If you haven't seen it, Gravity is the story of an astronaut (Sandra Bullock) who is marooned in space after a catastrophe destroys her ship and kills her crewmates. Armed with nothing but her wits, a spacesuit and the oxygen on her back, she makes one harrowing leap after another into the unknown, searching for a way home before she runs out of air or burns up in the atmosphere.

That's the plot.

What it's about, though, is a woman who's been marking time since the death of her daughter, drowning in a pool of grief she can't escape. Sure, she's still active — she's an astronaut, fer Chrissake! — but she's going through the motions. Now, however, thanks to circumstances beyond her control, she has to make a choice whether she's going to get on with her life or join her daughter in the great beyond.

If you did this same story starring a woman sitting in a silent room with a ticking clock, the critics would lap it up with a spoon, but nobody would watch it. Put her in a spacesuit and play out her therapy while she's gasping for oxygen? Now you've got something.

It's like that show from a while back about a middle-aged man with mother issues who pours out his soul to his psychiatrist every week. Pretty dull stuff, right? But make him a gangster, call him Tony Soprano? The rest is television history.

All the great ones — Chaplin, Ford, Hawks, Wilder, Hitchcock, Spielberg, Tarantino, Gerwig — knew how to wrap a tasty doggie treat around the bitter pill of truth they were feeding you.

The late great Stanley Kubrick — who was absolutely never accused by anyone of being a corporate shill — once had this to say about the practical need to put the "popular" in "popular entertainment":

"However serious your intentions may be, and however important you think are the ideas of the story, the enormous cost of a movie makes it necessary to reach the largest potential audience for that story, in order to give your backers their best chance to get their money back and hopefully make a profit. No one will disagree that a good story is an essential starting point for accomplishing this. But another thing, too, the stronger the story, the more chances you can take with everything else."

Remember that the next time you're tempted to dismiss something as "merely" entertaining. Entertaining is what puts butts in the seats and make everything else possible.

My choices are noted with a ★. A tie is indicated with a ✪. Historical Oscar winners are noted with a ✔. Best foreign-language picture winners are noted with an ƒ. Best animated feature winners are noted with an @. A historical winner who won in a different category is noted with a ✱.

Showing posts with label Science Fiction. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Science Fiction. Show all posts

Sunday, November 10, 2024

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

Blade Runner 2049: I Want More Life, F#cker

Director Denis Villeneuve takes a ninety-minute butterfly and pins its wings to a nearly three-hour running time. All the flaws of the original — minimalist storytelling, elegiac tempo — with none of the magic that made the original a classic.

I suspect even the people most closely involved with 1982's Blade Runner don't know why it worked so well.

I suspect even the people most closely involved with 1982's Blade Runner don't know why it worked so well.

Thursday, January 7, 2016

Too, Too Funny

Sometimes you read a satire so biting, you just have to share it. To wit, from Richard Brody's movie column in the January 6, 2016 New Yorker:

What endures for the critics and their lay associates, for aesthetes who live for the beauty and the pleasure of movies, is [George] Lucas’s directing—of two films, “Attack of the Clones” and, especially, “Revenge of the Sith.” If Lucas had done nothing else in his life, he’d have an honored place in my personal pantheon for that work.

HAHAHAHAHAHA!!!! Hilarious! Droll! Well-played, sir!

Oh, wait, I think he's serious ...

After twenty years, Katie-Bar-The-Door and I are letting our subscription to the New Yorker magazine lapse. Richard Brody's comments about George Lucas have nothing to do with it, but close enough.

By the way, we very much enjoyed the new Star Wars film, The Force Awakens. It's fun the way they used to be fun nearly forty years ago now. That there are people, including George Lucas himself, who don't like it for that very reason is explanation enough for how the franchise ran seriously off the rails in the dismal prequel years.

What endures for the critics and their lay associates, for aesthetes who live for the beauty and the pleasure of movies, is [George] Lucas’s directing—of two films, “Attack of the Clones” and, especially, “Revenge of the Sith.” If Lucas had done nothing else in his life, he’d have an honored place in my personal pantheon for that work.

HAHAHAHAHAHA!!!! Hilarious! Droll! Well-played, sir!

Oh, wait, I think he's serious ...

After twenty years, Katie-Bar-The-Door and I are letting our subscription to the New Yorker magazine lapse. Richard Brody's comments about George Lucas have nothing to do with it, but close enough.

By the way, we very much enjoyed the new Star Wars film, The Force Awakens. It's fun the way they used to be fun nearly forty years ago now. That there are people, including George Lucas himself, who don't like it for that very reason is explanation enough for how the franchise ran seriously off the rails in the dismal prequel years.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

TV's Lost in Space, Part 4: The 50th Anniversary — What To Watch

It was fifty years ago today that Lost in Space made its television premiere on CBS, and in a year chock-full of momentous events — the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the march on Selma, the assassination of Malcolm X, the establishment of Medicare, and lots of great new Beatles music — the premiere of Lost in Space was probably the most memorable.

