there with open minds.

Clifford Odets, as you probably know, was a playwright who had a brief but wildly-successful run on Broadway in the 1930s. He was also one of the founding members of the Group Theater, an influential theater company that introduced "Method" acting to America. His best-known stage work includes Waiting For Lefty, Golden Boy and The Country Girl. After tastes changed on Broadway in the early '40s—or should I say, after Broadway lost its taste for Clifford Odets—he decamped for Hollywood. He famously struggled there, but he did make one lasting contribution, collaborating on the screenplay to Sweet Smell of Success, starring Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster, one of the most biting and cynical movies of the 1950s. He died in 1963.

That the Coen Brothers spoofed Odets in Barton Fink as a pretentious Broadway playwright lacking the talent even for hackwork perhaps should have given me pause before racing up to see what the New Yorker notes is a "rarely revived" play, but what can I tell you—I love the theater, I love free food and, to quote Cole Porter, I happen to like New York.

And when I have to give the world a last farewell,

And the undertaker starts to ring my funeral bell,

I don't want to go to heaven, don't want to go to hell.

I happen to like New York.

After cocktails and hors d'oeuvres at Jeffrey Zakarian's Lambs Club with forty or so of our fellow blog-typing wallflowers—I am as dull and dreary in person as I am fascinating and unforgettable online—Mister Muleboy and I crossed 44th Street to the Belasco, a fully-refurbished turn-of-the-last-century jewel built by the legendary Broadway producer David Belasco. He designed the auditorium to create what he called a "little theater" experience, with three tiers of seats pushed close to the stage to foster an intimacy between the performers and the audience.

Sitting there, I thought it's no wonder that the Belasco has featured so much serious drama over the last century, including such plays as Johnny Belinda, The Song of Bernadette and A Raisin in the Sun, as well as much of the Group Theater's output. Indeed, Golden Boy premiered 75 years ago this month at the Belasco—and I'm thinking that its revival there now is not a coincidence.

This new production of Golden Boy stars Seth Numrich (War Horse) and Yvonne Strahovski (Chuck and Dexter) in the leads, with Tony Shalhoub, Danny Burstein, Ned Eisenberg and Dagmara Dominczyk, among others, in support. Tony winner Bartlett Sher directs.

The play opens in the seedy offices of Tom Moody, a boxing promoter who was once the best in New York, but who, like the rest of the country, has been struggling to make ends meet since the stock market crash of 1929. At his side is his mistress and girl Friday, Lorna Moon. Lorna is a self-described "tramp from Newark" who was plucked by Moody from a life that sounds vaguely like prostitution to live a life that still sounds vaguely like prostitution, only with one client, better clothes and a softer bed.

Moody is trying to figure out how to raise the $5000 necessary for a divorce settlement—the sap genuinely wants to marry Lorna—when into his office and into his life rushes Joe Bonaparte, a brash young punk who claims to be a great boxer in need only of a great manager to hit the big time. When one of the fighters in Moody's stable breaks a hand before that evening's bout, he shoves the kid into the ring and discovers, shock of shocks, he has a potential goldmine within his grasp.

The only problem is, the boy is also a gifted violinist who's afraid of ruining his delicate mitts on another man's chin. And how can you hope to win the title if you won't take your hands out of your pockets?

Enter the girl.

You know how to get men to do what you want them to do, Moody tells her. Get him to fight and we can finally get married. And so she sets out to seduce the kid. The thing is, though, as time passes, she can't quite decide whether she's manipulating the boy or falling in love with him. She's been batted around enough to want the security that Moody represents, but like most of us, still longs for true love.

Despite the complications of the love triangle, though, the central conflict is between Joe and his father, with the violin and Joe's rare talent for playing it—he's won a gold medal and a scholarship—standing in for the decision each of us must make eventually: what do you want out of life?

Joe's tired of being ashamed of his poverty and sees boxing as a shortcut to fame, fast cars and flashy clothes—all the things he's never had and his father, a Zen master who pushes a fruit cart, has never counted as important. His father will support Joe's choice as long as he's passionate about it, but what he sees in the boy suggests to him that it's the soulful beauty of the violin rather than the violent release of the ring that gives him true pleasure. That there's no real money in music, his father tells him, isn't important as long as you have a purpose in your life and a song in your heart.

