A trio of bloggers are hosting this week's What a Character Blogathon: Outspoken & Freckled, Paula's Cinema Club, and Once Upon a Screen. The least I can do is offer up a trio of posts in their honor.

Today is a list of my favorite character actors from the silent era, tomorrow a similar list of silent era actresses, and on the blogathon's final day, silent supporting players who were better in the sound era.

For today's list, I've bypassed actors such as Sessue Hayakawa, William Powell and Wallace Beery who did a lot of supporting work but were also lead actors in their own right, and stuck strictly with the supporting players. (Powell and Beery will show up Monday.)

13. Snub Pollard—beginning his film career as one of the Keystone Kops, he made his name as a supporting player in the Hal Roach stable, playing the little guy with a droopy moustache in the early Harold Lloyd comedies, then later in Laurel and Hardy's silent shorts. In the sound era, he wound up playing Tex Ritter's sidekick Pee Wee in a series of Westerns.

12. Jackie Coogan—he really only served up one great performance in his career, but what a performance, as the foundling child in Charlie Chaplin's first feature film, The Kid. Grew up to play Uncle Fester on television's The Addams Family.

11. Marcel Lévesque—the rubber-faced comic relief in two of Louis Feuillade's greatest serials, Les Vampire and Judex. A great ham.

10. Rudolf Klein-Rogge—best known for his supporting work as the Inventor in Fritz Lang's dystopian sci-fi classic Metropolis, he was Lang's go-to bad guy, starring in the Mabuse films.

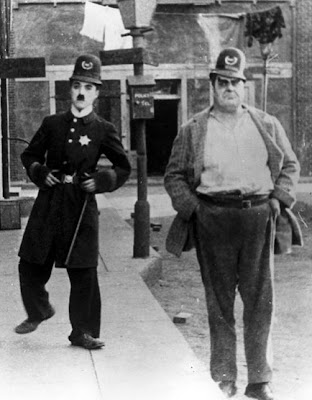

9.Eric Campbell—Chaplin's comic foil in eleven of the twelve Mutual films, including the two best shorts of Chaplin's career, Easy Street and The Immigrant. At 6' 5" and 300 pounds, he loomed over the diminutive Chaplin, giving the Tramp something solid to fight against. He died in an automobile accident in 1917.

8.Ernest Torrence—he played everything from St. Peter (The King of Kings) to Buster Keaton's father (Steamboat Bill, Jr.), and appeared in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Clara Bow's Mantrap and John Gilbert's last silent film, Desert Nights.

7. Jean Hersholt—known for his pivotal role in Erich von Stroheim's Greed, he also excelled in the Ernst Lubitsch comedy, The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, and later during the sound era as the grandfather in Shirley Temple's Heidi.

6.Donald Crisp—he won an Oscar for How Green Was My Valley, but to me, his best work was during the silent era, as Lillian Gish's viciously cruel father in Broken Blossoms and as Douglas Fairbanks's swashbuckling ally in The Black Pirate.

5.Sam De Grasse—best known for his work in the films of Douglas Fairbanks, he typically played a heavy, but with refreshing restraint and subtlety.

4. Al St. John—probably the best comic actor of the silent era who was never really a star in his own right, he worked with Roscoe Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Mabel Normand, then during the sound era as the codger sidekick in B-Westerns starring the likes of Buster Crabbe, Lash La Rue and some guy named John Wayne.

3. Conrad Veidt—you know him as Major Strasser in Casablanca, but Veidt was at his best during the silent era, starting small with such classics as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Waxworks, eventually starring in The Man Who Laughs, a film that inspired the character of the Joker in the Batman comics.

2. Theodore Roberts—a twinkly-eyed ham who made sinning look like so much fun in Cecil B. DeMille's sex comedies, yet he was equally convincing as the heavy in Joan the Woman and as Moses in The Ten Commandments. A stage actor who made his debut in 1880, he made 23 films with DeMille and appeared in 103 altogether.

1. Gustav von Seyffertitz—possibly the only actor to ever upstage the legendary Mary Pickford, his performance as the evil "baby farmer" in Sparrows ranks as one of the great fiends of the silent era. Mostly playing slippery, sly villains, he worked with everybody—DeMille, Barrymore, Garbo, Fairbanks, Valentino, Dietrich, von Sternberg, Marion Davies, Wallace Reid and, of course, Pickford—carving out a long career as the man you love to hate.

Tomorrow: My Favorite Character Actresses of the Silent Era.

Showing posts with label Ernest Torrence. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ernest Torrence. Show all posts

Saturday, November 9, 2013

What A Character Blogathon, Part One: My Favorite Character Actors Of The Silent Era

Saturday, January 7, 2012

The Katie-Bar-The-Door Awards Redux (1928-1929)

I've chosen a best picture in three different categories (drama, comedy/musical and foreign language) but make no mistake, The Passion of Joan of Arc is the best picture of the year. It's not only the most modern looking movie of the silent era, it's the most modern looking movie of any era, and its subject matter—torture, capital punishment, political corruption and religious fanaticism of every stripe—is probably more relevant today than when Dreyer made it.

I've chosen a best picture in three different categories (drama, comedy/musical and foreign language) but make no mistake, The Passion of Joan of Arc is the best picture of the year. It's not only the most modern looking movie of the silent era, it's the most modern looking movie of any era, and its subject matter—torture, capital punishment, political corruption and religious fanaticism of every stripe—is probably more relevant today than when Dreyer made it.Not to mention it's the most gripping courtroom drama ever made—better than Perry Mason, better than Law and Order, better than Witness for the Prosecution, Twelve Angry Men and A Few Good Men put together. It really is that good.

As for my choice of the year's best comedy, I'll grant you that Steamboat Bill, Jr. and The Cameraman are funnier. But Steamboat Willie had a much bigger impact. Not only did it give us Mickey Mouse, in practical terms, it gave us Walt Disney, too, because without this desperately needed hit, his fledgling studio would likely have gone under.

In any event, if The Simpsons can spoof it (as "Steamboat Itchy") without needing to explain the source, you know it is deeply embedded in the cultural conscience.

But Buster Keaton takes home the acting honors, as well he should. As thespians go, I'd stack him against a cartoon rodent any day.

