A trio of bloggers are hosting this week's What a Character Blogathon: Outspoken & Freckled, Paula's Cinema Club, and Once Upon a Screen. The least I can do is offer up a trio of posts in their honor.

Today is a list of my favorite character actors from the silent era, tomorrow a similar list of silent era actresses, and on the blogathon's final day, silent supporting players who were better in the sound era.

For today's list, I've bypassed actors such as Sessue Hayakawa, William Powell and Wallace Beery who did a lot of supporting work but were also lead actors in their own right, and stuck strictly with the supporting players. (Powell and Beery will show up Monday.)

13. Snub Pollard—beginning his film career as one of the Keystone Kops, he made his name as a supporting player in the Hal Roach stable, playing the little guy with a droopy moustache in the early Harold Lloyd comedies, then later in Laurel and Hardy's silent shorts. In the sound era, he wound up playing Tex Ritter's sidekick Pee Wee in a series of Westerns.

12. Jackie Coogan—he really only served up one great performance in his career, but what a performance, as the foundling child in Charlie Chaplin's first feature film, The Kid. Grew up to play Uncle Fester on television's The Addams Family.

11. Marcel Lévesque—the rubber-faced comic relief in two of Louis Feuillade's greatest serials, Les Vampire and Judex. A great ham.

10. Rudolf Klein-Rogge—best known for his supporting work as the Inventor in Fritz Lang's dystopian sci-fi classic Metropolis, he was Lang's go-to bad guy, starring in the Mabuse films.

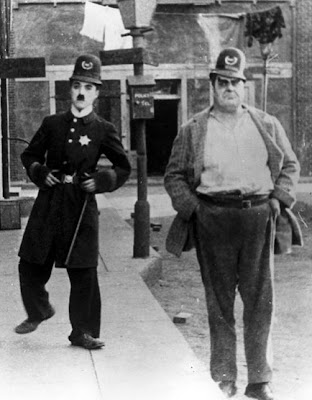

9.Eric Campbell—Chaplin's comic foil in eleven of the twelve Mutual films, including the two best shorts of Chaplin's career, Easy Street and The Immigrant. At 6' 5" and 300 pounds, he loomed over the diminutive Chaplin, giving the Tramp something solid to fight against. He died in an automobile accident in 1917.

8.Ernest Torrence—he played everything from St. Peter (The King of Kings) to Buster Keaton's father (Steamboat Bill, Jr.), and appeared in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Clara Bow's Mantrap and John Gilbert's last silent film, Desert Nights.

7. Jean Hersholt—known for his pivotal role in Erich von Stroheim's Greed, he also excelled in the Ernst Lubitsch comedy, The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, and later during the sound era as the grandfather in Shirley Temple's Heidi.

6.Donald Crisp—he won an Oscar for How Green Was My Valley, but to me, his best work was during the silent era, as Lillian Gish's viciously cruel father in Broken Blossoms and as Douglas Fairbanks's swashbuckling ally in The Black Pirate.

5.Sam De Grasse—best known for his work in the films of Douglas Fairbanks, he typically played a heavy, but with refreshing restraint and subtlety.

4. Al St. John—probably the best comic actor of the silent era who was never really a star in his own right, he worked with Roscoe Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Mabel Normand, then during the sound era as the codger sidekick in B-Westerns starring the likes of Buster Crabbe, Lash La Rue and some guy named John Wayne.

3. Conrad Veidt—you know him as Major Strasser in Casablanca, but Veidt was at his best during the silent era, starting small with such classics as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Waxworks, eventually starring in The Man Who Laughs, a film that inspired the character of the Joker in the Batman comics.

2. Theodore Roberts—a twinkly-eyed ham who made sinning look like so much fun in Cecil B. DeMille's sex comedies, yet he was equally convincing as the heavy in Joan the Woman and as Moses in The Ten Commandments. A stage actor who made his debut in 1880, he made 23 films with DeMille and appeared in 103 altogether.

1. Gustav von Seyffertitz—possibly the only actor to ever upstage the legendary Mary Pickford, his performance as the evil "baby farmer" in Sparrows ranks as one of the great fiends of the silent era. Mostly playing slippery, sly villains, he worked with everybody—DeMille, Barrymore, Garbo, Fairbanks, Valentino, Dietrich, von Sternberg, Marion Davies, Wallace Reid and, of course, Pickford—carving out a long career as the man you love to hate.

Tomorrow: My Favorite Character Actresses of the Silent Era.

Showing posts with label Theodore Roberts. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Theodore Roberts. Show all posts

Saturday, November 9, 2013

What A Character Blogathon, Part One: My Favorite Character Actors Of The Silent Era

Monday, August 12, 2013

Cecil B. DeMille's Birthday: If He Were Alive Today, He'd Be Very, Very Old

I've written at length about director/producer Cecil B. DeMille (here, for example), one of the best and most influential of the silent era directors.

If you know him only from his bloated Bible epics of the 1950s, you're probably wondering what all the fuss is about. But the fact is, beginning in 1918 with Old Wives For New, DeMille reeled off a series of "nervously brilliant, intimate melodramas" and "sly marital comedies" (Scott Eyman, Empire of Dreams) centering on the notion that grown ups engage in sexual relations and are glad that they do.