But a parent can't live his child's life for him, he can only hope that as the boy makes his mistakes, the consequences aren't so permanent and debilitating that they ruin him for good. And therein lies the rub, for the violin requires delicate hands and boxing is the destroyer of hands. That boxing is also the destroyer of minds and souls—as represented by the angry, brain-addled palooka the father meets in act two—only exacerbates his fears.

In a time when, thanks to the internet, it's possible to be both a struggling artist and a capitalist fat cat, the choices presented here might seem a little quaint. Played out, though, as Golden Boy was in 1937, against the backdrop of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe, the choice between the humane and the expedient wasn't a trivial one—the future of civilization hung in the balance.

So what did I think of the play, Mrs. Lincoln?

The acting is top-notch—especially that of Danny Mastrogiorgio as Tom Moody and Tony Shalhoub as the father. Shalhoub you probably remember from Monk, and I imagine he could add warmth and wit to a recitation of the phone book. Mastrogiorgio, who was previously unknown to me, turns a heel into someone you can root for without softening Moody's edges, and it's his performance you can't take your eyes off of. I'll be looking for more of him in the future.

As for the rest of it, the direction is crisp, the staging inventive, the costumes expertly evoke the period. Kudos all around.

The production's flaws lie within the play itself. At times, Odets was so keen to make his points, he seemed to forget his characters were people rather than allegories and plot devices. Lorna, especially, changes tack from scene to scene depending on which direction the story needs go, rendering her motivations not so much complex as murky.

And let me tell you, while complex is exhilarating, murky is frustrating, irritating, and finally enervating—especially by the end of a nearly three hour play.

Still, it's the sort of story that'll stick with you for days, giving you something to mull over rather than forget, and since for a change there was no traffic in the Lincoln Tunnel, I'd call the evening a success—I was home in bed with Katie-Bar-The-Door well before the sun peeked over the horizon.

This being a classic film blog, I was naturally curious afterwards to see how the pros in Hollywood adapted the play to the big screen, and the following morning, I wound up watching the 1939 film adaptation starring Barbara Stanwyck, William Holden and Adolphe Menjou.

It's a more conventional crowd-pleaser, that's for sure.

The girl was already a hop skip and a jump from being a classic Barbara Stanwyck character and Hollywood simply straightened out her through line, turning her into a "dame from Newark" who rediscovers the heart of gold that was always beating in her tastefully slender bosom. Her Lorna is both bitchier and ultimately sweeter than Odets's conception because she, not Moody, is the schemer calling the shots. She's got the boy, her boss and the whole wide world by the balls and she relishes that it's up to her to decide whether and how hard to squeeze.

Like most of Stanwyck's best roles, she's interesting because—right or wrong—she's the one in control.

And how does the film handle Joe Bonaparte?—a pertinent issue since, Mike Reid or no Mike Reid, the choice between the boxing ring and the violin is not and never has been a real world dilemma. William Holden plays him as a tousled-haired schoolboy, twenty-one going on twelve, who nevertheless feels a need to pull his own weight. Music is wonderful, he concedes, but it doesn't put food on the table. The shift in motivation changes the story's central philosophical conflict from an issue of the eternal versus the ephemeral to one of the idealistic versus the practical, a subtle but significant difference.

With Adolphe Menjou playing Moody for laughs, Lee J. Cobb (at age 27!) channeling Chico Marx as William Holden's father, and the supporting cast delivering their lines at twice the speed of normal human speech, the tone is bright and brassy rather than portentous, more Guys and Dolls than Eugene O'Neill.

Does that make the movie better than the play? Well, it's shorter anyway. No doubt the changes were necessary to make the story palatable to an audience that had sacrificed a great deal more than the violin to survive the Great Depression. There's no denying, though, that the movie version of Golden Boy has always been regarded as a minor entry on each of its stars' resumes.

In the final analysis, the film is more a curiosity—a chance to marvel at an impossibly young William Holden eleven years before his breakthrough in Sunset Boulevard—than a necessity. Fit it into your schedule, maybe, after you've run through the best of Holden's (and Stanwyck's) work.

So how about the Broadway revival—can I recommend it to you?