PICTURE (Drama)

winner: The Wind (prod. Victor Sjöström)

nominees: Blackmail (prod. John Maxwell); The Docks Of New York (prod. J.G. Bachmann); The Iron Mask (prod. Douglas Fairbanks); The Wedding March (prod. Pat Powers and Erich von Stroheim)

Must-See Drama: Beggars Of Life; Blackmail; The Docks Of New York; The Iron Mask; Our Dancing Daughters; Piccadilly; The Wedding March; The Wind

PICTURE (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Steamboat Willie (prod. Walt Disney)

nominees: The Broadway Melody (prod. Irving Thalberg, Harry Rapf and Lawrence Weingarten); The Cameraman (prod. Buster Keaton); Show People (prod. Marion Davies and King Vidor); Steamboat Bill, Jr. (prod. Joseph M. Schenck);

Must-See Comedy/Musical: The Broadway Melody; The Cameraman; Show People; Steamboat Bill, Jr.; Steamboat Willie; Two Tars

PICTURE (Foreign Language)

winner: The Passion Of Joan Of Arc (prod. Société générale des films)

nominees: Un Chien Andalou (prod. Luis Buñuel); The Fall Of The House Of Usher (prod. Jean Epstein); Man With The Movie Camera (prod. VUFKU)

Must-See Foreign Language Pictures: Un Chien Andalou; The Fall Of The House Of Usher; Man With The Movie Camera; The Passion Of Joan Of Arc

ACTOR (Drama)

winner: George Bancroft (The Docks Of New York)

nominees: Warner Baxter (In Old Arizona); Douglas Fairbanks (The Iron Mask); John Gilbert (A Woman Of Affairs and Desert Nights); Erich von Stroheim (The Wedding March)

ACTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Buster Keaton (Steamboat Bill, Jr. and The Cameraman)

nominees: William Haines (Show People); Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy (Two Tars)

ACTRESS (Drama)

winner: Lillian Gish (The Wind)

nominees: Louise Brooks (Beggars Of Life); Betty Compson (The Docks Of New York); Maria Falconetti (The Passion Of Joan Of Arc); Greta Garbo (The Mysterious Lady, A Woman Of Affairs and Wild Orchids)

ACTRESS (Comedy/Musical)

winner: Marion Davies (Show People)

nominees: Bessie Love (The Broadway Melody)

DIRECTOR (Drama)

winner: Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion Of Joan Of Arc)

nominees: Victor Sjöström (The Wind); Josef von Sternberg (The Docks Of New York); Dziga Vertov (Man With The Movie Camera); Erich von Stroheim (The Wedding March)

DIRECTOR (Comedy/Musical)

winner:Luis Buñuel (Un Chien Andalou)

nominees: Ub Iwerks (Steamboat Willie); Edward Sedgwick (The Cameraman); King Vidor (Show People)

SUPPORTING ACTOR

winner: Ernest Torrence (Steamboat Bill, Jr. and Desert Nights)

nominees: Wallace Beery (Beggars Of Life); Donald Calthrop (Blackmail); Lewis Stone (A Woman Of Affairs); Gustav von Seyffertitz (The Mysterious Lady and The Docks Of New York)

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

winner: Anita Page (Our Dancing Daughters)

nominees: Olga Baclanova (The Docks Of New York); Mary Nolan (West Of Zanzibar); Zasu Pitts (The Wedding March); Anna May Wong (Piccadilly)

SCREENPLAY

winner: Frances Marion; from a novel by Dorothy Scarborough (The Wind)

nominees: Jules Furthman; story by John Monk Saunders; titles by Julian Johnson (The Docks Of New York); Joseph Delteil and Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion Of Joan Of Arc)

SPECIAL AWARDS

Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks (the creation and marketing of Mickey Mouse); Douglas Shearer (The Broadway Melody) (Special Achievement In The Use Of Sound); "The Broadway Melody" (The Broadway Melody) (Best Song); Un Chien Andalou (prod. Luis Buñuel) (Best Short Subject); John Arnold (The Wind) (Cinematography)

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

A Recap Of The Katie Award Winners For 1928-29, A List Of Must-See Movies And A Word About Erich von Stroheim

The last of the Katies for 1928-29 have been awarded—and it only took six weeks! At this rate, I'll reach the present day in, hmm, let's see, nine years.

The last of the Katies for 1928-29 have been awarded—and it only took six weeks! At this rate, I'll reach the present day in, hmm, let's see, nine years.Well, better get to it.

In case you've forgotten who won Katies for 1928-29, here's a recap of the year's winners:

Picture: The Passion of Joan of Arc (prod. Société générale des films)

Actor: Buster Keaton (Steamboat Bill, Jr.)

Actress: Lillian Gish (The Wind)

Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion of Joan of Arc)

Supporting Actor: Ernest Torrence (Steamboat Bill, Jr.)

Supporting Actress: Anita Page (Our Dancing Daughters)

Screenplay: Frances Marion (The Wind)

Special Award: Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks (the creation and marketing of Mickey Mouse); Steamboat Bill, Jr. (prod. Joseph M. Schenck) (Best Picture-Comedy); Erich von Stroheim (The Wedding March) (Best Actor-Drama); Marion Davies (Show People) (Best Actress-Comedy); Douglas Shearer (The Broadway Melody) (Special Achievement In The Use Of Sound); "The Broadway Melody" (The Broadway Melody) (Best Song); Un Chien Andalou (prod. Luis Buñuel) (Best Short Subject); John Arnold (The Wind) (Cinematography)

And because a list of awards doesn't tell the whole story, here's another list, this time my selections for the "must-see" movies of the year:

Must-See Movies Of 1928-29: The Cameraman; Un Chien Andalou; The Docks Of New York; The Iron Mask; Our Dancing Daughters; The Passion Of Joan Of Arc; Show People; Steamboat Bill, Jr.; Steamboat Willie; The Wedding March; The Wind

I've written about each of the listed Katie Award winners and in doing so I've also written about each of the must-see movies—except The Wedding March, the last movie directed by Erich von Stroheim that can be reasonably said to work. It's the story of a young aristocrat forced to marry for money rather than love. Von Stroheim was surprisingly sympathetic in the lead role, reminding you, as he would again in Sunset Boulevard, that he wasn't just a pretty face in a monocle. For his performance in The Wedding March, I nominated him for a Katie (he lost to Buster Keaton).