Ah, sophisticated sex comedies—God bless 'em. Here are three by DeMille to bring you up to speed:

Old Wives for New (1918)—In the first of his sex comedies, DeMille dispense with karma and moral judgment, and puts the fun back into sex, sin and every kind of bad behavior. People drink, lie, carouse and generally defy social mores, and not only suffer no consequences, they prosper. Murder goes unpunished, adultery is rewarded and divorce is presented as a sane and sophisticated solution to an unhappy marriage. Starring Elliott Dexter, Florence Vidor and Theodore Roberts.

Male and Female (1919)—DeMille added a young Gloria Swanson to the mix and both of their careers really took off. Basically, the cast of Downton Abbey gets shipwrecked on a desert island, with Swanson as a upper crust nitwit and Thomas Meighan as her butler. Of course, only the servants possess any useful survival skills. Upstairs is down, downstairs is up, in this sophisticated satire of the British class system. Also featuring Theodore Roberts and Bebe Daniels.

The Affairs of Anatol (1921)—Maybe the most famous of DeMille's comedies. Here, a bored husband (All-American heartthrob Wallace Reid) looks to spice up his love life with a series of what turn out to be disastrous affairs. By the time he returns to his senses, his wife (Swanson again) has embarked on an affair of her own. With Bebe Daniels (as Satan Synne!), Elliott Dexter and Theodore Roberts.

Have fun!

If you know him only from his bloated Bible epics of the 1950s, you're probably wondering what all the fuss is about. But the fact is, beginning in 1918 with Old Wives For New, DeMille reeled off a series of "nervously brilliant, intimate melodramas" and "sly marital comedies" (Scott Eyman, Empire of Dreams) centering on the notion that grown ups engage in sexual relations and are glad that they do.

Ah, sophisticated sex comedies—God bless 'em. Here are three by DeMille to bring you up to speed:

Old Wives for New (1918)—In the first of his sex comedies, DeMille dispense with karma and moral judgment, and puts the fun back into sex, sin and every kind of bad behavior. People drink, lie, carouse and generally defy social mores, and not only suffer no consequences, they prosper. Murder goes unpunished, adultery is rewarded and divorce is presented as a sane and sophisticated solution to an unhappy marriage. Starring Elliott Dexter, Florence Vidor and Theodore Roberts.

Male and Female (1919)—DeMille added a young Gloria Swanson to the mix and both of their careers really took off. Basically, the cast of Downton Abbey gets shipwrecked on a desert island, with Swanson as a upper crust nitwit and Thomas Meighan as her butler. Of course, only the servants possess any useful survival skills. Upstairs is down, downstairs is up, in this sophisticated satire of the British class system. Also featuring Theodore Roberts and Bebe Daniels.

The Affairs of Anatol (1921)—Maybe the most famous of DeMille's comedies. Here, a bored husband (All-American heartthrob Wallace Reid) looks to spice up his love life with a series of what turn out to be disastrous affairs. By the time he returns to his senses, his wife (Swanson again) has embarked on an affair of her own. With Bebe Daniels (as Satan Synne!), Elliott Dexter and Theodore Roberts.

Have fun!

Friday, July 27, 2012

The Great Recasting Blogathon (Part One): Ocean's Eleven As A Silent Movie

I confess, I've given most of this year's blogathons a miss, mostly because I'm working on a mammoth non-blog project that requires nearly all of my time and energy. But here's one that tickled my fancy and allowed me to write about silent movies at the same time.

I confess, I've given most of this year's blogathons a miss, mostly because I'm working on a mammoth non-blog project that requires nearly all of my time and energy. But here's one that tickled my fancy and allowed me to write about silent movies at the same time. It's called "The Great Recasting Blogathon" and it's hosted by In The Mood and Frankly My Dear, a couple of classic movie blogs you might want to check out on your own.

It's called "The Great Recasting Blogathon" and it's hosted by In The Mood and Frankly My Dear, a couple of classic movie blogs you might want to check out on your own.The rules are these:

1. Pick a movie that was made in between 1966 and today

2. Change the year of production

3. Choose new leads from Classic Hollywood

4. Choose a new director from Classic Hollywood

5. Explain why you think it would work

Well, I'm recasting the 2001 version of Ocean's Eleven—as a silent movie, of course. As you probably know, Ocean's Eleven was a remake of the 1960 Rat Pack film of the same name, which was itself a loose remake of the 1956 Jean-Pierre Melville caper classic, Bob le Flambeur.

Well, I'm recasting the 2001 version of Ocean's Eleven—as a silent movie, of course. As you probably know, Ocean's Eleven was a remake of the 1960 Rat Pack film of the same name, which was itself a loose remake of the 1956 Jean-Pierre Melville caper classic, Bob le Flambeur. But what isn't generally known—because I just this second made it up—is that Bob le Flambeur was itself a remake of one of the greatest silent films of all-time, the star-studded comedy Ocean's 11, starring Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford.

But what isn't generally known—because I just this second made it up—is that Bob le Flambeur was itself a remake of one of the greatest silent films of all-time, the star-studded comedy Ocean's 11, starring Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford.Don't remember that one, you say? Well, here's the story:

It was 1919, and the world's three most popular movie stars—Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin—had just joined forces with the world's most popular director—D.W. Griffith—to form a new distribution company they called "United Artists."

For years, studio middle men had charged exorbitant fees simply to send the quartet's films out to the nation's theaters, a service that required little more than a large envelope and a postage stamp. With the formation of United Artists, Fairbanks, Pickford, Chaplin and Griffith would henceforth lick their own stamps, and each entertained visions of vast sums of money rolling in as compensation for the effort.