Well, the Ice Capades it isn't, and if you're in town for one night looking for the dramatic equivalent of hot dogs and cotton candy, honestly, you should go elsewhere. But if you're hungry for a deep dish of heavy think in the company of Odets, the Group Theater and the ghosts of Old Broadway, by all means, dive in.

Just don't expect them to spoonfeed it to you.

Golden Boy is currently in previews at the Belasco. It officially opens on December 6 and runs through January 20, 2013. To visit the show's website, click here.

Thursday, February 16, 2012

The Katie-Bar-The-Door Awards (1969)

Some stray thoughts for future essays about a few of the Katie winners of 1969:

The Wild Bunch

I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted in their youth has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it.

I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted in their youth has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it.

But as Dylan Thomas pointed out, there's more than one way to grow old: you can go quietly into the night, or you can rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Pike chooses to rage. And oh how he rages.

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie

Just because someone is bright and pretty and charismatic doesn't mean she's not also an idiot. Jean Brodie (Maggie Smith in an Oscar-winning turn) is a beloved teacher in the Dead Poets Society mold, but what to me often seems lost in reviews and recollections of the part is that Miss Brodie is also a self-righteous nincompoop, prone to pronouncements such as "Whoever has opened the window has opened it too wide. Six inches is perfectly adequate—more is vulgar."

Just because someone is bright and pretty and charismatic doesn't mean she's not also an idiot. Jean Brodie (Maggie Smith in an Oscar-winning turn) is a beloved teacher in the Dead Poets Society mold, but what to me often seems lost in reviews and recollections of the part is that Miss Brodie is also a self-righteous nincompoop, prone to pronouncements such as "Whoever has opened the window has opened it too wide. Six inches is perfectly adequate—more is vulgar."

She no doubt makes similar pronouncements to her married lover.

For Miss Jean Brodie, teaching isn't so much about preparing her students for the world as it is about creating a classroom full of Jean Brodie clones, little girls who demand nothing of her but to worship the ground she walks on. As for Brodie, she worships Italian poets and Italian painters—and Italian fascists, too—and even if those arrayed against her are a stiff-necked and detestable lot, it seems unlikely to me that anyone could (or would) write a story in the 1960s about a character who tells you how admirable Mussolini is without assuming that you understand the character is more than a bit cracked. That's something to remember—the enemy of your enemy is just as likely to turn out to be your enemy as your friend, so don't assume that just because you don't like the headmistress (Celia Johnson) that Miss Brodie isn't also (if differently) wrong-headed.

As I said in my post about Chimes at Midnight, "A fool who is unaware he is a fool is a ripe subject for comedy." Jean Brodie is just such a fool. That she's also a sympathetic one, you can credit Maggie Smith for that.

[If you're interested in a more in-depth look at The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, FlickChick wrote a nice review of it only yesterday over at A Person in the Dark. Click here to read it.]

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

I probably don't need to tell you that Sean Connery was the definitive James Bond. The first four Bond films, Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger and even Thunderball are all classics, never bettered.

I probably don't need to tell you that Sean Connery was the definitive James Bond. The first four Bond films, Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger and even Thunderball are all classics, never bettered.

But the dirty little secret about Sean Connery is that by You Only Live Twice, the Bond film immediately preceding this one, he was phoning it in, and he was no better in Diamonds Are Forever, the film after this one.

And I'll tell you something else. Despite his rugged good looks, Connery really was not a very good romantic lead, not in a classic sense anyway. He was best when he was aloof, amused, snarky or, as he was in roles such as The Untouchables, wounded, brooding and angry. Romance requires a combination of hope and vulnerability, a rare quality in gods, which may explain why good-looking leading men such as George Clooney and Brad Pitt are inexplicably not great romantic leading men.

This is heresy to say, but for this one movie, where Bond genuinely falls in love, George Lazenby was probably better suited to the role than Connery.

Crikey, I can't believe I just said that out loud. True, though.