I've written about each of the listed Katie Award winners and in doing so I've also written about each of the must-see movies—except The Wedding March, the last movie directed by Erich von Stroheim that can be reasonably said to work. It's the story of a young aristocrat forced to marry for money rather than love. Von Stroheim was surprisingly sympathetic in the lead role, reminding you, as he would again in Sunset Boulevard, that he wasn't just a pretty face in a monocle. For his performance in The Wedding March, I nominated him for a Katie (he lost to Buster Keaton).Like most of his work (see, e.g., Greed and Queen Kelly), the version of The Wedding March that wound up on the screen was quite a bit less than what von Stroheim had envisioned. Most film buffs have heard tales of von Stroheim's nine (nine, Mrs. Bueller!) hour cut of Greed that the studio whittled down to 130 minutes. In this case, The Wedding March is only the first third of what von Stroheim, who was not one to learn a lesson, conceived of as a six-plus hour movie tracing the reluctant courtship and subsequent marriage of the young aristocrat and a rich industrialist's crippled daughter (Zasu Pitts). The studio shut down the production after nine months and ordered von Stroheim to split the film as conceived into three parts, with The Wedding March at two hours to be followed by its sequel, The Honeymoon, and an unnamed third film to complete the trilogy. The Honeymoon was started but apparently never completed; its elements were destroyed by fire in the 1950s.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, I suspect the studio's intervention, rather than destroying a work of art, may well have saved von Stroheim from himself.

In retro- spect, I think it's clear that von Stroheim was attempt- ing, with all these six and nine hour cuts of his movies, to invent the HBO miniseries. And he was absolutely right that there is artistic merit to taking time to tell a nine-hour story—I mean, think of The Sopranos reduced from a thirteen-hour season to a two-hour movie. Instead of having a deeply-layered, nuanced story, you would wind up with the same slam-bang surface-level gangster fluff that routinely shows up in the theaters, here for a disappointing opening weekend and then gone forever.

In retro- spect, I think it's clear that von Stroheim was attempt- ing, with all these six and nine hour cuts of his movies, to invent the HBO miniseries. And he was absolutely right that there is artistic merit to taking time to tell a nine-hour story—I mean, think of The Sopranos reduced from a thirteen-hour season to a two-hour movie. Instead of having a deeply-layered, nuanced story, you would wind up with the same slam-bang surface-level gangster fluff that routinely shows up in the theaters, here for a disappointing opening weekend and then gone forever.But unfortunately for von Stroheim, HBO and the miniseries hadn't been invented yet. Hell, they hadn't invented television yet. He was stuck with what he had, silent movies, a brevity-is-the-soul-of-wit medium. And while I support an artist's right to chase a vision no matter how impractical, there is no way von Stroheim could have expected in his wildest fantasies that an audience was going to sit still for nine hours while he threw shadows on a screen. In that context of the world he worked in, von Stroheim was not so much an artist pushing the edge as a gasbag who couldn't get to the point. (Or in his case, most likely a pompous poseur with a pathological need to prove himself superior to a public he regarded as rabble. But I digress.)

But let's say for the sake of argument that von Stroheim was a genius and further that some scientist somewhere is working on a time machine that would bring von Stroheim, contract and camera in hand, to the home offices of HBO. The fact is, he still couldn't make a miniseries for HBO because he'd insist on a $100 million budget. Need to film a scene in a nondescript San Francisco boarding house? Go to San Francisco! Have a desert scene in the screenplay? Move your entire company to the desert for months to shoot a scene that winds up looking like something shot on a Hollywood backlot. He was extravagant beyond all reason, insisting on a fidelity to realism that didn't translate to the screen. With the way he spent money, on what in the end were tiny little art films, he never had a hope of turning a profit. No wonder he drove people like Irving Thalberg nuts.

But let's say for the sake of argument that von Stroheim was a genius and further that some scientist somewhere is working on a time machine that would bring von Stroheim, contract and camera in hand, to the home offices of HBO. The fact is, he still couldn't make a miniseries for HBO because he'd insist on a $100 million budget. Need to film a scene in a nondescript San Francisco boarding house? Go to San Francisco! Have a desert scene in the screenplay? Move your entire company to the desert for months to shoot a scene that winds up looking like something shot on a Hollywood backlot. He was extravagant beyond all reason, insisting on a fidelity to realism that didn't translate to the screen. With the way he spent money, on what in the end were tiny little art films, he never had a hope of turning a profit. No wonder he drove people like Irving Thalberg nuts."What's that about?" Thalberg asked von Stroheim as they watched the rushes from the director's 1925 movie, The Merry Widow, referring to one of the odder scenes in a movie heavily censored before its release.

"That is a foot fetish," von Stroheim said.

"You, Von," replied Thalberg, "have a footage fetish."

In all fairness, I should point out that Cecil B. DeMille routinely spent more money than von Stroheim. But I also have to point out that DeMille routinely made more money than von Stroheim. And as nasty a notion as that is to an artist, when you're making pictures with somebody else's money, you have to create the possibility that the guy writing the check will turn a profit or he's soon going to stop writing those checks.

Which really brings me to the most important point, that what survives of von Stroheim's work really isn't that pretty. Von Stroheim's characters may have indulged a wide variety of fetishes—the panty sniffing of Queen Kelly, the foot fondling of The Merry Widow—but von Stroheim himself had a fetish for the grotesque, grotesque in the true sense of the word, "characterized by the fanciful," distorting "the natural into absurdity, ugliness or caricature." For all his blather about realism, von Stroheim was attracted to the fantastic, and the problem with a fetish is that it is inaccessible to anyone who doesn't share the fetish, a serious problem if you're looking for an audience of millions to defray the cost of your particular brand of lunacy.

Which really brings me to the most important point, that what survives of von Stroheim's work really isn't that pretty. Von Stroheim's characters may have indulged a wide variety of fetishes—the panty sniffing of Queen Kelly, the foot fondling of The Merry Widow—but von Stroheim himself had a fetish for the grotesque, grotesque in the true sense of the word, "characterized by the fanciful," distorting "the natural into absurdity, ugliness or caricature." For all his blather about realism, von Stroheim was attracted to the fantastic, and the problem with a fetish is that it is inaccessible to anyone who doesn't share the fetish, a serious problem if you're looking for an audience of millions to defray the cost of your particular brand of lunacy.I'm willing to concede that it's possible that the nine (nine!) hour version of, say, Greed was subtle and brilliant and absorbing (that is, if you didn't have to watch it in a single sitting). As I said, The Sopranos whittled down to two hours would never have had the same impact that the full series had. We'll never know.

But I think it's more likely that von Stroheim needed someone to rein him in, control his impulses, find the movie buried within the miles of footage. The director needed direction.