Or at least it's the one I'm writing about.

I didn't see the premiere — my devotion to the show began during its first years of syndication, about five years later — but still, pretty exciting.

And at last, all 84 episodes of Lost in Space are available on Blu-Ray, fully-restored and remastered with documentaries, interviews, a cast read-through of Bill Mumy's reunion script, and much, much more. Heee wackity do!

I assume most of you pre-ordered your set and are ripping the cellophane off the packaging even as you're reading this, planning to watch the entire series in single three-day marathon sitting. And who can blame you? But for the rest of you, maybe you don't know the series that well or — is it possible? — have never seen it at all, and would prefer to dip your toe into the shallow end of the pool, watching a few select episodes for free (with limited commercial interruption) on Hulu.

Whatever your plans, here's a list that might help you decide where to start (click on the title to watch the episode):

THE ORIGIN STORY "MINISERIES"

Not really a miniseries, of course, but interconnected chapters of one storyline, these five episodes take us from the initial liftoff through the family's first few months on an uncharted planet. Along the way, you'll discover how the Robinsons got lost in the first place, how they reacted to their first close encounter with an alien species, and how the show's best known characters, the villainous Dr. Smith and his odd-couple sidekick, the Robot, came to be on board. Featuring all the best set pieces from the unaired pilot, if you're new to the series or just looking to skim the cream off the top, this is a good place to start.

The Reluctant Stowaway

The Derelict

Island in the Sky

There Were Giants in the Earth

The Hungry Sea

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

My Friend, Mr. Nobody — A rare episode that centers on Penny (Angela Cartwright), this is a poignant fairy tale about a lonely little girl and her not-so-imaginary imaginary friend. The sort of thing Rod Serling and The Twilight Zone excelled at.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

Wish Upon a Star — Filled with the first season's signature elements, this is a top-notch morality tale about the dangers of getting everything you want, featuring wonderfully weird expressionistic cinematography, unexplained alien artifacts, the harsh reality of frontier living and Dr. Smith's self-absorbed jack-ass-ery.

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

The Space Croppers — A family of shiftless space hillbillies (led by Oscar-winner Mercedes McCambridge) cultivate a carnivorous crop that threatens to devour the Robinsons. This was the series' first full-blown foray into WTF. It wouldn't be the last.

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

The Prisoners of Space — In this, the best episode of the worst season, a menagerie of alien creatures put the Robinsons on trial for violating the laws of outer space. Kafka with monsters.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

Revolt of the Androids — A couple of androids drop in on the Robinsons, Dr. Smith hatches a get-rich-quick scheme, and human sentimentality wins the day. This one did at least spawn the catchphrase "Crush! Kill! Destroy!"

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

The Questing Beast — So many to choose from, among them "The Space Vikings", "Mutiny in Space", "Curse of Cousin Smith", etc. Here, Penny befriends a papier-mâché dragon that is being hunted by a bumbling knight in King Arthur's armor. How can something so campy be so boring?

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

The Anti-Matter Man — An experiment gone wrong transports Professor Robinson into a parallel dimension where he meets his own evil self. The scenery is summer stock by way of Dr. Caligari, and Guy Williams, having the most fun as an actor since Zorro, gets to chew on all of it. Great stuff, and for those philistines among you who won't touch black-and-white, the best of the color episodes.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

Visit to a Hostile Planet — Season three was wildly uneven, but at least it was trying, leavening genuine science fiction with campy comedy. Here, the Robinsons finally make it back to Earth only to discover it's 1947 and everyone thinks they're hostile, alien invaders. A cross between Star Trek and Dad's Army. Good stuff.

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

The Great Vegetable Rebellion — Featuring a giant talking carrot played by Stanley Adams (Cyrano Jones of Star Trek's "The Trouble with Tribbles"), this is, in the words of Bill Mumy, "probably the worst television show in primetime ever made." So bad, it's good, this is gloriously awful must-see tv.

BEST GUY WILLIAMS (PROF. ROBINSON) EPISODE

Follow the Leader — The spirit of a dead alien warrior possesses Professor Robinson and turns this warm, rational man into a vicious, unpredictable bastard. Dark, moody, occasionally terrifying, pop-culture critic John Kenneth Muir called this episode a parable of "alcoholism in the nuclear family." One of the series' very best.

BEST JUNE LOCKHART (MAUREEN) EPISODE

One of Our Dogs Is Missing — Although set in 1997, the show usually ignored the fact that Betty Friedan was already a household name by 1965, but here June Lockhart gets to show her chops when Maureen is left in charge of the ship while the men are away. Threats abound and she handles them all with brains, bravery and quiet resolve.