PICTURE (Drama)

winner: The Wild Bunch (prod. Phil Feldman)

nominees: Easy Rider (prod. Peter Fonda); Medium Cool (prod. Tully Friedman, Haskell Wexler and Jerrold Wexler); Midnight Cowboy (prod. Jerome Hellman); On Her Majesty's Secret Service (prod. Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman); They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (prod. Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler)

PICTURE (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (prod. John Foreman)

nominees: The Italian Job (prod. Michael Deeley); Oh! What a Lovely War (prod. Richard Attenborough and Brian Duffy); The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (prod. Robert Fryer); Support Your Local Sheriff! (prod. William Bowers); Take The Money and Run (prod. Charles H. Joffe)

PICTURE (Foreign Language)

winner: Z (prod. Jacques Perrin and Ahmed Rachedi)

nominees: L'armée des ombres (Army of Shadows) (prod. Jacques Dorfmann); Le chagrin et la pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity) (prod. André Harris and Alain de Sedouy); Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's) (prod. Pierre Cottrell and Barbet Schroeder)

ACTOR (Drama)

winner: William Holden (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: Peter Fonda (Easy Rider); Dustin Hoffman (Midnight Cowboy); Jon Voight (Midnight Cowboy); John Wayne (True Grit)

ACTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: James Garner (Support Your Local Sheriff)

nominees: Woody Allen (Take the Money and Run); Michael Caine (The Italian Job); Dustin Hoffman (John and Mary); Paul Newman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Robert Redford (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid)

ACTRESS (Drama)

winner: Shirley Knight (The Rain People)

nominees: Genevieve Bujold (Anne of the Thousand Days); Jane Fonda (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); Liv Ullmann (En Passion a.k.a. The Passion of Anna)

ACTRESS (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Maggie Smith (The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie)

nominees: Mia Farrow (John and Mary); Shirley MacLaine (Sweet Charity); Liza Minnelli (The Sterile Cuckoo); Katharine Ross (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Barbara Streisand (Hello, Dolly!)

DIRECTOR (Drama)

winner: Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: Costa-Gavras (Z); Jean-Pierre Melville (L'armée des ombres a.k.a. Army of Shadows); Marcel Ophüls (Le chagrin et la pitié a.k.a. The Sorrow and the Pity); Sydney Pollack (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); John Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy); Haskell Wexler (Medium Cool)

DIRECTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: George Roy Hill (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid)

nominees: Woody Allen (Take the Money and Run); Richard Attenborough (Oh! What a Lovely War); Ronald Neame (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie)

SUPPORTING ACTOR

winner: Jack Nicholson (Easy Rider)

nominees: Red Buttons (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); John Mills (Oh! What a Lovely War); Robert Ryan (The Wild Bunch); Gig Young (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?)

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

winner: Diana Rigg (On Her Majesty's Secret Service)

nominees: Bibi Andersson (En Passion a.k.a. The Passion of Anna); Dyan Cannon (Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice); Pamela Franklin (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie); Celia Johnson (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie); Simone Signoret (L'armée des ombres a.k.a. Army of Shadows); Suzannah York (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?)

SCREENPLAY

winner: Walon Green and Sam Peckinpah, story by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Jorge Semprún, from a novel by Vasilis Vasilikos (Z)

SPECIAL AWARDS

"Rain Drops Keep Fallin' on My Head" (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) music by Burt Bacharach; lyrics by Hal David (Score); Louis Lombardo (The Wild Bunch) (Film Editing); Le chagrin et la pitié a.k.a. The Sorrow and the Pity (Documentary Feature)

The Wild Bunch

I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted in their youth has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it.

I don't know anybody over the age of fifty who isn't a little startled, dismayed and embarrassed to realize that the upward trajectory of the life that they so took for granted in their youth has nosed over and is now on a permanent downward spiral toward the grave. For Pike Bishop (William Holden), the aging leader of a gang of Old West desperados, it's not just that he no longer understands the world that has changed around him; it's the realization that even if he did understand it, he no longer has the energy, stamina or reflexes to do anything about it.But as Dylan Thomas pointed out, there's more than one way to grow old: you can go quietly into the night, or you can rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Pike chooses to rage. And oh how he rages.

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie

Just because someone is bright and pretty and charismatic doesn't mean she's not also an idiot. Jean Brodie (Maggie Smith in an Oscar-winning turn) is a beloved teacher in the Dead Poets Society mold, but what to me often seems lost in reviews and recollections of the part is that Miss Brodie is also a self-righteous nincompoop, prone to pronouncements such as "Whoever has opened the window has opened it too wide. Six inches is perfectly adequate—more is vulgar."