In any event, von Stroheim only directed nine movies (two of which he didn't finish; five others were heavily cut). His last movie, 1933's Hello, Sister, was mostly reshot after the studio fired von Stroheim. I think to a degree his reputation is based on a sense of what-might-have-been rather than on what-was, the romantic cliche of the great artist with the corporate boot on his neck; but I think based on the what-was I've seen, the-what-might-have-been is a bit overblown.

All of which is an appropriately long-winded way of saying that The Wedding March might be the best movie Erich von Stroheim ever accidentally made.

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

Best Actor Of 1928-29: Buster Keaton (Steamboat Bill, Jr.)

If I found the choice between Lillian Gish and Maria Falconetti for the best actress of 1928-29 nearly impossible to make, the choice for best actor is a no-brainer: Buster Keaton may well have been the best actor of the Silent Era and Steamboat Bill. Jr. rivals The General as the best movie of his career. I had this pick ready to go months ago when I started this blog and watching Keaton's movies again has only deepened my regard for this wonderful talent.

If I found the choice between Lillian Gish and Maria Falconetti for the best actress of 1928-29 nearly impossible to make, the choice for best actor is a no-brainer: Buster Keaton may well have been the best actor of the Silent Era and Steamboat Bill. Jr. rivals The General as the best movie of his career. I had this pick ready to go months ago when I started this blog and watching Keaton's movies again has only deepened my regard for this wonderful talent.Born Joseph Frank Keaton VI into a family of traveling vaudeville performers, legend has it he was dubbed "Buster" when escape artist Harry Houdini saw the infant Keaton take a fall down a flight of stairs and bounce up unharmed. Whether he was born with it, or developed it doing "knockabout" routines on stage with his father, if Keaton wasn't the most talented pratfall artist in movie history, I'd like to see the guy who survived long enough to be a better one. He did stunts that rivaled those of Douglas Fairbanks, and when he was done, he doubled for his co-stars and did their stunts, too.

"The secret," he once said, "is in landing limp and breaking the fall with a foot or a hand. It's a knack. I started so young that landing right is second nature with me. Several times I'd have been killed if I hadn't been able to land like a cat."

Keaton made the leap from stage to screen in 1917 after meeting Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle who invited Keaton to shoot a scene with him in an upcoming short, The Butcher Boy. The rotund, expressive Arbuckle and the slender, deadpan Keaton proved to be a highly-successful team, making more than a dozen films together before Keaton struck out on his own, directing himself in the classic short One Week, which was just last year included in the National Film Registry.

Soon after, Keaton formed his own production company, and in 1923 made his first feature-length film, Three Ages, beginning a run of classic comedies that included Our Hospitality, Sherlock Jr., The Navigator, The General, Steamboat Bill, Jr. and The Cameraman, a body of work that for pure laughs—no song, no dance, no sentimentality—surpasses even Charles Chaplin, the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. Which is saying something considering the number of Katie Awards I see in the future for each of those acts.

Soon after, Keaton formed his own production company, and in 1923 made his first feature-length film, Three Ages, beginning a run of classic comedies that included Our Hospitality, Sherlock Jr., The Navigator, The General, Steamboat Bill, Jr. and The Cameraman, a body of work that for pure laughs—no song, no dance, no sentimentality—surpasses even Charles Chaplin, the Marx Brothers and the Three Stooges. Which is saying something considering the number of Katie Awards I see in the future for each of those acts.Like Chaplin, Keaton in the Silent Era was virtually a one-man act, writing, producing, directing, editing and starring in all his movies. One difference between Keaton and Chaplin, however, was Keaton's very un-modern reluctance to take credit where credit was due, often as with Steamboat Bill, Jr., slapping names like Carl Harbaugh on movies that he had, in fact, written and directed himself. (Of Harbaugh, Keaton later said, "He didn't write nothing. He was one of the most useless men I ever had on the scenario department." When asked why Harbaugh then received sole credit for writing Steamboat Bill, Jr., Keaton said, "Well, we had to put somebody's name up that wrote 'em ...")

I'm afraid this reticence cost Keaton Katie nominations for writing and directing this year. Somehow, though, I suspect his reputation will survive.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. is a classic fish-out-of-water story, the reunion of a ukelele-playing, college-educated fop (Keaton) with his strapping, working class father (Katie winner Ernest Torrence). The son soon becomes a pawn in his father's battle with the town banker for control of the local riverboat trade. In the course of the seventy-minute story, Keaton contends with shipwrecks, hurricanes and an unreasoning prejudice against French berets to win over his father and get the girl.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. is a classic fish-out-of-water story, the reunion of a ukelele-playing, college-educated fop (Keaton) with his strapping, working class father (Katie winner Ernest Torrence). The son soon becomes a pawn in his father's battle with the town banker for control of the local riverboat trade. In the course of the seventy-minute story, Keaton contends with shipwrecks, hurricanes and an unreasoning prejudice against French berets to win over his father and get the girl.Keaton conjures up an endlessly inventive series of gags—involving hats, collisions, chewing tobacco, a baby stroller, a jailbreak, an umbrella on a windy day, and many more—mostly turning on his misfit persona, his odd-couple relationship with his dad and his cheerful determination to succeed despite a preternatural inability to understand what it takes to do so.

One of my favorite early bits centers on the father's effort to give his son a makeover. After two deft flicks of a barber's razor remove Keaton's pencil-thin moustache, the father marches his son into a hatters to replace Keaton's beret with something he deems more suitable for a steamboat captain's son.

Keaton tries on a number of hats, including his own trademark pork pie (which he immediately rejects) before settling on an overly-large Panama. He and his father step into the street, a gust of wind blows the new hat into the river, and when his father turns around, Keaton is again wearing that same silly beret. (The Three Stooges later recycled the scene to great effect for their 1936 short, 3 Dumb Clucks, with Curly Howard and a touring cap substituting for Keaton and the beret.)

Keaton tries on a number of hats, including his own trademark pork pie (which he immediately rejects) before settling on an overly-large Panama. He and his father step into the street, a gust of wind blows the new hat into the river, and when his father turns around, Keaton is again wearing that same silly beret. (The Three Stooges later recycled the scene to great effect for their 1936 short, 3 Dumb Clucks, with Curly Howard and a touring cap substituting for Keaton and the beret.)Keaton delivers all of these comic moments with the understated deadpan style that made him famous and earned him the nickname "The Great Stone Face."

"I developed the 'Stone Face' thing quite naturally," Keaton said later. "[E]ven as a small kid, I happened to be the type of comic that couldn't laugh at his own material. I soon learned at an awful early age that when I laughed the audience didn't. So, by the time I got into pictures, that was a natural way of working."