BEST MARK GODDARD (MAJOR WEST) EPISODE

Condemned of Space — I've already mentioned "The Hungry Sea" and "The Anti-Matter Man", so I'll go with this one where the Robinsons are captured by a prison spaceship and Major West winds up hanging by his thumbs on an electronic rack. Admittedly, he had more lines in "The Space Primevals" and "Fugitives in Space", but both of those episodes suck. With Marcel Hillaire as a charming murderer who strangles his victims with a string of pearls.

BEST MARTA KRISTEN (JUDY) EPISODE

Attack of the Monster Plants — As daughter Judy, Marta Kristen rarely got a chance to shine but here she showed off a saucy bite as her own evil doppelgänger. Like much of season one, there's a dream-like quality to the mood and cinematography that papers over some of the episode's nuttier flights of fancy.

BEST BILL MUMY (WILL) EPISODE

A Change of Space — As the series' true hero, there are a lot of Will-centered episodes to choose from — "Return from Outer Space", "The Challenge", "Space Creature", among others — but I'll go with this one in which Will takes a ride in an alien space ship and winds up with the most brilliant mind in the galaxy. And still his father doesn't take him seriously! This is one of those episodes that underscores my contention that not all of the trouble Will found himself in was of Dr. Smith's making.

BEST ANGELA CARTWRIGHT (PENNY) EPISODE

The Magic Mirror — Well, the second best, and like the previously-mentioned "My Friend, Mr. Nobody", this is a poignant fairy tale about coming of age on the final frontier. Here, Penny falls through a magic mirror into a dimension with a population of one — a boy (Michael J. Pollard) who promises she'll never have to grow up. Beautiful and bittersweet.

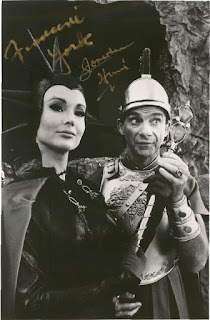

BEST JONATHAN HARRIS (DR. SMITH) EPISODE

Time Merchant — Let's be honest, from best to worst, they were all Dr. Smith episodes. Originally, I planned to pick the episode where Smith isn't a colossal dick, but it turns out there isn't one, so instead I went with this one, an inventive and visually-Daliesque time travel story that poses the question, "What if Smith hadn't been on the show in the first place?"

BEST ROBOT EPISODE

War of the Robots — The first episode where the Robot crosses over from a mere machine, no matter how clever, into a fully-conscious Turing-Test artificial intelligence. Featuring Forbidden Planet's Robby the Robot. If Will was the show's hero, and Smith its plot-driving irritant, the Robot was its soul. See also "The Ghost Planet", "The Wreck of the Robot", "Trip Through the Robot", "The Mechanical Men", "Flight into the Future", "Deadliest of the Species", "Junkyard in Space".

BEST GUEST STAR

The Challenge — A lot to choose from — among those I haven't mentioned, Warren Oates, Werner Klemperer, Kym Karath, Strother Martin, Wally Cox, Francine York, John Carradine, Daniel J. Travanty, Lyle Waggoner, Edy Williams, Arte Johnson — but I'm going with Kurt Russell who plays a young prince from a warrior planet trying to prove to his father (Michael Ansara) that he's worthy of his trust, respect and love. A good story about father-son relationships, plus Guy Williams gets to show off the fencing skills that earned him the title role as Disney's Zorro.

BEST ALIENS

Invaders from the Fifth Dimension — The cyclops ("There Were Giants in the Earth") is the most iconic, the "bubble creatures" ("The Derelict") the most outré, but I'm going with the mouthless, disembodied heads from this one. Stranded while visiting from another dimension, they need a brain to replace a burned-out computer component and notice Will has a pretty good head on his shoulders. So they task Dr. Smith with bringing it to them on a metaphorical plate. The show would recycle this plotline over and over but the first time out of the box, it feels fresh. Plus their spaceship is cooler than anything Star Trek ever served up.

BEST OF THE REST

The Keeper, Parts One and Two — The only two-parter during the show's run, this one stars Michael Rennie (The Day the Earth Stood Still) as an intergalactic zookeeper looking for two new specimens for his exhibit — Will and Penny! Coming at the midpoint of season one, this was the high watermark of the show's original (serious) concept of a family struggling to survive in a hostile environment. After this, the camp crept in with mixed results.

Hope you watch at least one episode of Lost in Space. If you do, leave a comment and let me know what you think.

Or at least it's the one I'm writing about.

I didn't see the premiere — my devotion to the show began during its first years of syndication, about five years later — but still, pretty exciting.

And at last, all 84 episodes of Lost in Space are available on Blu-Ray, fully-restored and remastered with documentaries, interviews, a cast read-through of Bill Mumy's reunion script, and much, much more. Heee wackity do!

I assume most of you pre-ordered your set and are ripping the cellophane off the packaging even as you're reading this, planning to watch the entire series in single three-day marathon sitting. And who can blame you? But for the rest of you, maybe you don't know the series that well or — is it possible? — have never seen it at all, and would prefer to dip your toe into the shallow end of the pool, watching a few select episodes for free (with limited commercial interruption) on Hulu.