For years, studio middle men had charged exorbitant fees simply to send the quartet's films out to the nation's theaters, a service that required little more than a large envelope and a postage stamp. With the formation of United Artists, Fairbanks, Pickford, Chaplin and Griffith would henceforth lick their own stamps, and each entertained visions of vast sums of money rolling in as compensation for the effort.There was only one problem: they had no new product to distribute.

"Hey, kids," suggested Fairbanks, "why don't we put on a show!"

A great idea, everyone agreed, but what kind of show? They hit upon the happy notion of a musical revue called The Jazz Singer until someone remembered that this was the silent era and they were going to look pretty silly belting out show tunes that no one could hear.

A great idea, everyone agreed, but what kind of show? They hit upon the happy notion of a musical revue called The Jazz Singer until someone remembered that this was the silent era and they were going to look pretty silly belting out show tunes that no one could hear. Next, Griffith proposed they do a variation on his usual storyline, which was to reduce a complex historical event to a question of who got into Lillian Gish's underpants first, à la The Birth of a Nation, Hearts of the World and Orphans of the Storm. The others were skeptical as it was, then vetoed the idea outright when they learned Gish wouldn't actually be in the movie—just her underpants.

Next, Griffith proposed they do a variation on his usual storyline, which was to reduce a complex historical event to a question of who got into Lillian Gish's underpants first, à la The Birth of a Nation, Hearts of the World and Orphans of the Storm. The others were skeptical as it was, then vetoed the idea outright when they learned Gish wouldn't actually be in the movie—just her underpants."How about an adaptation of Little Women," said Pickford. "Of course, you three will have to play your parts in drag, but if I can play a twelve year old girl, surely you can, too."

"I've never done drag comedy," Chaplin lied, blushing, "and don't call me Shirley! Besides, I've got a great idea for a movie, a scathing indictment of capitalism and the industrial age I call Modern Times."

"I've never done drag comedy," Chaplin lied, blushing, "and don't call me Shirley! Besides, I've got a great idea for a movie, a scathing indictment of capitalism and the industrial age I call Modern Times.""Sounds fabulous," said Fairbanks. "When can you start production?"

"1936."

Reluctantly admitting they had no useable ideas, Fairbanks wired his old friend, writer Anita Loos. Loos had written a number of films for Fairbanks in 1916 and 1917, including the breakthrough hits The Matrimaniac and Wild and Woolly, and he was eager to work with her again. "She's busy writing a novel called Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," he reported the next day, "but for us, she's willing to set it aside for a percentage of the profits."

Griffith laughed. "Everybody knows movies never turn a profit! Why, even Gone with the Wind and Star Wars haven't turned a profit!"

Deluded by visions of great wealth, Loos cranked out one of her typically witty, fast-paced scripts, something she called United Artists Presents a D.W. Griffith Film Starring Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford in a Story about a Team of Con-Artists who Break the Bank at the Gambling Casino in Monte Carlo so that One of Them (Fairbanks) Can Win Back his Ex-Wife (Pickford) While Making All His Pals (including Chaplin) Rich in the Process.

Deluded by visions of great wealth, Loos cranked out one of her typically witty, fast-paced scripts, something she called United Artists Presents a D.W. Griffith Film Starring Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford in a Story about a Team of Con-Artists who Break the Bank at the Gambling Casino in Monte Carlo so that One of Them (Fairbanks) Can Win Back his Ex-Wife (Pickford) While Making All His Pals (including Chaplin) Rich in the Process."The title's a bit unwieldy," Pickford said, "but otherwise, it's perfect."

"Yeah, well, to make it work you're gonna need a crew as nuts as you are!" Loos said. "So who have you got in mind?"

The top-billed talent was easy. Fairbanks would play the lead, a handsome con artist named Daniel Ocean, while Chaplin would play his sidekick, Rusty Ryan—an agreeable distribution of chores, as the former would require some vigorous stunt work while the latter entailed split-second comic timing.

The top-billed talent was easy. Fairbanks would play the lead, a handsome con artist named Daniel Ocean, while Chaplin would play his sidekick, Rusty Ryan—an agreeable distribution of chores, as the former would require some vigorous stunt work while the latter entailed split-second comic timing.Pickford would, of course, play the ex-wife, Tess.

Chaplin was especially looking forward to getting out of the Tramp costume for once. "That character has run its course," he said flatly. "A hundred years from now, who'll even remember him?"

For the plum part of the man they set out to rob, casino owner Terry Benedict, Pickford suggested Sessue Hayakawa. Hayakawa had risen to stardom on the strength of his seductively handsome yet cruelly ruthless villain in Cecil B. DeMille's The Cheat, a rare feat in the deeply racist Hollywood of the day.

For the plum part of the man they set out to rob, casino owner Terry Benedict, Pickford suggested Sessue Hayakawa. Hayakawa had risen to stardom on the strength of his seductively handsome yet cruelly ruthless villain in Cecil B. DeMille's The Cheat, a rare feat in the deeply racist Hollywood of the day."If you've seen him in The Cheat," Pickford said, "you know he's perfect—hot and snaky and deliciously evil. You don't know whether to run away or cover him in whipped cream and eat him for dessert. Yummy!"

"Wait, what's this about whipped cream?" said Fairbanks.