Just because someone is bright and pretty and charismatic doesn't mean she's not also an idiot. Jean Brodie (Maggie Smith in an Oscar-winning turn) is a beloved teacher in the Dead Poets Society mold, but what to me often seems lost in reviews and recollections of the part is that Miss Brodie is also a self-righteous nincompoop, prone to pronouncements such as "Whoever has opened the window has opened it too wide. Six inches is perfectly adequate—more is vulgar."She no doubt makes similar pronouncements to her married lover.

For Miss Jean Brodie, teaching isn't so much about preparing her students for the world as it is about creating a classroom full of Jean Brodie clones, little girls who demand nothing of her but to worship the ground she walks on. As for Brodie, she worships Italian poets and Italian painters—and Italian fascists, too—and even if those arrayed against her are a stiff-necked and detestable lot, it seems unlikely to me that anyone could (or would) write a story in the 1960s about a character who tells you how admirable Mussolini is without assuming that you understand the character is more than a bit cracked. That's something to remember—the enemy of your enemy is just as likely to turn out to be your enemy as your friend, so don't assume that just because you don't like the headmistress (Celia Johnson) that Miss Brodie isn't also (if differently) wrong-headed.

As I said in my post about Chimes at Midnight, "A fool who is unaware he is a fool is a ripe subject for comedy." Jean Brodie is just such a fool. That she's also a sympathetic one, you can credit Maggie Smith for that.

[If you're interested in a more in-depth look at The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, FlickChick wrote a nice review of it only yesterday over at A Person in the Dark. Click here to read it.]

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

I probably don't need to tell you that Sean Connery was the definitive James Bond. The first four Bond films, Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger and even Thunderball are all classics, never bettered.

I probably don't need to tell you that Sean Connery was the definitive James Bond. The first four Bond films, Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger and even Thunderball are all classics, never bettered.But the dirty little secret about Sean Connery is that by You Only Live Twice, the Bond film immediately preceding this one, he was phoning it in, and he was no better in Diamonds Are Forever, the film after this one.

And I'll tell you something else. Despite his rugged good looks, Connery really was not a very good romantic lead, not in a classic sense anyway. He was best when he was aloof, amused, snarky or, as he was in roles such as The Untouchables, wounded, brooding and angry. Romance requires a combination of hope and vulnerability, a rare quality in gods, which may explain why good-looking leading men such as George Clooney and Brad Pitt are inexplicably not great romantic leading men.

This is heresy to say, but for this one movie, where Bond genuinely falls in love, George Lazenby was probably better suited to the role than Connery.

Crikey, I can't believe I just said that out loud. True, though.

PICTURE (Drama)

winner: The Wild Bunch (prod. Phil Feldman)

nominees: Easy Rider (prod. Peter Fonda); Medium Cool (prod. Tully Friedman, Haskell Wexler and Jerrold Wexler); Midnight Cowboy (prod. Jerome Hellman); On Her Majesty's Secret Service (prod. Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman); They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (prod. Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler)

PICTURE (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (prod. John Foreman)

nominees: The Italian Job (prod. Michael Deeley); Oh! What a Lovely War (prod. Richard Attenborough and Brian Duffy); The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (prod. Robert Fryer); Support Your Local Sheriff! (prod. William Bowers); Take The Money and Run (prod. Charles H. Joffe)

PICTURE (Foreign Language)

winner: Z (prod. Jacques Perrin and Ahmed Rachedi)

nominees: L'armée des ombres (Army of Shadows) (prod. Jacques Dorfmann); Le chagrin et la pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity) (prod. André Harris and Alain de Sedouy); Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's) (prod. Pierre Cottrell and Barbet Schroeder)

ACTOR (Drama)

winner: William Holden (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: Peter Fonda (Easy Rider); Dustin Hoffman (Midnight Cowboy); Jon Voight (Midnight Cowboy); John Wayne (True Grit)

ACTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: James Garner (Support Your Local Sheriff)

nominees: Woody Allen (Take the Money and Run); Michael Caine (The Italian Job); Dustin Hoffman (John and Mary); Paul Newman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Robert Redford (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid)

ACTRESS (Drama)

winner: Shirley Knight (The Rain People)

nominees: Genevieve Bujold (Anne of the Thousand Days); Jane Fonda (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); Liv Ullmann (En Passion a.k.a. The Passion of Anna)

ACTRESS (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Maggie Smith (The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie)

nominees: Mia Farrow (John and Mary); Shirley MacLaine (Sweet Charity); Liza Minnelli (The Sterile Cuckoo); Katharine Ross (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Barbara Streisand (Hello, Dolly!)