It's this understated approach to comedy coupled with an utter lack of sentimentality that makes Keaton seem so modern.

The most unfor- gettable sequence of Steam- boat Bill, Jr., maybe the most famous single sequence of Keaton's career, is the one where a cyclone blows a house over onto Keaton, who only misses being killed because he miraculously happens to be standing right where an open attic window allows him to pass right through.

The most unfor- gettable sequence of Steam- boat Bill, Jr., maybe the most famous single sequence of Keaton's career, is the one where a cyclone blows a house over onto Keaton, who only misses being killed because he miraculously happens to be standing right where an open attic window allows him to pass right through. "First I had them build the frame- work of this building and make sure that the hinges were all firm and solid," Keaton explained. "Then you lay this framework down on the ground, and build the window around me. We built the window so that I had a clearance of two inches on each shoulder, and the top missed my head by two inches and the bottom my heels by two inches. We mark the ground out and drive big nails where my two heels are going to be. Then you put that house back up in position while they finish building it."

"First I had them build the frame- work of this building and make sure that the hinges were all firm and solid," Keaton explained. "Then you lay this framework down on the ground, and build the window around me. We built the window so that I had a clearance of two inches on each shoulder, and the top missed my head by two inches and the bottom my heels by two inches. We mark the ground out and drive big nails where my two heels are going to be. Then you put that house back up in position while they finish building it." It was actually a gag he'd first used in the short One Week but in this case, not only were they dropping a finished wall (rather than an open frame) on top of him, they were doing it during a simulated cyclone using six wind machines that proved powerful enough to accidentally blow a truck into the Sacramento River.

It was actually a gag he'd first used in the short One Week but in this case, not only were they dropping a finished wall (rather than an open frame) on top of him, they were doing it during a simulated cyclone using six wind machines that proved powerful enough to accidentally blow a truck into the Sacramento River.Most of the crew walked off in the set in protest, certain the stunt would kill him. Keaton himself declined to practice the stunt first, saying he knew it would work. "You don't do those things twice."

This attitude was in keeping with Keaton's standing order to his cinema- tographer to keep the camera rolling until he said cut or was killed. But it also gave his stunts a realism that puts your heart in your throat even as you're laughing at the gags.

This attitude was in keeping with Keaton's standing order to his cinema- tographer to keep the camera rolling until he said cut or was killed. But it also gave his stunts a realism that puts your heart in your throat even as you're laughing at the gags.Keaton always dismissed talk of his greatness—"How can you be a genius in slapshoes?"—but there's no doubt in my mind, or anyone else's these days, that a genius is exactly what he was. Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert calls him simply "the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies."

Despite his legendary prowess as a stuntman, Keaton landed wrong when after the release of Steamboat Bill, Jr. he jumped from producing his own films to signing on as a contract player at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It was a move that pretty much wrecked his career.

"[T]hey were picking stories and material without consulting me," he said, "and I couldn't argue them out of it. They'd say, 'This is funny,' and I'd say, 'I don't think so.' They'd say, 'This'll be good.' I'd say, 'It stinks.' It didn't make any difference; we did it anyhow. I'd only argue about so far, and then let it go."

After a promising start at MGM with The Cameraman, which I have nominated for best picture, the studio forced Keaton into a series of second-rate productions. Always the perfectionist, Keaton drowned his frustrations in alcohol, a habit which soon became a problem in and of itself. Always an acquired taste, what little popularity Keaton had soon faded and MGM released him from his contract in 1934.

The same story, incidentally, played out for any number of directors and actors at more studios than just MGM. The money men who ran the studios didn't seem to grasp that sound movies were something other than just silent movies with a song and a little talking thrown in. Care was needed to create a new medium—talking pictures—that was the equal to what directors such as Keaton, Chaplin, F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang had created during the Silent Era. Care was something few producers were willing to invest.

The same story, incidentally, played out for any number of directors and actors at more studios than just MGM. The money men who ran the studios didn't seem to grasp that sound movies were something other than just silent movies with a song and a little talking thrown in. Care was needed to create a new medium—talking pictures—that was the equal to what directors such as Keaton, Chaplin, F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang had created during the Silent Era. Care was something few producers were willing to invest.Keaton continued to work after leaving MGM, most memorably in Chaplin's 1952 comedy Limelight, but he never again reached the heights he'd attained during the Silent Era. He did live long enough to see a revival of interest in his career and was directly involved in the restoration and re-release of his silent comedies. He was awarded an honorary Oscar in 1960 in recognition of "his unique talents which brought immortal comedies to the screen." His last movie appearance, a supporting role in A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum, was released eight months after his death in 1966.

A Personal Note: Many years ago, when video tape was expensive and DVDs were non-existent, Katie-Bar-The-Door bought me a box set of Buster Keaton movies for $75. That was back when we could still afford both Christmas presents and the mortgage. Adjusted for inflation, those $75 would now buy you all of General Motors with enough left over to pick up your neighbor's house at foreclosure.

"Did you ever watch those Buster Keaton movies?" she once asked me.

"Did you ever watch those Buster Keaton movies?" she once asked me.Yes. Yes, I did. But I can see on the horizon hundreds of movies I haven't. What have I been doing with my time?

By the way, if you're wondering where the quotes for this essay came from, many of them came from a book I ran across while I was on the road this last weekend, Buster Keaton Interviews, edited by Kevin M. Sweeney. I highly recommend it if you're at all interested in Keaton.

Sunday, June 7, 2009

Best Supporting Actor Of 1928-29, Part Two: And The Winner Is ...

[To read Part One of this essay, click here.]

In sifting through the most highly (and not so highly) regarded movies of 1928-29, two supporting performances jumped out at me, the immortal Wallace Beery in William A. Wellman's Beggars Of Life, and the not as well known (to a modern audience at least) but equally talented Ernest Torrence in Buster Keaton's classic comedy Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Beggars of Life is about a teenage girl (Louise Brooks in a per- formance that brought her to the attention of German director P.W. Pabst) who kills her stepfather in order to avoid being raped. Disguising herself as a young boy, she escapes with a passing vagrant (Richard Arlen, co-star of the first movie to win the Oscar for best picture, Wings) only to fall into the hands of Oklahoma Red (Beery), the ruthless leader of a "hobo jungle" who wants the girl for himself.