Whatever your plans, here's a list that might help you decide where to start (click on the title to watch the episode):

THE ORIGIN STORY "MINISERIES"

Not really a miniseries, of course, but interconnected chapters of one storyline, these five episodes take us from the initial liftoff through the family's first few months on an uncharted planet. Along the way, you'll discover how the Robinsons got lost in the first place, how they reacted to their first close encounter with an alien species, and how the show's best known characters, the villainous Dr. Smith and his odd-couple sidekick, the Robot, came to be on board. Featuring all the best set pieces from the unaired pilot, if you're new to the series or just looking to skim the cream off the top, this is a good place to start.

The Reluctant Stowaway

The Derelict

Island in the Sky

There Were Giants in the Earth

The Hungry Sea

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

My Friend, Mr. Nobody — A rare episode that centers on Penny (Angela Cartwright), this is a poignant fairy tale about a lonely little girl and her not-so-imaginary imaginary friend. The sort of thing Rod Serling and The Twilight Zone excelled at.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

Wish Upon a Star — Filled with the first season's signature elements, this is a top-notch morality tale about the dangers of getting everything you want, featuring wonderfully weird expressionistic cinematography, unexplained alien artifacts, the harsh reality of frontier living and Dr. Smith's self-absorbed jack-ass-ery.

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON ONE

The Space Croppers — A family of shiftless space hillbillies (led by Oscar-winner Mercedes McCambridge) cultivate a carnivorous crop that threatens to devour the Robinsons. This was the series' first full-blown foray into WTF. It wouldn't be the last.

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

The Prisoners of Space — In this, the best episode of the worst season, a menagerie of alien creatures put the Robinsons on trial for violating the laws of outer space. Kafka with monsters.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

Revolt of the Androids — A couple of androids drop in on the Robinsons, Dr. Smith hatches a get-rich-quick scheme, and human sentimentality wins the day. This one did at least spawn the catchphrase "Crush! Kill! Destroy!"

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON TWO

The Questing Beast — So many to choose from, among them "The Space Vikings", "Mutiny in Space", "Curse of Cousin Smith", etc. Here, Penny befriends a papier-mâché dragon that is being hunted by a bumbling knight in King Arthur's armor. How can something so campy be so boring?

BEST EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

The Anti-Matter Man — An experiment gone wrong transports Professor Robinson into a parallel dimension where he meets his own evil self. The scenery is summer stock by way of Dr. Caligari, and Guy Williams, having the most fun as an actor since Zorro, gets to chew on all of it. Great stuff, and for those philistines among you who won't touch black-and-white, the best of the color episodes.

MOST TYPICAL EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

Visit to a Hostile Planet — Season three was wildly uneven, but at least it was trying, leavening genuine science fiction with campy comedy. Here, the Robinsons finally make it back to Earth only to discover it's 1947 and everyone thinks they're hostile, alien invaders. A cross between Star Trek and Dad's Army. Good stuff.

WORST EPISODE OF SEASON THREE

The Great Vegetable Rebellion — Featuring a giant talking carrot played by Stanley Adams (Cyrano Jones of Star Trek's "The Trouble with Tribbles"), this is, in the words of Bill Mumy, "probably the worst television show in primetime ever made." So bad, it's good, this is gloriously awful must-see tv.

BEST GUY WILLIAMS (PROF. ROBINSON) EPISODE

Follow the Leader — The spirit of a dead alien warrior possesses Professor Robinson and turns this warm, rational man into a vicious, unpredictable bastard. Dark, moody, occasionally terrifying, pop-culture critic John Kenneth Muir called this episode a parable of "alcoholism in the nuclear family." One of the series' very best.

BEST JUNE LOCKHART (MAUREEN) EPISODE

One of Our Dogs Is Missing — Although set in 1997, the show usually ignored the fact that Betty Friedan was already a household name by 1965, but here June Lockhart gets to show her chops when Maureen is left in charge of the ship while the men are away. Threats abound and she handles them all with brains, bravery and quiet resolve.

BEST MARK GODDARD (MAJOR WEST) EPISODE

Condemned of Space — I've already mentioned "The Hungry Sea" and "The Anti-Matter Man", so I'll go with this one where the Robinsons are captured by a prison spaceship and Major West winds up hanging by his thumbs on an electronic rack. Admittedly, he had more lines in "The Space Primevals" and "Fugitives in Space", but both of those episodes suck. With Marcel Hillaire as a charming murderer who strangles his victims with a string of pearls.

BEST MARTA KRISTEN (JUDY) EPISODE

Attack of the Monster Plants — As daughter Judy, Marta Kristen rarely got a chance to shine but here she showed off a saucy bite as her own evil doppelgänger. Like much of season one, there's a dream-like quality to the mood and cinematography that papers over some of the episode's nuttier flights of fancy.