In addition to a satisfying villain, the film also required an all-star cast of comedians to play a rogues gallery of crooks and con men—each with a specialized skill that would require careful casting.

In addition to a satisfying villain, the film also required an all-star cast of comedians to play a rogues gallery of crooks and con men—each with a specialized skill that would require careful casting.For example, the part of "the grease man," a contortionist who opens the casino's safe from inside the vault, required not just a comedian but an acrobat of near superhuman athletic ability.

"Buster Keaton," Chaplin said immediately. "He's funnier than a locomotive, throws a pie faster than a speeding bullet, and can fall out of a building in a single bound. Not to mention his Twitter feed is a riot! He's playing second banana to Roscoe Arbuckle, but that's not going to last long. Offer him anything but top billing."

Keaton jumped at the offer when Fairbanks called. "I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time," he said. "Plus I need the money."

Keaton jumped at the offer when Fairbanks called. "I classify Chaplin as the greatest motion picture comedian of all time," he said. "Plus I need the money."For one of two brothers who drive each other (and everybody else) crazy, Chaplin recommended his former British stage partner who was currently making comedy shorts for Bronco Billy Anderson. "Splendid chap named Stan Laurel."

For the other brother, D.W. Griffith suggested a fellow Southerner, a plump Georgian under contract at Vitagraph named Oliver Hardy. "I don't believe they've worked together before," Griffith said, "but something tells me Laurel and Hardy would make a sensational comedy team."

One of the film's pivotal roles was that of a high roller who would convince Hayakawa to open the casino's safe to him. "For this role, we need an older actor," Griffith said, "a twinkly-eyed ham who can get a laugh from a death scene."

One of the film's pivotal roles was that of a high roller who would convince Hayakawa to open the casino's safe to him. "For this role, we need an older actor," Griffith said, "a twinkly-eyed ham who can get a laugh from a death scene." "Theodore Roberts!!!" everyone said simultaneously.

"Theodore Roberts!!!" everyone said simultaneously.Roberts had proven equally adept at drama and comedy during a run of highly-successful character parts in such films as Joan the Woman, Old Wives For New and The Roaring Road. Both Pickford and Fairbanks had worked with him before and would work with him again.

For another "older" part, that of a disgruntled ex-casino owner who would bankroll the caper, Chaplin suggested a colleague from his Mack Sennett days, Ford Sterling.

Audiences of the time would best remember Sterling as the first leader of the Keystone Kops. He had recently played the Kaiser in an oddball cross-dressing comedy, Yankee Doodle in Berlin, starring Bothwell Browne as an army officer who disguises himself as a woman to infiltrate enemy headquarters and enjoys the masquerade entirely too much.

Audiences of the time would best remember Sterling as the first leader of the Keystone Kops. He had recently played the Kaiser in an oddball cross-dressing comedy, Yankee Doodle in Berlin, starring Bothwell Browne as an army officer who disguises himself as a woman to infiltrate enemy headquarters and enjoys the masquerade entirely too much."It'll be nice working with proper comedians again," he said after receiving Chaplin's offer. "Just give me a pie and tell me who to throw it at and I'm good to go."

For the role of the munitions expert, Chaplin suggested the legendary French comedian, Max Linder. Linder had been the biggest star in Europe prior to the Great War, and Chaplin had modeled his style after him, but Linder's career had gone into decline after the actor was injured by mustard gas on the Western Front.

"The notion of Max handling high explosives would get a terrific laugh in the overseas market," Chaplin said, "and I would like to help him revive his career."

"The notion of Max handling high explosives would get a terrific laugh in the overseas market," Chaplin said, "and I would like to help him revive his career." To play the "inside man," an employee of the casino who could come and go without drawing attention to himself, they chose Noble Johnson, a talented character actor with an imposing physique and a gift for disguises. One of the few African-American actors working regularly in Hollywood, Johnson ran a studio of his own, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, dedicated to producing high-quality "race films" (as they were then known) such as The Realization of a Negro's Ambition. Griffith knew him from Intolerance where he had cast him as a Babylonian soldier.

To play the "inside man," an employee of the casino who could come and go without drawing attention to himself, they chose Noble Johnson, a talented character actor with an imposing physique and a gift for disguises. One of the few African-American actors working regularly in Hollywood, Johnson ran a studio of his own, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, dedicated to producing high-quality "race films" (as they were then known) such as The Realization of a Negro's Ambition. Griffith knew him from Intolerance where he had cast him as a Babylonian soldier.The part of the computer nerd who hacks the casino's security systems proved to be a head-scratcher.

"What's a nerd?" asked Pickford. "For that matter, what's a computer?"

But after further discussion revealed that what the part required was someone who was supposed to be a genius but was in fact a quirky, funny-looking goofball, they settled on Ben Turpin whose eyes had been insured for $25,000 in case of accidental uncrossing.

But after further discussion revealed that what the part required was someone who was supposed to be a genius but was in fact a quirky, funny-looking goofball, they settled on Ben Turpin whose eyes had been insured for $25,000 in case of accidental uncrossing."He was just a funny-looking guy," Buster Keaton said later. "You know what I mean? We introduced his character as 'a man's man,' and Ben Turpin entered. That was the biggest laugh of the picture."

Over a late supper in a suite in the Hollywood Hotel, Fairbanks reviewed the cast list with Pickford. "Turpin makes ten," he said. "Ten oughta do it, don't you think? You think we need one more? You think we need one more. All right, we'll get one more."