DIRECTOR (Drama)

winner: Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: Costa-Gavras (Z); Jean-Pierre Melville (L'armée des ombres a.k.a. Army of Shadows); Marcel Ophüls (Le chagrin et la pitié a.k.a. The Sorrow and the Pity); Sydney Pollack (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); John Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy); Haskell Wexler (Medium Cool)

DIRECTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: George Roy Hill (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid)

nominees: Woody Allen (Take the Money and Run); Richard Attenborough (Oh! What a Lovely War); Ronald Neame (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie)

SUPPORTING ACTOR

winner: Jack Nicholson (Easy Rider)

nominees: Red Buttons (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?); John Mills (Oh! What a Lovely War); Robert Ryan (The Wild Bunch); Gig Young (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?)

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

winner: Diana Rigg (On Her Majesty's Secret Service)

nominees: Bibi Andersson (En Passion a.k.a. The Passion of Anna); Dyan Cannon (Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice); Pamela Franklin (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie); Celia Johnson (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie); Simone Signoret (L'armée des ombres a.k.a. Army of Shadows); Suzannah York (They Shoot Horses, Don't They?)

SCREENPLAY

winner: Walon Green and Sam Peckinpah, story by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner (The Wild Bunch)

nominees: William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); Jorge Semprún, from a novel by Vasilis Vasilikos (Z)

SPECIAL AWARDS

"Rain Drops Keep Fallin' on My Head" (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) music by Burt Bacharach; lyrics by Hal David (Score); Louis Lombardo (The Wild Bunch) (Film Editing); Le chagrin et la pitié a.k.a. The Sorrow and the Pity (Documentary Feature)

Saturday, January 28, 2012

The Katie-Bar-The-Door Awards (1950)

Spencer Tracy's performance in Father of the Bride is one of those that looks effortless until you start thinking of all the ways it could have gone wrong. The film's producers initially talked of casting Jack Benny, which on the surface makes sense—he was one of the most popular entertainers in America and he was famous for playing cheapskates:

Spencer Tracy's performance in Father of the Bride is one of those that looks effortless until you start thinking of all the ways it could have gone wrong. The film's producers initially talked of casting Jack Benny, which on the surface makes sense—he was one of the most popular entertainers in America and he was famous for playing cheapskates:"Your money or your life!"

"I'm thinking, I'm thinking!"

But Benny in the title role would have very quickly become a one-note joke—he's cheap, we get it.

And then there's the remake with Steve Martin, a very fine comic actor, but boy, was he a disaster in this part. His relationship to his daughter isn't touching, it's creepy, bordering on the incestuous. Not to mention I did the math in my head while I was sitting in the theater watching this some twenty-plus years ago (good lord, when did I get to be this old?) and I realized the wedding was costing him something like $125,000—those are 1991 dollars, mind you—a ridiculous amount of money. That Martin was unable to make his objections to this runaway insanity seem even remotely reasonable is an indictment of both him and the remake's writers.

With apparent ease, Tracy steered his performance away from all these potential disasters, and in the process, makes us feel sympathy for him—the money, the loss of his "little girl"—even as we laugh at his foibles.

With apparent ease, Tracy steered his performance away from all these potential disasters, and in the process, makes us feel sympathy for him—the money, the loss of his "little girl"—even as we laugh at his foibles.It's another movie, perhaps as in all of his movies, where you're tempted to say, "He's not really acting, he's just playing himself." Except that when you see his top six or eight movies—Fury, Libeled Lady, Captains Courageous, Woman of the Year, Adam's Rib, Bad Day at Black Rock—and compare them to each other, you realize he's covered a lot of ground. What he consistently does is find the core of humanity in his character, no mean trick, I think.