BEST BILL MUMY (WILL) EPISODE

A Change of Space — As the series' true hero, there are a lot of Will-centered episodes to choose from — "Return from Outer Space", "The Challenge", "Space Creature", among others — but I'll go with this one in which Will takes a ride in an alien space ship and winds up with the most brilliant mind in the galaxy. And still his father doesn't take him seriously! This is one of those episodes that underscores my contention that not all of the trouble Will found himself in was of Dr. Smith's making.

BEST ANGELA CARTWRIGHT (PENNY) EPISODE

The Magic Mirror — Well, the second best, and like the previously-mentioned "My Friend, Mr. Nobody", this is a poignant fairy tale about coming of age on the final frontier. Here, Penny falls through a magic mirror into a dimension with a population of one — a boy (Michael J. Pollard) who promises she'll never have to grow up. Beautiful and bittersweet.

BEST JONATHAN HARRIS (DR. SMITH) EPISODE

Time Merchant — Let's be honest, from best to worst, they were all Dr. Smith episodes. Originally, I planned to pick the episode where Smith isn't a colossal dick, but it turns out there isn't one, so instead I went with this one, an inventive and visually-Daliesque time travel story that poses the question, "What if Smith hadn't been on the show in the first place?"

BEST ROBOT EPISODE

War of the Robots — The first episode where the Robot crosses over from a mere machine, no matter how clever, into a fully-conscious Turing-Test artificial intelligence. Featuring Forbidden Planet's Robby the Robot. If Will was the show's hero, and Smith its plot-driving irritant, the Robot was its soul. See also "The Ghost Planet", "The Wreck of the Robot", "Trip Through the Robot", "The Mechanical Men", "Flight into the Future", "Deadliest of the Species", "Junkyard in Space".

BEST GUEST STAR

The Challenge — A lot to choose from — among those I haven't mentioned, Warren Oates, Werner Klemperer, Kym Karath, Strother Martin, Wally Cox, Francine York, John Carradine, Daniel J. Travanty, Lyle Waggoner, Edy Williams, Arte Johnson — but I'm going with Kurt Russell who plays a young prince from a warrior planet trying to prove to his father (Michael Ansara) that he's worthy of his trust, respect and love. A good story about father-son relationships, plus Guy Williams gets to show off the fencing skills that earned him the title role as Disney's Zorro.

BEST ALIENS

Invaders from the Fifth Dimension — The cyclops ("There Were Giants in the Earth") is the most iconic, the "bubble creatures" ("The Derelict") the most outré, but I'm going with the mouthless, disembodied heads from this one. Stranded while visiting from another dimension, they need a brain to replace a burned-out computer component and notice Will has a pretty good head on his shoulders. So they task Dr. Smith with bringing it to them on a metaphorical plate. The show would recycle this plotline over and over but the first time out of the box, it feels fresh. Plus their spaceship is cooler than anything Star Trek ever served up.

BEST OF THE REST

The Keeper, Parts One and Two — The only two-parter during the show's run, this one stars Michael Rennie (The Day the Earth Stood Still) as an intergalactic zookeeper looking for two new specimens for his exhibit — Will and Penny! Coming at the midpoint of season one, this was the high watermark of the show's original (serious) concept of a family struggling to survive in a hostile environment. After this, the camp crept in with mixed results.

Hope you watch at least one episode of Lost in Space. If you do, leave a comment and let me know what you think.

Labels:

1965,

Angela Cartwright,

Bill Mumy,

Guy Williams,

Jonathan Harris,

June Lockhart,

Kurt Russell,

Lost in Space,

Mark Goddard,

Marta Kristen,

Michael Rennie,

Review,

Science Fiction,

Television

Monday, September 14, 2015

TV's Lost in Space, Part 3: An Appreciation Beyond Nostalgia

Tomorrow is the fiftieth anniversary of the network premiere of Lost in Space. To celebrate, I'm posting a series of essays including this one which is brand spanking new.

When, lo these many months ago, I first began this series of essays about Lost in Space, it was mostly from nostalgia, revisiting a show that I loved as a kid. And I've enjoyed the effort.

But in the long run, pure nostalgia has little purchase on my brain, else I'd be raving now about Nanny and the Professor. The question is whether Lost in Space holds up now, viewed with adult eyes — and more to the point, your eyes.

It depends, of course.

If your measuring stick is so-called serious science fiction, Star Trek, say, you're almost certain to be disappointed. Although the two are often yoked together — they both aired in the mid-1960s — Star Trek and Lost in Space were in fact conceived as very different shows, mining wholly separate veins to tell different kinds of stories.

At its best, Lost in Space was a fairy tale filled with monsters, magical devices and moral lessons wrapped up in a vaguely science fiction setting. Other times, it was a slapstick comedy featuring a transgressive psychopath and a wisecracking, passive-aggressive robot — Red Dwarf by way of Pee-Wee's Playhouse. And the rest of the time, it was a traditional television Western with gunfights, frontier hardships and passing troublemakers (riding rockets instead of horses) in an outer space situated somewhere between Dodge City and the Big Dipper.