Over a late supper in a suite in the Hollywood Hotel, Fairbanks reviewed the cast list with Pickford. "Turpin makes ten," he said. "Ten oughta do it, don't you think? You think we need one more? You think we need one more. All right, we'll get one more.""What we need," Fairbanks told Chaplin at lunch the next day, repeating a suggestion of Pickford's, "is an innocent, all-American boy type—but here's the catch: one who can match me move for move in the scene where I climb down the elevator shaft. Who you got?"

"That would be Harold Lloyd," Chaplin said. "He recently invented a boy-with-glasses character that I think is going to be a big hit. And he's handsome and can climb buildings even better than you can."

"That would be Harold Lloyd," Chaplin said. "He recently invented a boy-with-glasses character that I think is going to be a big hit. And he's handsome and can climb buildings even better than you can.""Well, we'll use him anyway," Fairbanks said.

The film, now retitled Ocean's 11, began production in the summer of 1919. Griffith directed the action sequences with his usual flare, but Chaplin balked at taking comedy advice from a man who thought the sack of Babylon was a laugh riot. Although Griffith received sole directorial credit, scholars now believe Chaplin was responsible for most of the film's non-action sequences.

The film, now retitled Ocean's 11, began production in the summer of 1919. Griffith directed the action sequences with his usual flare, but Chaplin balked at taking comedy advice from a man who thought the sack of Babylon was a laugh riot. Although Griffith received sole directorial credit, scholars now believe Chaplin was responsible for most of the film's non-action sequences.While the two men would remain partners in the United Artists venture, they de-friended each other on Facebook soon after filming was complete, and for years thereafter rang each other's doorbell late at night and ran away.

Less apparent on the set, but no less problematic, was the tension between Fairbanks' 100% irony-free acting style and Chaplin's compulsion to deflate all larger-than-life figures. The scene, for example, where Ocean talks Rusty into robbing the casino—"Why not do it?"—took over 400 takes alone, with either Fairbanks boisterously breaking character or Chaplin kicking him in the pants.

Less apparent on the set, but no less problematic, was the tension between Fairbanks' 100% irony-free acting style and Chaplin's compulsion to deflate all larger-than-life figures. The scene, for example, where Ocean talks Rusty into robbing the casino—"Why not do it?"—took over 400 takes alone, with either Fairbanks boisterously breaking character or Chaplin kicking him in the pants. Still, film-industry insiders and the movie-going public alike were abuzz with anticipation of the picture's Christmas Day premiere, and the four co-founders of United Artists had high hopes for a commercial and critical success. "This is going to be bigger than The Birth of a Nation," Griffith boasted. "Funnier, too."

Still, film-industry insiders and the movie-going public alike were abuzz with anticipation of the picture's Christmas Day premiere, and the four co-founders of United Artists had high hopes for a commercial and critical success. "This is going to be bigger than The Birth of a Nation," Griffith boasted. "Funnier, too."Then tragedy struck. While awaiting shipment to theaters across the country, the highly-combustible elements in the movie's silver nitrate film stock caught fire, destroying not only the warehouse where the film was stored, but also the original negative and every print.

In a moment, Ocean's 11 joined the long list of silent films lost forever. Only a few fragments remain:

Film fans can only dream of what might have been.

"We're ruined," Fairbanks sobbed, "ruined before we ever made a movie!"

"Hardly," said Pickford. "While you were busy buckling your swash, I had the foresight to insure the film for $10 million with Lloyds of London—which is $9 million more than it cost to make! Not only are we not ruined, we're richer than ever!"

"Mary, you're wonderful!" said Fairbanks, dropping to one knee. "Will you marry me?"

"Mary, you're wonderful!" said Fairbanks, dropping to one knee. "Will you marry me?""You bet I will, you gorgeous hunk o' man, you! Come here and kiss me!"

"Rowr!"

Tomorrow: More posters from silent movies you will never see.

Monday, June 11, 2012

Old Wives For New: Sex, Sin And Cecil B. DeMille

As has been the case with nearly every technical innovation in the visual arts since the first man painted pictures on a cave wall, sex proved to be a key selling point in the marketing of the new motion picture technology to curious audiences. In 1896, just six years after Thomas Edison began his experiments with film, William Heise recorded May Irwin and John C. Rice recreating the kiss from their Broadway hit, The Widow Jones.

As has been the case with nearly every technical innovation in the visual arts since the first man painted pictures on a cave wall, sex proved to be a key selling point in the marketing of the new motion picture technology to curious audiences. In 1896, just six years after Thomas Edison began his experiments with film, William Heise recorded May Irwin and John C. Rice recreating the kiss from their Broadway hit, The Widow Jones.The resulting twenty second clip—called, appropriately enough, The Kiss—was the first such act ever recorded on film. The moralizing classes reacted with outraged spluttering; the paying public made it Edison's top grossing film of the year.

Other filmmakers quickly scrambled to sell their own take on this most important of human endeavors, as the resulting efforts serve as something of a Rorschach test for directors, writers, actors and the audiences themselves. Georges Méliès, for example, chose to titillate his audiences with suggestions of nudity. Russian, Italian, Swedish and Dutch directors offered up sex as a source of tragedy and misery. America's greatest director, D.W. Griffith, moralized, while his comic counterpart, Mack Sennett, guffawed. That Theda Bara—whose name was famously billed as an anagram of "Arab Death"—wound up representing both the allure and the danger of sex in the late 1910s tells you all you need to know about the state of the American psyche during the first world war.