Beggars of Life is about a teenage girl (Louise Brooks in a per- formance that brought her to the attention of German director P.W. Pabst) who kills her stepfather in order to avoid being raped. Disguising herself as a young boy, she escapes with a passing vagrant (Richard Arlen, co-star of the first movie to win the Oscar for best picture, Wings) only to fall into the hands of Oklahoma Red (Beery), the ruthless leader of a "hobo jungle" who wants the girl for himself.

The story by novelist Jim Tully was based on his own experiences riding the rails during a period of unemployment and homelessness. Well before the Depression would acquaint much of this film's audience with the life they were seeing on screen, Tully hoped to demythologize poverty, showing, for example, the brutality of "hobo jungles" and the ruthless treatment of the poor at the hands of arbitrary authorities.

Wallace Beery makes his first appearance during the movie's second act, arriving at the camp singing and carrying a keg of beer on his shoulder (some prints have Beery's growling singing voice on the soundtrack of this otherwise silent movie, others do not). Even with the lovely Louise Brooks on screen, Beery is the one your eyes are drawn to.

This phenomenon, the supporting performance that makes you forget the rest of the movie, was typical of Beery's career. Admittedly, sometimes Beery could be a distraction, but here he breathes life into a story that had threatened to grind to a halt.

Beery discovers Brooks, who has disguised herself as a boy, is a fugitive with a $1000 bounty on her head. Beery helps her escape from the others and from the police, but whether it's an act of altruism or pure self-interest becomes the central question of the film.

Beery discovers Brooks, who has disguised herself as a boy, is a fugitive with a $1000 bounty on her head. Beery helps her escape from the others and from the police, but whether it's an act of altruism or pure self-interest becomes the central question of the film.

Co-star Louise Brooks was blunt in her criticism of the movie: "[William Wellman] directed the opening sequence with a sure, dramatic swiftness that the rest of the film lacked." But of Beery, Brooks said, "His Oklahoma Red is a little masterpiece."

She's right. Beery plays Oklahoma Red as complex man rather than as a stock villain and, in addition to watching a key early Brooks performance, watching his internal contradictions play out is the main reason to track down this film. It's probably his most overlooked performance in a career that included starring roles in Grand Hotel, Dinner At Eight, Treasure Island and Min And Bill, and Oscar nominations for The Big House and The Champ, the latter a winner for Beery in 1931.

But Brooks was also right about the film overall. The action is repetitive, the acting outside that of Beery and Brooks is amateurish and for a movie inspired by a desire to show what riding the rails was really like, its insights sometimes feel shallow and cliched.

The same year, Ernest Torrence turned in an equally good performance in a better movie, Buster Keaton's classic Steamboat Bill. Jr., and he's my choice for the best supporting actor of 1928-29.

If Buster Keaton was the Great Stoneface because his comedy came from his lack of expression, then Torrence just had a face like an outcropping of stone—granite cheekbones, a long, hard jaw, and a nose that hung so precipitously over his lower lip, it was a danger to anyone who sheltered underneath it.

If Buster Keaton was the Great Stoneface because his comedy came from his lack of expression, then Torrence just had a face like an outcropping of stone—granite cheekbones, a long, hard jaw, and a nose that hung so precipitously over his lower lip, it was a danger to anyone who sheltered underneath it.

That face and his imposing size (he was 6'4") made Torrence a natural villain in the Silent Era when filmmakers relied on visual shorthand to tell their stories, but he had surprising range and a fan of silent movies is probably aware of his roles as Peter in Cecil B. DeMille's King Of Kings, the opportunistic rabble-rouser Clopin in The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Captain Hook in 1924's Peter Pan and the unlikely but effective love interest in the Clara Bow romance Mantrap.

Here, he plays Steamboat Bill, father to Buster Keaton's college graduate, Willie, and Torrence is one mightily p.o.'ed Popeye who at any moment might pop you one with the fist at the end of his powerful forearm. He provides the perfect comic foil to Keaton who looks like he's never been mad at anything in his life.

The story is simple but the execution is brilliant. Steam- boat Bill's reign as the top steam ship captain of River Junction is threatened by the arrival of a newer, larger, more opulent steamboat bankrolled by Bill's rival in town, John James King. While trouble brews between the two men, Bill's long-lost son in the form of Buster Keaton shows up. Not only is his son Willie completely unsuitable to work on his father's boat, he's also in love with rival King's daughter.

The story is simple but the execution is brilliant. Steam- boat Bill's reign as the top steam ship captain of River Junction is threatened by the arrival of a newer, larger, more opulent steamboat bankrolled by Bill's rival in town, John James King. While trouble brews between the two men, Bill's long-lost son in the form of Buster Keaton shows up. Not only is his son Willie completely unsuitable to work on his father's boat, he's also in love with rival King's daughter.

Hilarity ensues. Seriously. This ranks with The General as the funniest movie Keaton ever made.

Director Charles Reisner (and an uncredited Keaton) play up the odd couple story to great effect, the gruff, working class father disappointed in his college-educated son who arrives in town with a ukelele, a beret and a pencil-thin moustache. It helps that Torrence was an inch shy of being a full foot taller than Keaton (who was 5'5") and has shoulders broader than Keaton is tall.

Torrence proved to be a perfect straight man for Keaton, whose understated brand of comedy needed something big to play against, whether it was a train and the Union army in The General or Torrence and a hurricane in Steamboat Bill, Jr. But typical of Torrence's work, he doesn't play the role of father as a one-note villain. Steamboat Bill is unlike his son and doesn't understand him, but Torrence also shows a patient and protective side that makes him a three-dimensional father rather than a one-dimensional ogre. This bit of nuance truly enhances the comedy, which as I said is as good as anything Keaton ever did, which means it's as good as anything anybody ever did.

Torrence proved to be a perfect straight man for Keaton, whose understated brand of comedy needed something big to play against, whether it was a train and the Union army in The General or Torrence and a hurricane in Steamboat Bill, Jr. But typical of Torrence's work, he doesn't play the role of father as a one-note villain. Steamboat Bill is unlike his son and doesn't understand him, but Torrence also shows a patient and protective side that makes him a three-dimensional father rather than a one-dimensional ogre. This bit of nuance truly enhances the comedy, which as I said is as good as anything Keaton ever did, which means it's as good as anything anybody ever did.

Despite its brilliance, Steamboat Bill, Jr. was not a success at the box office. Buster Keaton was always an acquired taste and by 1928, audiences had tired of him even as he was reaching his peak.