And there's nothing wrong with that.

Rod Serling, who defined science fiction as "the improbable made possible" and fantasy as "the impossible made probable," made a fortune writing in both genres. The point is to tell a good story and if in the process you can peel back the bark of polite society to reveal the human truth underneath, then you've really got something. Fairy tales endure because they allow us to confront our darkest fears — death, failure, loneliness — at a comfortable, magical remove.

For example, "My Friend, Mr. Nobody", about Penny's not-so-imaginary imaginary friend, is at its heart a poignant story of childhood loneliness and the struggle for purpose and relevance. "Wish Upon a Star" uses an unexplained alien artifact that grants every wish to explore the impact of greed on a group's sense of community and individual responsibility. And "Follow the Leader", a story ostensibly about Professor Robinson's possession by a hostile alien spirit, becomes a somber, frightening parable of "alcoholism in the nuclear family."

These stories, along with many others, used elements commonly associated with fantasy to say something true about basic human experiences such as family, community, courage, survival, sexism, and even death.

Admittedly, Lost in Space wasn't, shall we say, well-grounded in scientific accuracy. It was the sort of show that thought a radio telescope is a telescope with a radio on it. Nor did anyone seem to consider whether building an interstellar ship to transport but a single family made much sense. Generally, we prefer to clothe out scientific impossibilities — warp drives, light sabers, dinosaur clones, liquid metal terminators — in the garb of plausible mumbo jumbo.

But scientific plausibility, I contend, is beside the point. I mean, have you gone back and watched an episode of The Twilight Zone recently?

A greater stumbling block for many is Dr. Smith, the most famous — infamous — character on this or any other show. He was lazy, whiny, selfish, conniving, an all-around irritant. But might I suggest that instead of running away from Smith, you should embrace him as television's first true anti-hero.

Think about it. Long before The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Dexter or any of the other truly bad men of television's new Golden Age, indeed, at a time when Hollywood was only just beginning to shed the strictures of the Production Code, a major network built a show — a family show, mind you — around a villain who week-in and week-out plotted to murder, kidnap, betray, ransom and otherwise sell out the series' ostensible heroes. And he never received his comeuppance. There was no precedent for him.

Groundbreaking.

"Of all the many myriad characters that I have played in my life," Jonathan Harris said later, "he surely is my favorite. I like to feel that I would never in a million years have done what he did," but then added with a twinkle, "Maybe. You never know."

Still, context is everything and as you watch Smith do his nefarious thing every week, you have to ask yourself why the other characters put up with him.

The Robot's relationship with Dr. Smith, I think we instinctively get. They're Abbott and Costello, a wisecracking odd couple who fundamentally loathe each other but can't function apart. "He was my alter ego," Harris said, "and he was wise to me and a danger to me. Always calling him those dreadful alliteratives to keep him down so he wouldn't expose me."

Will's relationship with Smith is a bit harder to explain. While no responsible parent would allow a ten year old to run around with a middle-aged man of such dubious moral character, I certainly don't agree with those weisenheimers who've joked that Smith was an intergalactic pedophile. Nor do I wholly agree with Bill Mumy's assessment of Will as "young enough to be naive and manipulated." Nobody's that gullible, especially not a kid as bright as Will Robinson.

No, personally, I think that while Will was smart, honest, brave and resourceful — "smarter than the adults," Mumy said — he was also recklessly adventurous, and far from being Smith's pliable dupe, he (perhaps unwittingly) sought Smith out as a scapegoat for all the trouble he'd be getting into anyway.

"[He] knows he's got the answer that they don't," Mumy said, "and is he going to sneak out and save their butts or is he going to stay in like dad says and let everybody get messed up?"

That's why we put up with this odd relationship — we know that Will wants it's that way.

Less explicable is why the rest of the Robinsons put up with Smith. Fool me once, shame on you; fool me once a week for three straight years and that's just pathological. Maybe their willingness to overlook his repeated attempts to screw them over was meant as a sly commentary on society's tendency to pay lip service to simple virtues while rewarding psychopathic behavior.

How better to explain Donald Trump?

"Lost in Space's vision of a totally ill-prepared family blasting into space with a demented egomaniac along for the ride," wrote Hugo-award-winning author Charlie Jane Anders, "is intrinsically subversive, when compared to more militaristic (or professionalized) views of space exploration. Basically, Lost in Space is the apotheosis of camp — and it's a gloriously weird vision of our future among the stars."

Indeed, in 1968, the American Council for Better Broadcasts complained "the show is marked by violence, greed, selfishness, trickery and a disregard for accepted values!"

No wonder I like it so much.

But will you like it? Ultimately, your willingness to embrace — or at least tolerate — the campy aspects of what television historian James Van Hise called "TV's first science fiction sitcom" will determine whether you'll enjoy more than a handful of episodes.