Other filmmakers quickly scrambled to sell their own take on this most important of human endeavors, as the resulting efforts serve as something of a Rorschach test for directors, writers, actors and the audiences themselves. Georges Méliès, for example, chose to titillate his audiences with suggestions of nudity. Russian, Italian, Swedish and Dutch directors offered up sex as a source of tragedy and misery. America's greatest director, D.W. Griffith, moralized, while his comic counterpart, Mack Sennett, guffawed. That Theda Bara—whose name was famously billed as an anagram of "Arab Death"—wound up representing both the allure and the danger of sex in the late 1910s tells you all you need to know about the state of the American psyche during the first world war.But sex as something adults engage in without shame or embarrassment—well, not so much. We tend to assume, when think of it at all, that sophisticated sex in the cinema must have been the invention of Ernst Lubitsch. And while it's true Lubitsch was a master of the light touch when it came to the subject, he didn't really acquire that touch until 1924, with The Marriage Circle. Before that, he tended toward heavy costume dramas and broad farces.

Instead, the sophisticated sex movie was a creation from the most unlikely of sources—cinema's most famous purveyor of Bible epics and historical dramas, Cecil Blount DeMille.

Instead, the sophisticated sex movie was a creation from the most unlikely of sources—cinema's most famous purveyor of Bible epics and historical dramas, Cecil Blount DeMille.Some of my readers—those reared on The Ten Commandments and The Greatest Show On Earth—might guffaw to read his name in the same sentence with "sophisticated" and "sex," but the fact is, beginning in 1918 with Old Wives For New, DeMille reeled off a series of "nervously brilliant, intimate melodramas" and "sly marital comedies" (Scott Eyman, Empire of Dreams) centering on the notion that grown ups engage in sexual relations and are glad that they do.

The son of a playwright and an acting teacher, DeMille began acting in New York at the age of nineteen and in little more than a decade became a successful Broadway director and producer. He also wrote several one-act operettas for producer Jesse L. Lasky and it was this association that led him into motion pictures. Lasky aspired to combine what he saw as the "high art" of theater with the money-making potential of mass-produced movies, and with the reluctant financial backing of his brother-in-law, Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn), Lasky teamed up with DeMille to found the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Film Company.

It was a grandiose gesture considering that neither man had ever made so much as a one-reel short before, but the two set off for the western United States to film a feature-length version of The Squaw Man, a popular stage play of the era. The two stopped first in Flagstaff, Arizona, but DeMille pictured wide open spaces rather than mountains for the wild west storyline, so they continued west until they settled in a sleepy village north of Los Angeles called "Hollywood."

It was a grandiose gesture considering that neither man had ever made so much as a one-reel short before, but the two set off for the western United States to film a feature-length version of The Squaw Man, a popular stage play of the era. The two stopped first in Flagstaff, Arizona, but DeMille pictured wide open spaces rather than mountains for the wild west storyline, so they continued west until they settled in a sleepy village north of Los Angeles called "Hollywood."Legend has it that they set up shop in a barn, but legend neglects to mention that L.L. Burns and Harry Reiver, a couple of established filmmakers with American Gaumont, had converted the barn into a studio nine months earlier. No matter. The Squaw Man was the first feature film ever made in Hollywood, and when it grossed $244,000 on an investment of $15,000, DeMille's future was assured.

Although DeMille's education as a film director consisted of a day spent at the Edison studios to see how the cameras worked, and watching Oscar Apfel "co"-direct The Squaw Man, he quickly demonstrated a grasp of the film medium superior to all but a few of his peers. In his biography Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood, Robert S. Birchard notes that within a half-dozen movies of his first one, DeMille had moved the camera closer to his actors, "showing a greater reliance on personality and subtlety of performance," had picked up the pace of both individual scenes and his films as a whole, and, by using light and shadow in a groundbreaking way to accent (or obscure) aspects of the production, "set a much-imitated standard for visual excellence."

Although DeMille's education as a film director consisted of a day spent at the Edison studios to see how the cameras worked, and watching Oscar Apfel "co"-direct The Squaw Man, he quickly demonstrated a grasp of the film medium superior to all but a few of his peers. In his biography Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood, Robert S. Birchard notes that within a half-dozen movies of his first one, DeMille had moved the camera closer to his actors, "showing a greater reliance on personality and subtlety of performance," had picked up the pace of both individual scenes and his films as a whole, and, by using light and shadow in a groundbreaking way to accent (or obscure) aspects of the production, "set a much-imitated standard for visual excellence."I

n all, DeMille directed thirty-seven movies between 1914 and early 1918, dipping into a variety of genres including Westerns, costume dramas and even a pair of Mary Pickford movies. The best of these early films was The Cheat, made in 1915 and featuring Sessue Hayakawa in a star-making role as an unscrupulous businessman who barters money for sex from a spoiled housewife and then brands her with an iron when she reneges on the deal.

n all, DeMille directed thirty-seven movies between 1914 and early 1918, dipping into a variety of genres including Westerns, costume dramas and even a pair of Mary Pickford movies. The best of these early films was The Cheat, made in 1915 and featuring Sessue Hayakawa in a star-making role as an unscrupulous businessman who barters money for sex from a spoiled housewife and then brands her with an iron when she reneges on the deal.As Simon Louvish notes in his biography Cecil B. DeMille: A Life in Art, The Cheat "electrified audiences, who were not accustomed to this degree of emotion in a tale dealing with rampant sexual desire ...."