PICTURE (Drama)

winner: Sunset Boulevard (prod. Charles Brackett)

nominees: All About Eve (prod. Darryl F. Zanuck); The Asphalt Jungle (prod. Arthur Hornblow, Jr.); Gun Crazy (prod. Frank King and Maurice King); The Gunfighter (prod. Nunnally Johnson); In A Lonely Place (prod. Robert Lord); Night and the City (prod. Samuel G. Engel); Wagon Master (prod. Merian C. Cooper and John Ford); Winchester '73 (prod. Aaron Rosenberg)

PICTURE (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Harvey (prod. John Beck)

nominees: Born Yesterday (prod. S. Sylvan Simon); Cinderella (prod. Walt Disney)

PICTURE (Foreign Language)

winner: Rashômon (prod. Minoru Jingo )

nominees: Los olvidados (prod. Óscar Dancigers, Sergio Kogan and Jaime A. Menasce); Orphée (Orpheus) (prod. André Paulvé); La Ronde (prod. Ralph Baum and Sacha Gordine)

ACTOR (Drama)

winner: William Holden (Sunset Boulevard)

nominees: Dana Andrews (Where The Sidewalk Ends); Humphrey Bogart (In A Lonely Place); Marlon Brando (The Men); José Ferrer (Cyrano de Bergerac); John Garfield (The Breaking Point); Stewart Granger (King Solomon's Mines); Gregory Peck (The Gunfighter); James Stewart (Winchester '73); Richard Widmark (Night and the City, Panic in the Streets and No Way Out)

ACTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Spencer Tracy (Father Of The Bride)

nominees: Ronald Colman (Champagne For Caesar); Broderick Crawford (Born Yesterday); James Stewart (Harvey); Clifton Webb (Cheaper By The Dozen)

ACTRESS (Drama)

winner: Gloria Swanson (Sunset Boulevard)

nominees: Anne Baxter (All About Eve); Peggy Cummins (Gun Crazy); Bette Davis (All About Eve); Gloria Grahame (In A Lonely Place); Eleanor Parker (Caged)

ACTRESS (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Judy Holliday (Born Yesterday)

nominees: Joan Bennett (Father Of The Bride); Betty Hutton (Annie Get Your Gun)

DIRECTOR (Drama)

winner: Akira Kurosawa (Rashômon)

nominees: Luis Buñuel (Los olividados); Jean Cocteau (Orphée a.k.a. Orpheus); Jules Dassin (Night and the City); John Huston (The Asphalt Jungle); Joseph H. Lewis (Gun Crazy); Joseph L. Mankiewicz (All About Eve); Anthony Mann (Winchester '73); Nicholas Ray (In A Lonely Place); Billy Wilder (Sunset Boulevard)

DIRECTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Henry Koster (Harvey)

nominees: George Cukor (Born Yesterday); Vincente Minnelli (Father Of The Bride); George Sidney (Annie Get Your Gun)

SUPPORTING ACTOR

winner: George Sanders (All About Eve)

nominees: Louis Calhern (The Asphalt Jungle); Sam Jaffe (The Asphalt Jungle); Toshirô Mifune (Rashômon); Erich von Stroheim (Sunset Boulevard)

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

winner: Celeste Holm (All About Eve)

nominees: Jean Hagen (The Asphalt Jungle); Josephine Hull (Harvey); Machiko Kyo (Rashômon); Marilyn Monroe (The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve); Nancy Olson (Sunset Boulevard); Thelma Ritter (All About Eve)

SCREENPLAY

winner: Joseph L. Mankiewicz, from the story "The Wisdom of Eve" by Mary Orr (All About Eve)

nominees: Mary Chase and Oscar Brodney, from the play by Mary Chase (Harvey); Akira Kurosawa and Shinobu Hashimoto, from the stories "Rashômon" and "In A Grove" by Ryûnosuke Akutagawa (Rashômon); Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder and D.M. Marshman, Jr. (Sunset Boulevard)

SPECIAL AWARDS

Hans Dreier, John Meehan, Sam Comer and Ray Moyer (Sunset Boulevard) (Art Direction-Set Decoration); Russell Harlan (Gun Crazy) (Cinematography)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)