Torrence's career didn't suffer from the commercial disappointment though. He successfully negotiated the leap to sound movies and made nineteen more films before dying suddenly in 1933 of complications after surgery for gall stones. He was only fifty-four.

In sifting through the most highly (and not so highly) regarded movies of 1928-29, two supporting performances jumped out at me, the immortal Wallace Beery in William A. Wellman's Beggars Of Life, and the not as well known (to a modern audience at least) but equally talented Ernest Torrence in Buster Keaton's classic comedy Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Beggars of Life is about a teenage girl (Louise Brooks in a per- formance that brought her to the attention of German director P.W. Pabst) who kills her stepfather in order to avoid being raped. Disguising herself as a young boy, she escapes with a passing vagrant (Richard Arlen, co-star of the first movie to win the Oscar for best picture, Wings) only to fall into the hands of Oklahoma Red (Beery), the ruthless leader of a "hobo jungle" who wants the girl for himself.

Beggars of Life is about a teenage girl (Louise Brooks in a per- formance that brought her to the attention of German director P.W. Pabst) who kills her stepfather in order to avoid being raped. Disguising herself as a young boy, she escapes with a passing vagrant (Richard Arlen, co-star of the first movie to win the Oscar for best picture, Wings) only to fall into the hands of Oklahoma Red (Beery), the ruthless leader of a "hobo jungle" who wants the girl for himself.The story by novelist Jim Tully was based on his own experiences riding the rails during a period of unemployment and homelessness. Well before the Depression would acquaint much of this film's audience with the life they were seeing on screen, Tully hoped to demythologize poverty, showing, for example, the brutality of "hobo jungles" and the ruthless treatment of the poor at the hands of arbitrary authorities.

Wallace Beery makes his first appearance during the movie's second act, arriving at the camp singing and carrying a keg of beer on his shoulder (some prints have Beery's growling singing voice on the soundtrack of this otherwise silent movie, others do not). Even with the lovely Louise Brooks on screen, Beery is the one your eyes are drawn to.

This phenomenon, the supporting performance that makes you forget the rest of the movie, was typical of Beery's career. Admittedly, sometimes Beery could be a distraction, but here he breathes life into a story that had threatened to grind to a halt.

Beery discovers Brooks, who has disguised herself as a boy, is a fugitive with a $1000 bounty on her head. Beery helps her escape from the others and from the police, but whether it's an act of altruism or pure self-interest becomes the central question of the film.

Beery discovers Brooks, who has disguised herself as a boy, is a fugitive with a $1000 bounty on her head. Beery helps her escape from the others and from the police, but whether it's an act of altruism or pure self-interest becomes the central question of the film.Co-star Louise Brooks was blunt in her criticism of the movie: "[William Wellman] directed the opening sequence with a sure, dramatic swiftness that the rest of the film lacked." But of Beery, Brooks said, "His Oklahoma Red is a little masterpiece."

She's right. Beery plays Oklahoma Red as complex man rather than as a stock villain and, in addition to watching a key early Brooks performance, watching his internal contradictions play out is the main reason to track down this film. It's probably his most overlooked performance in a career that included starring roles in Grand Hotel, Dinner At Eight, Treasure Island and Min And Bill, and Oscar nominations for The Big House and The Champ, the latter a winner for Beery in 1931.

But Brooks was also right about the film overall. The action is repetitive, the acting outside that of Beery and Brooks is amateurish and for a movie inspired by a desire to show what riding the rails was really like, its insights sometimes feel shallow and cliched.

The same year, Ernest Torrence turned in an equally good performance in a better movie, Buster Keaton's classic Steamboat Bill. Jr., and he's my choice for the best supporting actor of 1928-29.

If Buster Keaton was the Great Stoneface because his comedy came from his lack of expression, then Torrence just had a face like an outcropping of stone—granite cheekbones, a long, hard jaw, and a nose that hung so precipitously over his lower lip, it was a danger to anyone who sheltered underneath it.

If Buster Keaton was the Great Stoneface because his comedy came from his lack of expression, then Torrence just had a face like an outcropping of stone—granite cheekbones, a long, hard jaw, and a nose that hung so precipitously over his lower lip, it was a danger to anyone who sheltered underneath it.That face and his imposing size (he was 6'4") made Torrence a natural villain in the Silent Era when filmmakers relied on visual shorthand to tell their stories, but he had surprising range and a fan of silent movies is probably aware of his roles as Peter in Cecil B. DeMille's King Of Kings, the opportunistic rabble-rouser Clopin in The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Captain Hook in 1924's Peter Pan and the unlikely but effective love interest in the Clara Bow romance Mantrap.

Here, he plays Steamboat Bill, father to Buster Keaton's college graduate, Willie, and Torrence is one mightily p.o.'ed Popeye who at any moment might pop you one with the fist at the end of his powerful forearm. He provides the perfect comic foil to Keaton who looks like he's never been mad at anything in his life.

The story is simple but the execution is brilliant. Steam- boat Bill's reign as the top steam ship captain of River Junction is threatened by the arrival of a newer, larger, more opulent steamboat bankrolled by Bill's rival in town, John James King. While trouble brews between the two men, Bill's long-lost son in the form of Buster Keaton shows up. Not only is his son Willie completely unsuitable to work on his father's boat, he's also in love with rival King's daughter.

The story is simple but the execution is brilliant. Steam- boat Bill's reign as the top steam ship captain of River Junction is threatened by the arrival of a newer, larger, more opulent steamboat bankrolled by Bill's rival in town, John James King. While trouble brews between the two men, Bill's long-lost son in the form of Buster Keaton shows up. Not only is his son Willie completely unsuitable to work on his father's boat, he's also in love with rival King's daughter.Hilarity ensues. Seriously. This ranks with The General as the funniest movie Keaton ever made.

Director Charles Reisner (and an uncredited Keaton) play up the odd couple story to great effect, the gruff, working class father disappointed in his college-educated son who arrives in town with a ukelele, a beret and a pencil-thin moustache. It helps that Torrence was an inch shy of being a full foot taller than Keaton (who was 5'5") and has shoulders broader than Keaton is tall.

Torrence proved to be a perfect straight man for Keaton, whose understated brand of comedy needed something big to play against, whether it was a train and the Union army in The General or Torrence and a hurricane in Steamboat Bill, Jr. But typical of Torrence's work, he doesn't play the role of father as a one-note villain. Steamboat Bill is unlike his son and doesn't understand him, but Torrence also shows a patient and protective side that makes him a three-dimensional father rather than a one-dimensional ogre. This bit of nuance truly enhances the comedy, which as I said is as good as anything Keaton ever did, which means it's as good as anything anybody ever did.