These early films demonstrated DeMille's interest in melodrama, spectacle and lurid romance, which perhaps explains his interest in the subject of his thirty-eighth film, a popular novel called Old Wives For New (available free online here). Business partner Jesse Lasky pushed this story of a marriage that disintegrates in boredom, adultery and divorce to get DeMille "away from the spectacle stuff for one or two pictures and try to do modern stories of great human interest."

These early films demonstrated DeMille's interest in melodrama, spectacle and lurid romance, which perhaps explains his interest in the subject of his thirty-eighth film, a popular novel called Old Wives For New (available free online here). Business partner Jesse Lasky pushed this story of a marriage that disintegrates in boredom, adultery and divorce to get DeMille "away from the spectacle stuff for one or two pictures and try to do modern stories of great human interest."And since Lasky was the one footing the bill, DeMille chose to follow his advice. The studio bought the film rights for $6,500.

Although the novel's author, David Graham Phillips, was a pretty interesting character in his own right—a muckraking journalist who exposed the nexus between corporate money and the U.S. Senate, he was murdered by a man who believed Phillips had libeled his family—the novel itself was 495 pages of "clover" and "heaving bosoms," turning a tale that included adultery, murder, blackmail and skullduggery into something earnest and flowery and dull.

Although the novel's author, David Graham Phillips, was a pretty interesting character in his own right—a muckraking journalist who exposed the nexus between corporate money and the U.S. Senate, he was murdered by a man who believed Phillips had libeled his family—the novel itself was 495 pages of "clover" and "heaving bosoms," turning a tale that included adultery, murder, blackmail and skullduggery into something earnest and flowery and dull.To adapt the novel, DeMille turned to his favorite writer—and favorite mistress—Jeanie Macpherson. During their long sexual and professional relationship, MacPherson worked on forty screenplays for DeMille, including such silent classics as The Cheat, Joan the Woman, Male and Female, The Affairs of Anatol, The Ten Commandments and The King of Kings.

To condense the sprawling tale, Macpherson reduced an episodic narrative spread out over decades into three tight acts with a single flashback to explain how the bored husband had ever fallen for his plump, drab, dowdy wife in the first place. She also added witty intertitles that transformed the melodrama into a sharp satire of upper-class manners.

To condense the sprawling tale, Macpherson reduced an episodic narrative spread out over decades into three tight acts with a single flashback to explain how the bored husband had ever fallen for his plump, drab, dowdy wife in the first place. She also added witty intertitles that transformed the melodrama into a sharp satire of upper-class manners.As the film begins, oil baron Charles Murdock (Elliott Dexter) is on the verge of what we now call a mid-life crisis. While he's respected as a "genius" in the world of business, at home he's little more than a cipher—a human ATM machine to his kids, a nursemaid to his hypochondriac wife. He sits alone in his study, dejected, depressed, with only his dog for companionship.

Next, DeMille introduces us in shotgun fashion to the five supporting characters who will combine to remake Murdock's life—Sylvia Ashton as his not-so-pleasingly plump wife; Marcia Manon as a "painted lady;" Florence Vidor as Juliette Raeburn, a successful New York dressmaker, who, according to the intertitles, "was finally to cut the thread of his fate;" and two of the finest character actors of the silent era, Gustav von Seyffertitz as his "crafty" secretary; and Theodore Roberts as Murdock's dissolute business partner.

Next, DeMille introduces us in shotgun fashion to the five supporting characters who will combine to remake Murdock's life—Sylvia Ashton as his not-so-pleasingly plump wife; Marcia Manon as a "painted lady;" Florence Vidor as Juliette Raeburn, a successful New York dressmaker, who, according to the intertitles, "was finally to cut the thread of his fate;" and two of the finest character actors of the silent era, Gustav von Seyffertitz as his "crafty" secretary; and Theodore Roberts as Murdock's dissolute business partner.In each of these vignettes, DeMille shows a close-up of the character's hands—the wife picking through bon bons, the courtesan reaching for rouge—as if to say that a person is what he does not what he says, and no matter what he believes about himself or wants you to believe about him, his actions will always reveal his true character.

After following Murdock through his frustrating morning routine, DeMille treats us to the most cleverly edited sequence of the film, a flashback to Murdock's initial courtship of his wife that cuts back and forth between the young couple and his present-day wife bursting in on her husband's reverie, as if she's catching them in flagrante delicto—a remarkable show of faith on DeMille's part that, even though the classical Hollywood "style" had only become the industry standard the year before, his audience would understand what's going on.

After following Murdock through his frustrating morning routine, DeMille treats us to the most cleverly edited sequence of the film, a flashback to Murdock's initial courtship of his wife that cuts back and forth between the young couple and his present-day wife bursting in on her husband's reverie, as if she's catching them in flagrante delicto—a remarkable show of faith on DeMille's part that, even though the classical Hollywood "style" had only become the industry standard the year before, his audience would understand what's going on. Similarly, DeMille later uses lap dissolves and iris-shots-within-iris-shots to convey the content of Murdock's daydreams, trusting his audience to understand what he saying without spelling it out in clumsy intertitles or belabored scenes, a testament both to how quickly film had progressed in five years and how cutting edge DeMille really was. As a result, he's able to maintain a sprightly pace—and sweep past some of the story's more improbable twists.