Camp is deceptively easy to write and almost impossible to pull off. It's based on a broadly winking compact between the performer and the audience that not only does nothing on the screen really matter but also that we're fools for ever thinking it did. Done well, camp can deconstruct a genre to reveal the eternal human truths underneath and make us laugh in self-recognition. But done poorly, as unfortunately it most often is, the result is an undercooked dish of lazy contempt that's hard to swallow.

The byplay between Smith and the Robot was often brilliant and when served up as a counterpoint to the more serious scenes — check out the aforementioned "Follow the Leader" or the third season episode "The Anti-Matter Man" to see what I mean — the comedy could punch up what might otherwise play as earnest, stodgy or worse, ludicrous. But as much as the writers tried, you couldn't build entire episodes around it, any more than you can build a song on nothing but a drum solo.

The problem was not that the series got campy, the problem is that the writers got lazy — I mean, seriously, an episode starring a talking carrot? Come on! — and Irwin Allen, who was at heart a kid with a sweet tooth for schlock, let them get away with it.

Still, it made for decent ratings — finishing in the top 35 in each of its three seasons (Star Trek never finished better than 52nd) — and fifty years later, the brilliant episodes are still brilliant, and the not-so-brilliant ones, well, Smith and the Robot at the very least make me laugh. That's more than good enough for me.

Somewhere between the start of this series back in March and part 3 here, I stopped seeing Lost in Space with the nostalgic eye of a boy and found myself appreciating it with the discerning eye of a grown man. Nostalgia is a double-edged sword, giving value to old ties and traditions, but robbing you of the pleasure of the moment you're living in (Christmas, anyone?). I'll miss the Lost in Space that played for so long in my less-than-perfect memory, but I welcome the pleasure I've felt at discovering something new, something that I missed the first time around.

Lost in Space isn't quite the series I remembered. But I've grown to love it again, in some ways more than I did before. Maybe, given a chance, you'll grow to love it, too.

Tomorrow: Part 4, What To Watch.

When, lo these many months ago, I first began this series of essays about Lost in Space, it was mostly from nostalgia, revisiting a show that I loved as a kid. And I've enjoyed the effort.

But in the long run, pure nostalgia has little purchase on my brain, else I'd be raving now about Nanny and the Professor. The question is whether Lost in Space holds up now, viewed with adult eyes — and more to the point, your eyes.

It depends, of course.

If your measuring stick is so-called serious science fiction, Star Trek, say, you're almost certain to be disappointed. Although the two are often yoked together — they both aired in the mid-1960s — Star Trek and Lost in Space were in fact conceived as very different shows, mining wholly separate veins to tell different kinds of stories.

At its best, Lost in Space was a fairy tale filled with monsters, magical devices and moral lessons wrapped up in a vaguely science fiction setting. Other times, it was a slapstick comedy featuring a transgressive psychopath and a wisecracking, passive-aggressive robot — Red Dwarf by way of Pee-Wee's Playhouse. And the rest of the time, it was a traditional television Western with gunfights, frontier hardships and passing troublemakers (riding rockets instead of horses) in an outer space situated somewhere between Dodge City and the Big Dipper.

And there's nothing wrong with that.

Rod Serling, who defined science fiction as "the improbable made possible" and fantasy as "the impossible made probable," made a fortune writing in both genres. The point is to tell a good story and if in the process you can peel back the bark of polite society to reveal the human truth underneath, then you've really got something. Fairy tales endure because they allow us to confront our darkest fears — death, failure, loneliness — at a comfortable, magical remove.

For example, "My Friend, Mr. Nobody", about Penny's not-so-imaginary imaginary friend, is at its heart a poignant story of childhood loneliness and the struggle for purpose and relevance. "Wish Upon a Star" uses an unexplained alien artifact that grants every wish to explore the impact of greed on a group's sense of community and individual responsibility. And "Follow the Leader", a story ostensibly about Professor Robinson's possession by a hostile alien spirit, becomes a somber, frightening parable of "alcoholism in the nuclear family."

These stories, along with many others, used elements commonly associated with fantasy to say something true about basic human experiences such as family, community, courage, survival, sexism, and even death.

Admittedly, Lost in Space wasn't, shall we say, well-grounded in scientific accuracy. It was the sort of show that thought a radio telescope is a telescope with a radio on it. Nor did anyone seem to consider whether building an interstellar ship to transport but a single family made much sense. Generally, we prefer to clothe out scientific impossibilities — warp drives, light sabers, dinosaur clones, liquid metal terminators — in the garb of plausible mumbo jumbo.

But scientific plausibility, I contend, is beside the point. I mean, have you gone back and watched an episode of The Twilight Zone recently?

A greater stumbling block for many is Dr. Smith, the most famous — infamous — character on this or any other show. He was lazy, whiny, selfish, conniving, an all-around irritant. But might I suggest that instead of running away from Smith, you should embrace him as television's first true anti-hero.