Torrence proved to be a perfect straight man for Keaton, whose understated brand of comedy needed something big to play against, whether it was a train and the Union army in The General or Torrence and a hurricane in Steamboat Bill, Jr. But typical of Torrence's work, he doesn't play the role of father as a one-note villain. Steamboat Bill is unlike his son and doesn't understand him, but Torrence also shows a patient and protective side that makes him a three-dimensional father rather than a one-dimensional ogre. This bit of nuance truly enhances the comedy, which as I said is as good as anything Keaton ever did, which means it's as good as anything anybody ever did.Despite its brilliance, Steamboat Bill, Jr. was not a success at the box office. Buster Keaton was always an acquired taste and by 1928, audiences had tired of him even as he was reaching his peak.

Torrence's career didn't suffer from the commercial disappointment though. He successfully negotiated the leap to sound movies and made nineteen more films before dying suddenly in 1933 of complications after surgery for gall stones. He was only fifty-four.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

Best Supporting Actor Of 1928-29, Part One: The Nominees And The Problem Of Film Preservation

It's quite possible that the best sup- porting per- formance of the year was turned in not by my choice (who I will not reveal just yet) but by Lewis Stone, remembered now mostly for his recurring role as Judge Hardy in the Andy Hardy movie series (or perhaps for speaking the famous final line of Grand Hotel: "People come, people go. Nothing ever happens.").

It's quite possible that the best sup- porting per- formance of the year was turned in not by my choice (who I will not reveal just yet) but by Lewis Stone, remembered now mostly for his recurring role as Judge Hardy in the Andy Hardy movie series (or perhaps for speaking the famous final line of Grand Hotel: "People come, people go. Nothing ever happens.").But Stone was also a very fine character actor and he received his only Oscar nomination in 1928-29 for his performance in the Ernst Lubitsch movie The Patriot. For contemporary accounts, Stone's role was probably more of a supporting one (the Oscars didn't distinguish between lead and supporting performances back then) and if it's as good as people eighty years ago thought it was, he'd be a very good choice for the Katie Award for best supporting actor.

Unfortunately, like many silent films, The Patriot long ago vanished, leaving only a few fragments and it's impossible to tell from the trailer I've posted here, which focuses on the lead actor, Emil Jannings, what Lewis Stone did that so enchanted audiences and critics alike.

Jannings, as you may recall, won the first Oscar for acting but in this trailer at least, he serves up more ham in three minutes than you'd find in one of those two pound sandwiches at the Carnegie Deli. As for Stone, except for a single mention, the trailer ignores him completely.

And while you might be okay with giving an award for a performance you have never and will never see, Katie-Bar-The-Door doesn't put up with that sort of nonsense and I answer to her, not to you. So I had to pass on Stone and The Patriot.

I gave serious thought to shoe-horning Lewis Stone into the award for his supporting performance in A Woman Of Affairs, the third movie pairing of Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, and the first of seven movies Stone made with Garbo. Stone was quite good in the thankless role of the family doctor and friend who stands around being wise while everyone behaves like a jackass, good enough to earn at least a nomination.

But in the end, the preposterous nature of the story, about a woman who destroys herself and everyone around her to protect the reputation of a man hardly worth protecting, undermines Stone's effort, leaving him hanging, as they say, like an elephant on a clothesline.

But in the end, the preposterous nature of the story, about a woman who destroys herself and everyone around her to protect the reputation of a man hardly worth protecting, undermines Stone's effort, leaving him hanging, as they say, like an elephant on a clothesline.Stone starred in another Garbo movie in 1929, Wild Orchids, in which he plays a cuckolded husband who gets his revenge while on a tiger hunt with a Javanese prince. The New York Times called his performance "splendid," others have called it "solid," but quite frankly the story is even dumber than the one in A Woman Of Affairs (and I like Garbo). So a nomination for Stone, admiration for a long career that covered nearly forty years and a hundred and fifty movies, but no Katie.

Also missing in action, thanks to Hollywood's shoddy treatment of its own past, is Reginald Owen in The Letter. Readers of my generation may remember Owen best as Admiral Boom in 1964's Mary Poppins, but he was also a hard-working character actor and always worth a look come award time. Unfortunately, as I will discuss at greater length when I write about the brief life of Oscar-nominee Jeanne Eagels, The Letter is partially lost and what is left sits in a film archive, unavailable for viewing except for rare exhibitions—which is my way of saying I haven't seen it and am not likely to anytime soon.

Another possible nominee was veteran character actor Gustav von Seyffertitz for his role in Greta Garbo's The Mysterious Lady, but in the end his sole mode of acting, a holdover I suppose from the Silent Era, is to glower. He juts out his long, granite chin, beetles his eyebrows and glowers angrily. And then when watching other von Seyffertitz performances, I began to realize he glowers a lot. Like all the time. He was Hollywood's go-to guy for glowering. You want to hand out an award for glowering, von Seyffertitz was your man (okay, I like the word "glower"), but you want an actor with a bit of range, you look elsewhere.

Another possible nominee was veteran character actor Gustav von Seyffertitz for his role in Greta Garbo's The Mysterious Lady, but in the end his sole mode of acting, a holdover I suppose from the Silent Era, is to glower. He juts out his long, granite chin, beetles his eyebrows and glowers angrily. And then when watching other von Seyffertitz performances, I began to realize he glowers a lot. Like all the time. He was Hollywood's go-to guy for glowering. You want to hand out an award for glowering, von Seyffertitz was your man (okay, I like the word "glower"), but you want an actor with a bit of range, you look elsewhere.I also considered Donald Calthrop who plays a twitchy little weasel in the first Alfred Hitchcock talkie, Blackmail. He's pretty good in it, but overall, it's not one of Hitchcock's better efforts and given that Hitchcock and his oeuvre will wind up being well-represented during the course of this blog, I didn't see any need to make more of Calthrop's performance than it deserves.

Which to my mind leaves two major contenders for the prize of best supporting actor of 1928-29, Ernest Torrence in Buster Keaton's comedy classic, Steamboat Bill Jr., and Wallace Beery in the movie that vaulted Louise Brooks to the first rank of American silent actresses, Beggars Of Life.

I'll talk about both of them in my next post and then bless one of them with a coveted Katie.

[To continue to Part Two, click here.]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)