Similarly, DeMille later uses lap dissolves and iris-shots-within-iris-shots to convey the content of Murdock's daydreams, trusting his audience to understand what he saying without spelling it out in clumsy intertitles or belabored scenes, a testament both to how quickly film had progressed in five years and how cutting edge DeMille really was. As a result, he's able to maintain a sprightly pace—and sweep past some of the story's more improbable twists.Technical innovations aside, though, it was the substance of Old Wives For New that made the film so groundbreaking.

The married Murdock meets Juliette, fools her into believing he's a much younger—and unattached—man, and falls in love with her. Attempting to drown both the memory of Juliette and the misery of his domestic situation, Murdock follows his business partner into the champagne-soaked fleshpots of New York City, an excursion that leads to murder, scandal and divorce (a sequence of events that must have reminded audiences in 1918 of Stanford White's murder during a musical revue on the roof of Madison Square Garden).

The married Murdock meets Juliette, fools her into believing he's a much younger—and unattached—man, and falls in love with her. Attempting to drown both the memory of Juliette and the misery of his domestic situation, Murdock follows his business partner into the champagne-soaked fleshpots of New York City, an excursion that leads to murder, scandal and divorce (a sequence of events that must have reminded audiences in 1918 of Stanford White's murder during a musical revue on the roof of Madison Square Garden). In turning this set-up into a happy ending, DeMille essentially made a pre-Code film before there was a Code to subvert, dispensing with karma and moral judgment, and putting the fun back into sex, sin and every kind of bad behavior. People drink, lie, carouse and generally defy social mores, and not only suffer no consequences, they prosper. Murder goes unpunished, adultery is rewarded and divorce is presented as a sane and sophisticated solution to an unhappy marriage.

In turning this set-up into a happy ending, DeMille essentially made a pre-Code film before there was a Code to subvert, dispensing with karma and moral judgment, and putting the fun back into sex, sin and every kind of bad behavior. People drink, lie, carouse and generally defy social mores, and not only suffer no consequences, they prosper. Murder goes unpunished, adultery is rewarded and divorce is presented as a sane and sophisticated solution to an unhappy marriage."In scene after scene," Birchard wrote, "Old Wives for New must have been startling for 1918 audiences." Photoplay condemned the film's "disgusting debauchery" and clucked that "Cecil B. DeMille, director, seemed to revel in the most immoral episodes."

Adolph Zukor was so shocked by the film's suggestion that divorce might be the appropriate end for some marriages that he held up its distribution, only relenting after positive reactions during audience testing.

Adolph Zukor was so shocked by the film's suggestion that divorce might be the appropriate end for some marriages that he held up its distribution, only relenting after positive reactions during audience testing. Old Wives For New premiered on May 19, 1918, and Photoplay's sputtering outrage aside, the reviews were generally positive. "There are somewhat risqué situations in the story," The Motion Picture News wrote, "but these have been handled delicately. It is not a story that children will understand, and it is one that the prudes will consider a reflection on themselves. All in all, it is one of the most satisfactory pictures that has been shown on Broadway in months."

Old Wives For New premiered on May 19, 1918, and Photoplay's sputtering outrage aside, the reviews were generally positive. "There are somewhat risqué situations in the story," The Motion Picture News wrote, "but these have been handled delicately. It is not a story that children will understand, and it is one that the prudes will consider a reflection on themselves. All in all, it is one of the most satisfactory pictures that has been shown on Broadway in months."Variety praised DeMille's direction as "expert."

Financially, the picture did well, grossing nearly $300,000 on a budget of $66,000, but its impact on the culture was even greater, ushering in an era of adult-themed movies, including not only DeMille's own risque classics Male and Female and The Affairs of Anatol (adding Gloria Swanson to the mix), but also Chaplin's A Woman of Paris, Murnau's Sunrise and pretty much Lubitsch's entire oeuvre.

"Those who find it fashionable to denigrate [DeMille]," wrote Gene Ringgold and DeWitt Boden in The Films of Cecil B. DeMille, "ignore the high regard in which his work as a director was held by critics and film historians during those first years ... Among directors, only his name and those of D.W. Griffith and Alfred Hitchcock were really sufficient in themselves to attract top box-office trade."

Maybe in the long run, DeMille's primary contribution was in figuring out how to sell sex to American audiences that were both curious and squeamish. Here, he hit it directly; later he dressed it up in historical and Biblical epics that allowed his audiences to piously condemned the sin while lingering over every salacious detail. He let the public have its cake and eat it too, and was rewarded with forty-two years of unbroken commercial success—one of the longest and most profitable careers in Hollywood history.

Maybe in the long run, DeMille's primary contribution was in figuring out how to sell sex to American audiences that were both curious and squeamish. Here, he hit it directly; later he dressed it up in historical and Biblical epics that allowed his audiences to piously condemned the sin while lingering over every salacious detail. He let the public have its cake and eat it too, and was rewarded with forty-two years of unbroken commercial success—one of the longest and most profitable careers in Hollywood history. His kind of films long ago went out of fashion, but don't kid yourself: DeMille was as instrumental during the silent era as Griffith and Chaplin in selling the habit of movie-going to American audiences, no small accomplishment.

His kind of films long ago went out of fashion, but don't kid yourself: DeMille was as instrumental during the silent era as Griffith and Chaplin in selling the habit of movie-going to American audiences, no small accomplishment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)