Think about it. Long before The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Dexter or any of the other truly bad men of television's new Golden Age, indeed, at a time when Hollywood was only just beginning to shed the strictures of the Production Code, a major network built a show — a family show, mind you — around a villain who week-in and week-out plotted to murder, kidnap, betray, ransom and otherwise sell out the series' ostensible heroes. And he never received his comeuppance. There was no precedent for him.

Groundbreaking.

"Of all the many myriad characters that I have played in my life," Jonathan Harris said later, "he surely is my favorite. I like to feel that I would never in a million years have done what he did," but then added with a twinkle, "Maybe. You never know."

Still, context is everything and as you watch Smith do his nefarious thing every week, you have to ask yourself why the other characters put up with him.

The Robot's relationship with Dr. Smith, I think we instinctively get. They're Abbott and Costello, a wisecracking odd couple who fundamentally loathe each other but can't function apart. "He was my alter ego," Harris said, "and he was wise to me and a danger to me. Always calling him those dreadful alliteratives to keep him down so he wouldn't expose me."

Will's relationship with Smith is a bit harder to explain. While no responsible parent would allow a ten year old to run around with a middle-aged man of such dubious moral character, I certainly don't agree with those weisenheimers who've joked that Smith was an intergalactic pedophile. Nor do I wholly agree with Bill Mumy's assessment of Will as "young enough to be naive and manipulated." Nobody's that gullible, especially not a kid as bright as Will Robinson.

No, personally, I think that while Will was smart, honest, brave and resourceful — "smarter than the adults," Mumy said — he was also recklessly adventurous, and far from being Smith's pliable dupe, he (perhaps unwittingly) sought Smith out as a scapegoat for all the trouble he'd be getting into anyway.

"[He] knows he's got the answer that they don't," Mumy said, "and is he going to sneak out and save their butts or is he going to stay in like dad says and let everybody get messed up?"

That's why we put up with this odd relationship — we know that Will wants it's that way.

Less explicable is why the rest of the Robinsons put up with Smith. Fool me once, shame on you; fool me once a week for three straight years and that's just pathological. Maybe their willingness to overlook his repeated attempts to screw them over was meant as a sly commentary on society's tendency to pay lip service to simple virtues while rewarding psychopathic behavior.

How better to explain Donald Trump?

"Lost in Space's vision of a totally ill-prepared family blasting into space with a demented egomaniac along for the ride," wrote Hugo-award-winning author Charlie Jane Anders, "is intrinsically subversive, when compared to more militaristic (or professionalized) views of space exploration. Basically, Lost in Space is the apotheosis of camp — and it's a gloriously weird vision of our future among the stars."

Indeed, in 1968, the American Council for Better Broadcasts complained "the show is marked by violence, greed, selfishness, trickery and a disregard for accepted values!"

No wonder I like it so much.

But will you like it? Ultimately, your willingness to embrace — or at least tolerate — the campy aspects of what television historian James Van Hise called "TV's first science fiction sitcom" will determine whether you'll enjoy more than a handful of episodes.

Camp is deceptively easy to write and almost impossible to pull off. It's based on a broadly winking compact between the performer and the audience that not only does nothing on the screen really matter but also that we're fools for ever thinking it did. Done well, camp can deconstruct a genre to reveal the eternal human truths underneath and make us laugh in self-recognition. But done poorly, as unfortunately it most often is, the result is an undercooked dish of lazy contempt that's hard to swallow.

The byplay between Smith and the Robot was often brilliant and when served up as a counterpoint to the more serious scenes — check out the aforementioned "Follow the Leader" or the third season episode "The Anti-Matter Man" to see what I mean — the comedy could punch up what might otherwise play as earnest, stodgy or worse, ludicrous. But as much as the writers tried, you couldn't build entire episodes around it, any more than you can build a song on nothing but a drum solo.

The problem was not that the series got campy, the problem is that the writers got lazy — I mean, seriously, an episode starring a talking carrot? Come on! — and Irwin Allen, who was at heart a kid with a sweet tooth for schlock, let them get away with it.

Still, it made for decent ratings — finishing in the top 35 in each of its three seasons (Star Trek never finished better than 52nd) — and fifty years later, the brilliant episodes are still brilliant, and the not-so-brilliant ones, well, Smith and the Robot at the very least make me laugh. That's more than good enough for me.

Somewhere between the start of this series back in March and part 3 here, I stopped seeing Lost in Space with the nostalgic eye of a boy and found myself appreciating it with the discerning eye of a grown man. Nostalgia is a double-edged sword, giving value to old ties and traditions, but robbing you of the pleasure of the moment you're living in (Christmas, anyone?). I'll miss the Lost in Space that played for so long in my less-than-perfect memory, but I welcome the pleasure I've felt at discovering something new, something that I missed the first time around.

Lost in Space isn't quite the series I remembered. But I've grown to love it again, in some ways more than I did before. Maybe, given a chance, you'll grow to love it, too.

Tomorrow: Part 4, What To Watch.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)